Don Bachardy: The Stars in His Eyes

The famed portraitist—and longtime companion of the late writer Christopher Isherwood— has captured all of Tinseltown, past and present.

In the mornings, Don Bachardy rises with the sun. He reads quietly until half past noon, when he puts his book down and, like he’s done nearly every day for five decades, picks up a paintbrush. “Working makes me feel good; it’s what keeps me going,” Bachardy tells me one day in December. At a glance, it can seem as if most of Hollywood—present and past, from writers to directors to stars—has sat for the 80-year-old Los Angeles–born portrait artist, who is calling from his house nestled in Santa Monica Canyon, where he’s lived and worked since 1962. For many years, he resided there with his older companion, the famed English writer Christopher Isherwood. Until Isherwood’s death in 1986, Chris and Don, as they were known, were considered gay royalty; Isherwood’s 1964 novel, A Single Man, inspired by an especially fraught period of their often tumultuous relationship, is a foundational text of modern gay literature. (Tom Ford made it into a film in 2009.)

When they first met at a local beach, Bachardy was 18, with a goofy, toothy smile that made him seem even younger. Isherwood was 48 and accomplished. By then he had already published The Berlin Stories, upon which Cabaret was later based and which includes his famous declaration: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.”

“We were both recorders by nature,” Bachardy explains. (Their gossipy, deliciously bitchy correspondence was published last year as The Animals: Love Letters Between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy.) He credits Isherwood with encouraging and shaping his instinct for capturing faces, which he claims he first applied to paper, in crayon, at age 3 or 4. “Chris knew exactly what to do with me,” Bachardy says in the 2008 documentary Chris & Don: A Love Story. “His role could be described as that of the art villain. He took this young boy, and he warped him to his mold…” At the time, Bachardy was infinitely malleable. A year into their romance, he’d even acquired Isherwood’s mannerisms and a vaguely British accent, which he retains to this day. “I couldn’t help it,” he says in the film. “I’m an unconscious impersonator.”

When Bachardy was young, his mother impressed upon him the glamour of the movies. “I decided that if I couldn’t be an actor—and by that I meant a movie star—I would be a failure,” he recalls. “But I found something better. I get all the pleasure of interpretation in my sittings; I’m acting the role of the person I’m looking at.” Because Isherwood, like F. Scott Fitzgerald before him, arrived in Hollywood to ply his trade as an already celebrated writer, he kept company with the likes of Montgomery Clift, Ginger Rogers, Laurence Olivier, Bette Davis, Fred Astaire—all of whom would eventually pose for his protégé. Bachardy’s portraits of the industry’s luminaries are collected in two books, 2000’s Stars in My Eyes and 2014’s Hollywood. (An exhibition of work from the latter will be on view January 24 through February 28 at Craig Krull Gallery, in Santa Monica.) I ask him if he feels he’s met young Don’s ambitions. “Oh, I’ve gone further,” he says firmly.

Perhaps because he was always trying to catch up to his illustrious partner (and Isherwood’s famous friends, who could be dismissive of the boy toy), Bachardy was, from the beginning, an obsessive worker—he did thousands of portraits just of Isherwood, his first and most devoted subject. (“Don says he is miserable unless he can draw for three hours at the very least, every day,” Isherwood complained in his diary in 1961.) Bachardy admits he’s slowed with age. But most afternoons he can still be found in the studio he and Isherwood had built over their garage in 1976. That’s where he painted his W-commissioned portraits of Marion Cotillard and Tilda Swinton, who gave two of the past year’s standout performances in Two Days, One Night and Snowpiercer, respectively.

Bachardy works very close to his subjects, sometimes only inches away. His explanation for this proximity—like many successful artists, he has perfected his own mythology—is that as a child he always sat very close to the screen at the movies, so that the close-ups loomed even larger. The precise pencil and ink drawings of Bachardy’s early career have since given way to a brushier, more expressive style, but his portraits are still anchored by the eyes and mouth (unless he happens to be painting one of the male nudes for which hehas become increasingly known), and they are always done from life.

