The Photographer Who Was There When Punk Was Born, and When It Died

A profile of the photographer David Godlis, whose new book, History Is Made at Night: Photographs 1976 – 1979, is the defining document of CBGB’s and the Bowery.

Last summer, John Varvatos threw a party at his Bowery store in New York, on the occasion of Men’s Fashion Week. The list was overbooked, and by 9 p.m., as rock music bled onto the sidewalk, harried publicists had mostly given up trying to corral a swelling crowd. Inside, Varvatos hopped onto the stage at the back of the store to introduce the night’s entertainment, a quartet of young men with guitars and long hair whom he called, with more than a little dissension in his voice, “the future of rock and roll.”

If you squinted, you may have thought this is what things must have looked like 40 years ago, when this was CBGB, the grody petri dish of punk rock and the seat of a downtown demimonde that has by now died away.

Of course, it’s been modish to declare punk dead since sometime around two weeks after it started. Forty years on, it’s getting harder to ignore the funeral march. St. Mark’s Place is a plein air playpen, Patti Smith is writing about watching Law & Order marathons, and a mural of Joey Ramone adorns a wall outside a restaurant where $58 buys you a 28-day dry aged bone-in NY strip. Unless you need another high-minded taco dissertation, the boatman came for the East Village years ago.

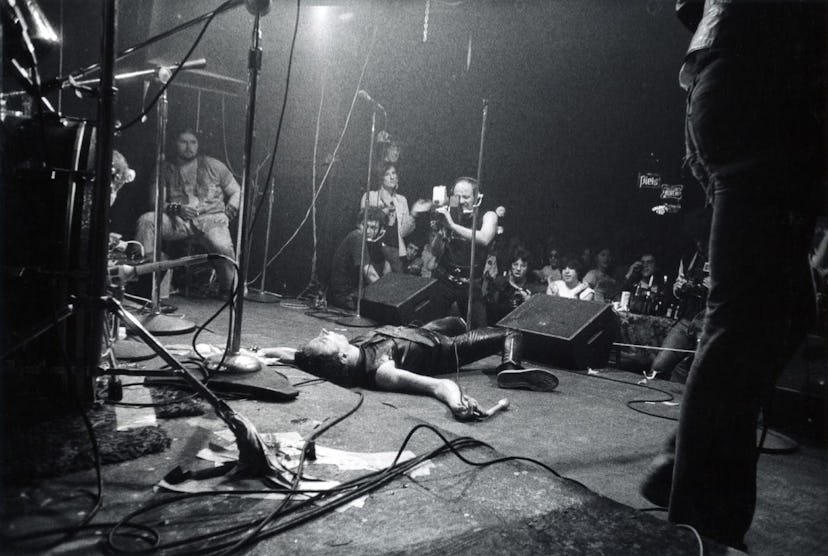

Dictators, 1976.

Today, 315 Bowery is more like a well-merchandised trophy room for Varvatos, a rock and roll game hunter whose shop wears CBGB’s walls like a Cape buffalo pelt. If the designer considers the address hallowed ground, he telegraphs as much up front, displaying a rack of votives for supplicants to partake in the sacrament, a partial absolution, perhaps, for the sin of selling $3,000 leather cutaway coats in the spot where Stiv Bators auto-asphyxiated himself with a mic cord and dragged a broken bottle across his chest.

In the mid- and late 1970s, the narrow spit of a club on the Bowery might as well have existed at the end of the world, a flophouse-forward section of Manhattan that even “Ford-to-City: Drop-Dead”-era New York preferred to ignore. And it was, if you ask the photographer David Godlis, perfect.

Godlis’s images of the CBGB scene have been circulating for years as part of other projects. When the Met’s Costume Institute reanimated CBGB’s dripping, graffiti-caked bathroom for its 2013 punk exhibition, it worked off of Godlis’s archives. More recently, they figured into the Queens Museum’s 2016 show, “Ramones and the Birth of Punk.” But for the first time, over a hundred images Godlis made between 1976 and 1979 are collected in what he considers to be their intended form: a photo book called History is Made at Night.

