Butt Out

After five autobiographical essay collections that have sold more than four million copies in 25 languages, a lot of people must think they know David Sedaris pretty well. Certainly his fans are fully versed in the eccentricities of the writer’s sizable Greek-American family and his down-and-out young adulthood. After stints in multiple colleges, he scraped by picking apples, painting houses and playing an elf at Macy’s Santaland, all the while consuming drugs, alcohol and cigarettes in bulk. Happily, things turned around in the early Nineties, when he met his perfect boyfriend, Hugh Hamrick, and, shortly thereafter, was asked to read his essay about the aforementioned elf gig on NPR, which led to overnight fame and a book deal. Sedaris and Hamrick, a decorative painter, soon traded their rat-friendly tenement in New York’s SoHo for a lovely Paris flat. Today the couple divide their time between a Left Bank apartment, a house in a rustic part of Normandy and a town house in London’s Kensington.

Listen to a clip from the Audiobook

David Sedaris’s new novel.

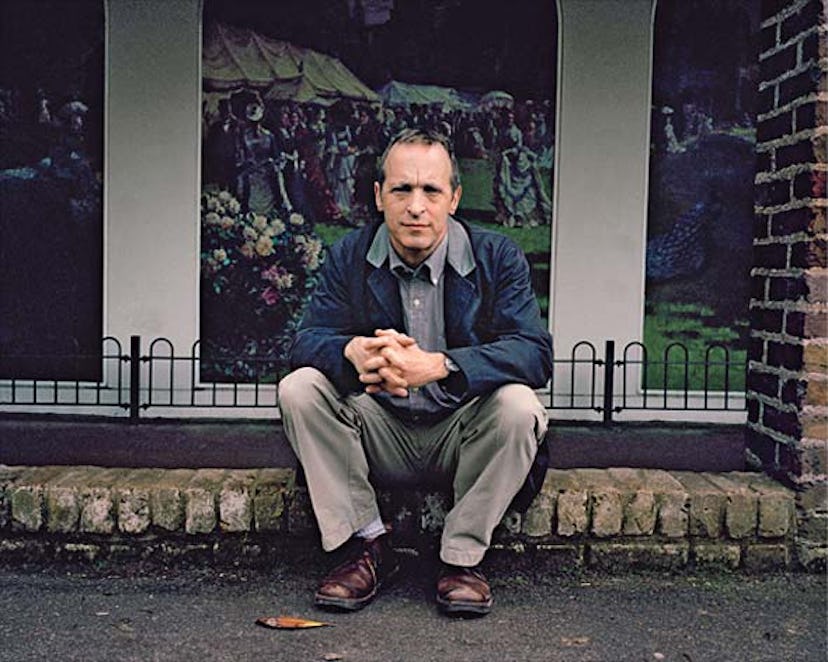

On a chilly March afternoon, Sedaris welcomes me to the Paris place, which is spacious and filled with comfortably worn antique furniture, quirky portraits and numerous taxidermic birds. Wearing khakis and a blue checked short-sleeve shirt, he is as self-deprecatingly funny as you might expect. “I’m No. 1 in Austria!” he faux brags. “Whenever a book of mine does well in another country, I always think, Really? Because people have their own stuff to read. But I’m flattered.”

With the publication in June of a new collection, When You Are Engulfed in Flames (Little, Brown and Company), Sedaris, 51, is about to launch a six-week publicity tour in the States. And since his last U.S. book tour, in 2005, a new challenge has emerged: the legacy of James Frey. These days, in the wake of Frey’s infamous fabrications, it seems every memoirist has to watch his back. Last March The New Republic published a 4,000-word piece by writer Alex Heard, who spent weeks fact-checking the Sedaris oeuvre, talking to his childhood friends and even confronting his then 83-year-old father in person to try to prove Sedaris a liar. In the end, the attempted takedown, a humorless and rather tiresome account of Heard’s gumshoeing, came up with very few smoking guns. Although Heard did confirm that Mr. Mancini, Sedaris’s junior-high guitar teacher, was not quite the “perfectly formed midget” he had depicted, most of his findings were anticlimactic. (A mental hospital at which Sedaris volunteered when he was 15, for example, was not architecturally Gothic, as he’d described, but Tuscan Revival.) Still, the article generated attention.

Sedaris says that his sister Lisa read him a few lines from the piece over the phone but that he hasn’t bothered to read the whole thing. (Predicting that he’ll be grilled about it on his upcoming tour, however, he plans to get a copy.) The irony that The New Republic has itself published some serious falsehoods is not lost on Sedaris. In 1998 staffer Stephen Glass was dismissed for fabricating a series of articles, and just last year the publication’s “Baghdad Diarist,” a columnist who was an army private, was also discredited. “So it’s okay to [make things up] when you are reporting from a war zone, but not if you’re writing about a class you took in fifth grade?” Sedaris asks.

For Sedaris, the most trying result of the brouhaha has been that the notoriously strict fact-checking department at The New Yorker, which publishes many of his stories, has, he says, “gone into overtime” verifying his work. His friends, relatives and even the residents of his Normandy village are frequently called to corroborate minute details. The trouble is, they sometimes have their own versions of events. After, for example, Sedaris referred to a walnut grandfather clock in his family home, his father told the fact-checker he thought it was cherry wood. The younger Sedaris quickly gave in: “I said, ‘Fine, make it cherry!’” But he was in no mood to settle after the checker contacted his sister Amy to ask whether it was true that David paid her a dime for a chicken leg at childhood dinners. She claimed it was 20 cents. Amy, a comedian who cocreated and starred in the television series Strangers With Candy, was “just f—ing with them,” he maintains.

