Drake Wants to Stretch Your Mind Like a Canvas

In August, a war of words broke out between Meek Mill, a rapper best known as Nicki Minaj’s boyfriend, and Drake, the superstar hip-hop artist, whose If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late was the first album to sell a million copies this year. On Twitter, Mill accused Drake of having used a ghostwriter for a song they had worked on together. Drake, who is an unorthodox rapper—he doesn’t just rhyme, he sings; he’s melodic, confessional, and romantic, as well as militant—responded to the charges with a brilliant, manifesto-like retort. Instead of lobbing equally incendiary tweets, Drake rose above the feud, saying, “I signed up for greatness. This comes with it.”

That higher calling/larger ambition has been a theme throughout Drake’s life. Born Aubrey Drake Graham to a biracial couple in Toronto, the musician, 29, has been performing since childhood. At 14, he landed a role on Degrassi: The Next Generation, the long-running, hugely popular, emotionally complicated Canadian teen soap opera. At the same time, Drake was already making music. “That was part of the reason I was kicked off the show,” Drake told me, calling from Los Angeles in late summer. He was there recording his next album, Views From the 6, and would be performing the next night in Las Vegas. (A surprise album, What a Time to Be Alive, recorded with fellow rapper Future, dropped September 20 and immediately went to No. 1 on iTunes.) “Back then, I’d spend a full day on set and then go to the studio to make music until 4 or 5 a.m. I’d sleep in my dressing room and then be in front of the cameras again by 9 a.m. Eventually, they realized I was juggling two professions and told me I had to choose.” Drake laughed. “I chose this life.”

Although Drake burst onto the scene as a unique musical force, he remained a kind of multi-hyphenate: In 2014 he hosted the ESPY awards and Saturday Night Live, and was sharp and funny on both. “I can’t wait to get back into acting,” Drake told me. “No one ever asks me to do movies, and, although music is my focal point now, I’d love to do a film. That was the life that I lived before, and it would be interesting to live it again.” Recently, Drake has become involved with the art world: He was commissioned by Sotheby’s, in New York, to create a soundtrack for an exhibition and private sale of works by important African-American artists, including Theaster Gates, Wangechi Mutu, David Hammons, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, at the auction house. “The art at Sotheby’s moved me like a song would,” Drake said. “I saw music in those paintings. I now try to treat each single as a piece of art. I try to attach the sound that I’m making to an image in my mind.”

Lynn Hirschberg: What was it like being a muse for this project for W?

Drake: It’s the first time I’ve ever been a “muse,” but I’m used to collaborating. Curiosity is the best part of working with any kind of artist. You want to see how somebody else’s process works. It’s like learning a secret. My mother was a teacher, and she brought all kinds of things into our house. So I learned early on that inspiration could come in many forms, from many people.

Were you raised around art?

We didn’t really have paintings on the walls, but I grew up with album covers! I loved the Marvin Gaye cover for What’s Going On. It made me want to hear the music, to be in that world. I liked anything visual that pulled me into the music.

You still live in Toronto. Most people leave…

Really? Most people I know stay in Toronto. I plan to spend the rest of my life there. The talk, the smell, the sound that comes out of that city is home to me. When I think about the girls I want to get romantic with, it’s a girl from Toronto who knows what I’m talking about when we drive around the city.

When you wrote, “I signed up for greatness,” what exactly did you mean?

Realizing that I had a larger purpose was one of the most comforting, peaceful feelings. With music, especially, I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m a vessel to deliver emotion to people. I want to provide the background music to your life as you live it. I’m there for you in heartbreak and tragedy and joy. The thought of being remembered is what keeps me going. What I was trying to say is, the negatives don’t matter—it’s history that counts. At 19, I was just really, really excited to be in the room. Everything was romantic then. Now, nearly a decade later, it’s a bit different. I have to speak against negativity and conflict. There’s so much bullshit that you’re forced to address, but it’s okay. I’m afraid I sound boosie.

What does “boosie” mean?

It’s a Toronto word. It means “talking that talk.” So, I should stop being boosie…let’s go back to art!

Okay! Do you sing in the shower?

I don’t really sing, but I do practice answers to questions in the shower. I talk to myself. I use my shower time to figure out how to respond to the world.

Water is an antidote to the pressures of your life.

Actually, I love pressure! I’m always thinking, How do I top what I’ve done? How do I make this thing stronger? I ask myself, “Why does Adele’s album go diamond, and how do I do that? How do I create art that makes minds stretch further?” I want to give many, many people many, many moments before I’m gone. That’s truly the art of what I do. It’s the only goal.