When Swinton sat for him, Bachardy was astonished by her coloring. “That paleness was so exciting,” he says. He did four portraits of her over two sessions (she volunteered to return the next day), and he feels that they both were pleased with the results. With Cotillard, of whom he did three paintings in one afternoon and whose features he declares to be near-perfect, he isn’t quite so sure. “A perfect face is the hardest for me to record,” he says. “No matter if someone praises the picture, I usually have a sense of whether the sitter is being entirely frank. That’s the awful situation of the way I work. But still, I’ve never gotten over the excitement of meeting a star in the flesh. That tingle! If I can get something genuine about what it was like to be in the same room, then, uh-huh, I feel it was worth it.”

I notice we’ve been talking for close to an hour, although it feels like much less. It occurs to me that enjoying Bachardy’s articulate, entertaining conversation—he supposes that Isherwood must have also rubbed off on him in this respect—might be the exact opposite experience of sitting for him. As one of his sitters wrote in an essay in the Hollywood book, “If I only had three weeks to live, I’d spend them sitting for Don Bachardy. Because every minute seems like a year.”

Almost simultaneously, Bachardy seems to realize that it is probably time to hang up. Anyway, he has to go. There is a sitter waiting.

The Stars in His Eyes

Tilda Swinton in Snowpiercer “It was very difficult to make the movie Orlando. We went on a fundraising trip to the States, and I read the book aloud between the canapés. It’s called ‘earning your luck.’ You have to humiliate yourself to get the luck—and money—to do what you want to do.”

Portrait by Don Bachardy.

Marion Cotillard in Two Days, One Night “Having a child has not changed the way I act, but it does stop me from bringing drama home in the evening. Most of the time, my characters are not superhappy, full of joy, singing and dancing. You have to protect a kid from a dark mood, and yet I don’t want to protect myself from my characters. It’s a struggle.”

[

Watch a video interview with Marion Cotillard here.](http://video.wmagazine.com/screen-tests/marion-cotillard-cinematic-crush) Portrait by Don Bachardy.

Mark Ruffalo in Foxcatcher

Watch a video interview with Mark Ruffalo here. Portrait by Don Bachardy.

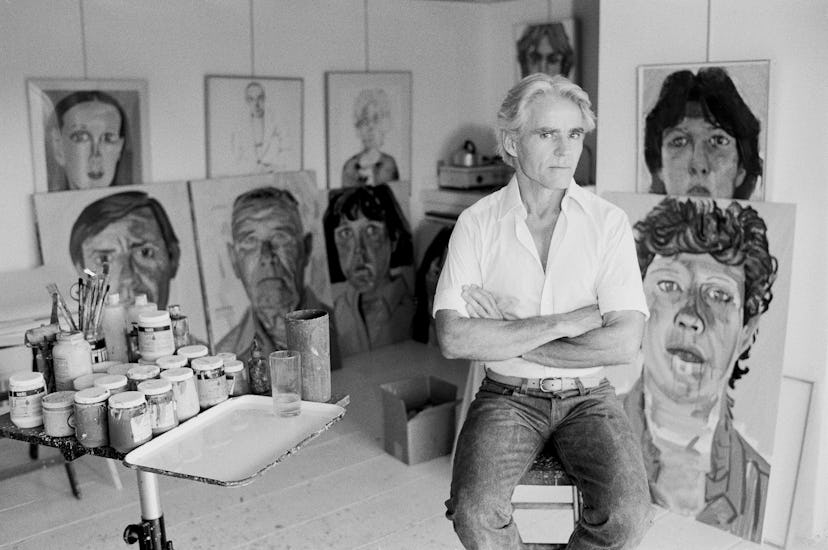

Don Bachardy, in Santa Monica Canyon, Los Angeles, 1970s. Photograph by Michael Childers/Corbis.

Bachardy’s portrait of Natalie Wood, 1963. Courtesy of artist.

Bachardy and the novelist Christopher Isherwood in the early 1950s. Photograph by Zeitgeist Films/Courtesy of Everett Collection.

A 1968 portrait of Bachardy and Isherwood by their friend David Hockney. Courtesy of the artist.

Bachardy’s portrait of Marlene Dietrich, 1963. Courtesy of artist.

Bachardy and Isherwood in the ’70s, in front of the Hockney portrait. Photograph by Zeitgeist Films/Courtesy of Everett Collection.

Bachardy with Marilyn Monroe, early ’50s. Photograph by Zeitgeist Films/Courtesy of Everett Collection.