Most recently, Sedaris sent his editor a story about animals. “I thought, I’ll be safe here, shouldn’t be any problems,” he says. But after he mentioned a nature TV program that featured two camels—Josh and his “girlfriend” Josie—the fact-checker obtained a tape of the show and found no mention of the word “girlfriend.” Sedaris almost lost it. “Let me tell you something,” he retorted. “Camels don’t date. Let’s just say she’s a female and they get along.”

“I feel I have always been up-front about how I exaggerate,” Sedaris insists. “But I think a memoir is pretty much the last place an intelligent person would look for the truth. It’s my version of an event, just as my sister Lisa has her version, and my brother, Paul, has his.” Whenever he writes about family or friends, he says, he sends them the piece before publication, giving them the chance to weigh in.

Being something of a Luddite, Sedaris—who does not drive, own a cell phone or have an e-mail account—relies on the postal service for most communication. E-mails, he says, are “always somebody wanting something, and that’s a pain in the ass.” It was only last November that he learned how to access the Internet, and until about 2000, he wrote on a typewriter.

Since going online, Sedaris has surfed the Web a bit (“I turned on that YouTube”) and discovered blogs, the uncensored, sometimes soul-baring nature of which he finds a bit “shameless.” It’s a surprising reaction from a man who has recounted tales of his grandmother’s flatulence and his brother’s success teaching his dog to eat poop, but Sedaris insists he’s quite selective about what he shares with the world. “I’ve been keeping a journal for 30 years, but I’ve never given it to anybody. I read aloud from it sometimes but not higgledy-piggledy. I choose sections I think might be entertaining and I rewrite them, again and again. But I cannot imagine putting my diary on the computer for everyone to read. I would die if anyone got their hands on it.”

One subject Sedaris hasn’t yet written much about is his success overcoming addiction. He gave up drugs and alcohol more than nine years ago. Prior to that, on a typical night he would down five beers and two scotches, then light a joint. “I can whine about it in my diary, but there’s only so much that people can listen to,” he says. “There are some really good alcoholic stories out there—people who set their children on fire. That’s what people want to hear.”

According to Sedaris, his own experience getting sober was far less dramatic. He never hit rock bottom, he insists, but just made up his mind one day to quit drinking. He claims it was the need “to pee every five minutes” from all the liquids that made him want to stop. “So I drank on a Tuesday night, and on Wednesday, I didn’t,” he says. “Today I don’t even think about alcohol, but I still love buying booze and pouring for other people.”

A year ago, Sedaris conquered another addiction: cigarettes. This he has chosen to write about at length in “The Smoking Section,” the longest story in the new book. Because he always smoked when he wrote, he feared that quitting would result in writer’s block. His solution was to go somewhere where all ingrained habits and routines would be shaken. “I had my last cigarette, and then Hugh and I flew to Tokyo,” he says. “The world was turned upside down, so it made perfect sense that I couldn’t smoke. I mean, I’m in my own home and I am not allowed to wear shoes?”

It was in Japan, where the couple remained for three months, that Sedaris stumbled upon the title for his book. In a hotel room in Hiroshima, he found a safety booklet titled “Best Knowledge of Disaster Damage Prevention and Favors to Ask of You,” in which one subheading read when you are engulfed in flames.

Like all great Sedaris stories, “The Smoking Section” ricochets between present and past, with flashbacks to Sedaris’s childhood in North Carolina. Growing up in tobacco country, his fourth-grade class toured a cigarette factory and were given packs to take home to their parents. When, at age 20, he took up the habit, smoking served as a sort of bonding agent with his acerbic, chain-smoking mother, Sharon, who often put cartons in his Christmas stockings and Easter baskets. She died of lung cancer in 1991.

Though Sedaris has always written matter-of-factly about being gay, he never wrote a big coming-out story (“Everyone’s got their coming-out story,” he says. “That doesn’t mean it’s any good”), perhaps because he never had a “TV-movie-of-the-week moment” of telling his family. Instead, he simply referred casually to a “guy I’m seeing,” at which his parents did a double take and then dropped it. “We’re not very direct people,” he explains. “My dad, he’s a product of his generation. For him to have become as accepting as he has is really something. For me to expect more would be greedy.”

Shortly after this discussion, the door opens and in comes Hamrick. Born in Kentucky, he has boyish all-American looks, though he grew up in Congo, Somalia and other countries where his father worked for the State Department. A frequent theme in Sedaris’s writing is Hamrick’s handiness: He’s up chopping wood at dawn, for example, while Sedaris slumbers till noon. And true to form, Hamrick proceeds to whip up a delicious dinner of roast chicken and vegetables while Sedaris uncorks a Bordeaux—from which he, of course, abstains.

Amazingly, living with a memoirist has not made Hamrick self-conscious. “David cuts me out sometimes. He’ll say I am not ‘intrinsic’ to the story,” says the painter with a grin. “And he rarely writes about the stuff I think he’s going to. He writes about things I didn’t give a second thought to.” To which Sedaris says he always has the same reply: “Why would I not write about that? That’s gold.”

Sedaris: Karen Robinson/Retna Ltd.; book cover: courtesy of Little, Brown and Company.