Drake: View From the Five

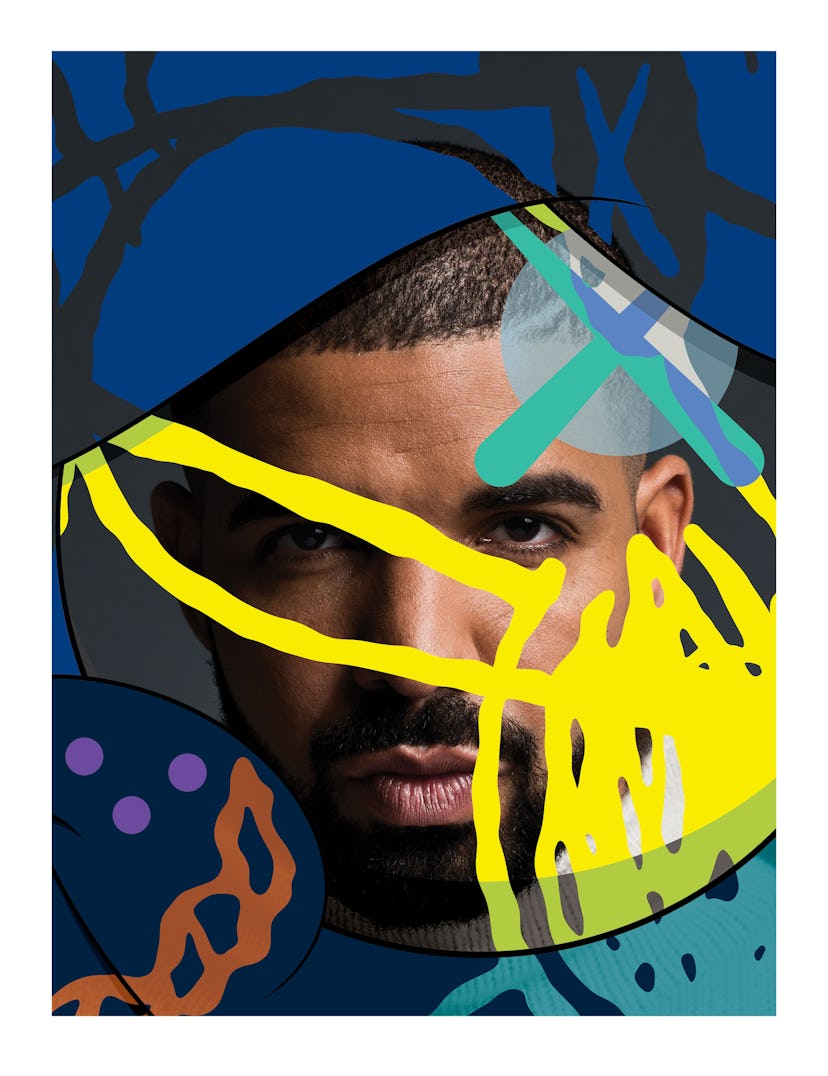

Drake, by KAWS. Photographed by Caitlin Cronenberg. Drake wears the Elder Statesman sweater.

JIM JOE The mysterious Canadian-born artist known only as JIM JOE has built a persona on anonymity. Refusing to reveal his/her gender, biography, or identity, JIM JOE gives interviews only by e-mail and sends riddle-me-this replies spelled out in all capital letters—the same format the artist uses for his/her moniker on Twitter and in images the artist posts on his/her website. JIM JOE first came on the scene around 2010, when his/her distinctive chicken-scratch graffiti and gnomic phrases began appearing in chalk, marker, and spray paint on Dumpsters, fire hydrants, and buildings all over downtown New York. The artist has shown paintings and installations at galleries in New York (the Hole) and Toronto (Cooper Cole) but is best known for the artwork that covered Drake’s surprise 2015 “mix-tape” album, If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late. JIM JOE’s sloppy, slanted handwriting went viral, launching countless memes spoofing it, as well as a website that allows visitors to make their own Drake album cover using a look-alike jim joe font and style. “A tumbleweed connector,” as the artist Mark Flood calls his friend, JIM JOE has also worked as a visual advisor to Kanye West, creating the sketch of West wearing a mask for his Yeezus iTunes page. When asked about the work So I Shot Myself, at left, JIM JOE, who photographed Drake in Toronto the day after the rapper Meek Mill launched his feud with Drake on Twitter, replied: THE ATTACHED WORK WAS DONE IN AN AIR-CONDITIONED ROOM WITH A FAN. THE TEXT WAS INSPIRED BY A LADY WHO YAWNED ON THE SUBWAY AND THEN EVERYBODY FOLLOWED SUIT. THE STORY WAS INVERTED AND NOW EXISTS AS A DARKER POEM THAT CASTS A SHADOW OVER DRAKES LARGE GRIN. IT IS EQUAL PARTS ENGAGEMENT AND IRREVERENCE. CRY NOW AND LAUGH LATER. THERE IS SOME HUMOR IN THERE TOO.

So I shot myself, by JIM JOE.

KAWS The art world’s most visible populist, the artist Brian Donnelly, who is known as kaws, has long mined mass consumer culture and its proliferating platforms for his own ends. Taking a page from his teen-hood hero, the Pop artist Keith Haring, kaws works inside, outside, and well beyond the white cube, seeing art object and product, museum, shop, and street as part of his creative universe. In his hands, iconic cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse and the Michelin Man are reimagined as Everymen you’re as likely to find in the form of a vinyl toy or a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloon as you are to see in a gallery or museum. Meanwhile, his paintings, such as the cover image for this issue, nod to the zonked-out style of Peter Saul, with their exploding neon palette and graphic punch. The 40-year-old New Jersey native got his start in the ’90s as a graffiti artist, tagging trains and billboards. After studying at New York’s School of Visual Arts, he began lifting ads from bus shelters, painting in figures, and then putting them back where he found them. In Japan in the late ’90s, eager to see his work in 3-D, he collaborated with the company Bounty Hunter to produce his first collectible toy: a gray vinyl Mickey Mouse figure with x-ed-out eyes who looks as if he’s in the throes of an existential crisis. (Companion, as he’s known, has been a recurring character in KAWS’s work.) Later on, KAWS designed streetwear for the hip brand a Bathing Ape. These days, with a résumé that includes a Kanye West album cover, commissions from Pharrell Williams, and a growing fan base of blue-chip collectors and museums, the shy, unassuming artist creates monumental sculptures in bronze and wood that he hopes “feel and look like the toys I started out making.” His project for W plays with that shifting scale: KAWS placed tiny 3-D-printed action figures of Drake at the bulbous feet of prototype models for his gigantic “Companion” sculptures. (The double figure at far right is a model for Along the Way, an 18-foot-tall work currently at the Brooklyn Museum.) KAWS arranged and photographed the tableau atop a wooden shipping crate in his Williamsburg studio; the Drake figurine’s poses, he says, were inspired by the selfies he’s seen on social media of visitors interacting with his sculptures in public spaces. “I’ve always been interested in different ways of reaching an audience,” says the artist, whose paintings and sculptures will be on view at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, in England, in February 2016, and will be followed by a retrospective at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, in Texas, next fall. “You go into a museum and the gift shop is full of products made around dead artists’ stuff, and usually it’s pretty badly done,” he observes. “And I just think, I want to do that while I’m alive, so if my stuff gets reproduced, it’ll be good.”

Artwork by KAWS; special thanks: Gentle Giant and 3D Imaging.

Mark Flood For much of his career, the Houston artist Mark Flood, 58, has taken swipes at the art establishment. When he was a musician in the underground ’80s punk band Culturcide, he also made provocative paintings and collages that critiqued media brainwashing. Around that time, when a painting of his that read eat human flesh ended up in the custody of the Houston police following a drug raid, the burst of notoriety spurred Flood to sell ad space on his canvases. Flood shot to art world prominence in 2000 with his “Lace” paintings—colorful acrylic pieces richly patterned with traces of torn fabric—but before that, he had barely sold any work. His day jobs, however, provided plenty of source material for his art. When he was an assistant in the records department at Texaco, he says, he would spend all day delving into files on industrial literature and advertising and making collages at his desk. At Houston’s Menil Collection, where he was an exhibitions assistant for 18 years, he made miniatures of artworks for the museum’s scale model, which the curators would use to plan shows. Flood’s current exhibition at Stuart Shave/Modern Art gallery, in London, through November 14, introduces his “Rothko Derivatives,” computer-generated paintings inspired by the Mark Rothko canvases Flood saw daily at the Menil. In 2016, a survey of the past 15 years of Flood’s raucous output opens at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. Over the years, Flood has made collages dealing with celebrity culture, reassembling iconic images to absurd effect. This assignment allowed him to explore the nature of a famous face firsthand. “I said to Drake, ‘I want to see how much we can put in shadow or distort and still have it be you.’ ” Flood snapped Drake through a lattice of fabrics in an effort to obscure him. “What’s intriguing to me about our obsession with celebrity is how ancient it is,” Flood says. “Whether it’s Zeus staring at you from a Greek temple 2,000 years ago or Drake gazing at you from the cover of a magazine, there’s this continuity in our hunger for images of people who stare back at us.”

Artwork by Mark Flood; Photography assistant: Ryan Morris.

Henry Taylor Henry Taylor didn’t sell his first portrait until he was well into his 40s. A late starter, he spent a decade working the night shift as a psychiatric technician in a California state hospital and took painting classes by day. His first subjects were the patients he tended to. “They would act out, and I’d paint them while they were in restraints, since they couldn’t go anywhere,” says the Los Angeles artist, who graduated from the California Institute of the Arts in 1995 and had his breakthrough show in 2007 at the Studio Museum in Harlem. All along, he has painted whoever is around: his cousin, a guy who slept on his porch, a 60-year-old female crack addict he met on the street. But his cast also includes those he considers members of his wider community, whether it’s the Olympic jumper Carl Lewis or Sean Bell, the unarmed black man who was shot 50 times by police in Queens in 2006. Taylor, 57, paints quickly and exuberantly, usually on canvas but also on cereal boxes, suitcases, and cigarette packs. Recently, he began making a short film about his grandfather, who kept horses in East Texas during the Depression and was shot and killed during a robbery. The first time Taylor heard Drake’s 2013 song about his early years, “Started From the Bottom,” he recalls thinking, “That’s the story of my life. I, too, tell a story in my paintings.” The youngest of a brood of eight, Taylor, like Drake, was raised by a single mother. As a kid, he dabbled in poetry. “Growing up, you didn’t let everybody know your aspirations, because maybe they weren’t considered cool,” he says. For his W commission, Taylor talked to Drake on FaceTime and grabbed a few screen shots. Several days later, Taylor was looking at some pictures he’d taken while driving in Marfa, Texas. He was struck by one, in particular, of the landscape above his dashboard. “There it is: 0 to 100,” he remembers thinking, referencing Drake’s 2014 track about his bid for the hip-hop throne. “I’m putting that in there.” Another lyric, “Wrist bling, got a condo up in Biscayne,” from Drake’s 2011 “The Motto” led Taylor to place his subject on Miami’s Biscayne Boulevard. “I played the songs and tried to make something that he might look at and say, ‘Yeah, you know, that motherfucker is listening to my shit. He’s paying attention.’ ”

Artwork by Henry Taylor.

Katherine Bernhardt Katherine Bernhardt’s wildly dynamic paintings reflect her ever-changing obsessions. She started out making Expressionist portraits of the fashion models she was transfixed by as a teen, dashed off with slashing strokes in lurid colors. A trip to Morocco in 2008 sparked her love of that country’s rugs and inspired canvases full of riotous abstract patterns and forms. (With her Moroccan-born second husband, Youssef Jdia, she cofounded Magic Flying Carpets in 2009, a website and pop-up that sells rugs to support the traditions of Morocco’s Berber women.) Next came commonplace consumer items like bananas, hamburgers, and basketballs set against saturated backdrops. And, lately, the tropical lushness of Caribbean life has her spellbound. “I’ve made about 10 trips to Puerto Rico; I want to move to San Juan,” says Bernhardt, 40, who was born in St. Louis and works out of a studio in Flatbush, Brooklyn. Not surprisingly, her fall show at Venus Over Manhattan gallery in New York “was all about Puerto Rico. So there are sharks, sea turtles, plantains, and papayas.” The graffitied wall in this photograph of Drake, taken at her behest in front of a West Indian variety store in Toronto, references Fruit Salad, her eye-popping mural on the facade of Venus Over Manhattan’s recently opened Los Angeles outpost. (Her first public work, it’s become something of a hit on Instagram, with its hodgepodge of color-block watermelons, toucans, and cigarettes.) When Bernhardt learned that Drake wanted to be photographed in his hometown of Toronto, she immediately thought of her Guyanese-born first husband, who also lived in that city. As a couple, she recalls, they spent a lot of time in Toronto’s West Indian neighborhood: The patterns and colors of its markets had just the kind of wallpapered backdrop she wanted for her depiction of Drake. Other works of this kind are surely in Bernhardt’s future—she says that as a result of Fruit Salad, she’s now entertaining more offers than she can accommodate to paint murals all over the country. “I get to pick what I want to do,” she says in disbelief. “My dream is to paint Cafetería Mallorca in Old San Juan. Now that would the ultimate.”

Artwork by Katherine Bernhardt: photograph by Caitlin Cronenberg; digital technician: Al Quintero; photography assistant: Jeffrey Glaab; painting by Katherine Bernhardt.

A portrait of Drake by Katherine Bernhardt.

A portrait of Drake by JIM JOE.

A portrait of Drake by Mark Flood.