Patti Smith on the Bowery, 1976.

The raucous shows are remembered—Richard Hell and Patti Smith, Blondie and Talking Heads, sweaty youths and haircuts to regret—but the images show a humanistic interest beyond the gut-punch reverb. Here are surprisingly tender moments in the club and around the East Village: Dee Dee and Johnny Ramone cooling out on the Bowery; Bob Gruen in a fur parka on Bleecker Street; Andy Warhol taking in a Mumps show.

Godlis approached the Bowery like Brassaï did Paris, eschewing flash and siphoning natural light into gauzy images, as though taken in the part of New York that was barely lit to begin with. The pictures seem to hum, their subjects seeping in and out of their own shadows. Patti Smith’s hand, disjointed from her person, comes to rest on her face like Dorothea Lange’s “migrant mother” transported to the corner of Bleecker Street. Richard Hell clatters through a Bowery rainstorm, phantom limbs vibrating between drops. Debbie Harry on stage is all slink, a penumbral spectre. That quality lends the book a film noir affect, more Billy Wilder than Charles Boyer, a romantic nocturne in long exposures.

History is Made at Night takes a gestalt approach, presenting the rarely-seen faces of a place that would lurch to life at night and cease to exist by morning: Roberta Bayley—who shot the portrait of the Ramones used for their debut album cover, and who would later become Blondie’s longtime photographer—at the door and manning the phone, her finger plugging one ear; Sylvia Reed and Anya Phillips in matching proto-versions of the all-black downtown uniform; a kid getting a punk haircut, which is someone lighting your hair on fire. Godlis shot all night, from the shoal of people waiting to get inside CBGB to the club emptying out at 4 a.m., chairs upturned and a garbage truck backed up to the door.

Klaus Nomi, Christopher Parker, Jim Jarmusch, 1978.

“What a garden of amazing shit!” writes Jim Jarmusch in an introduction to the book, recalling his younger self, still in film school at nearby NYU. “And none of it mainstream, none of it forced down your throat. There it was, almost a secret, growing and thriving in a dark, dirty bar down on the Bowery … artifacts of a little scene that eventually changed lives and perceptions and possibilities.”

Godlis was born in uptown Manhattan in 1951 and studied English literature at Boston University. By his sophomore year, he got a camera and started taking pictures of friends. He went to New York in 1972, the year after Diane Arbus’s suicide, to see her MoMA retrospective. “That pretty much clinched it,” he told me. “That completely opened me up to what I could do with photography.”

He enrolled in the Imageworks School of Photography in Cambridge, Massachusetts, taking classes alongside Nan Goldin and burying himself in the recent history of street photography. He returned in 1976 intent, he said, ”to walk up and down the streets of New York and take pictures,” a dream easier imagined in an era when the $205 rent for a Soho apartment could be reasonably described as “too expensive.” Godlis took a cheaper walk-up on St. Mark’s Place recently vacated by the late 60’s radical Abbie Hoffman, where he still resides.

Lydia Lunch, 1977.

Godlis arrived at CBGB, like most everyone who found their way there, as someone simply looking for a place to go. An ad in the back of the Village Voice for a club featuring bands with outré names (”Who called themselves ‘Television’”?) lured him down to the Bowery.

There’s a scene in Spike Lee’s Summer of Sam, where Mira Sorvino and John Leguizamo, playing a couple from the Bronx, drive down to CBGB to see their friend Adrien Brody play a gig there. They roll up to a popular image of the club as carnival nightmare: a bombed-out Bowery, rabid punks pierced in untoward places hissing at them from the sidewalk. They decide to go to Studio 54 instead.

“You know, people ask me, ‘What did it look like?’” Godlis said. “It was wide-open boulevards, devoid of anything at night. There were no businesses running except, like, a gas station, and bums—you know, Bowery Bums—and just big empty space. It’s hard to imagine New York with big, empty spaces, but this was one of the biggest empty spaces. The bums moved slow. They weren’t coming after you.”

No wave punks, 1978.

If the place was accreting its famed patina then, Godlis hadn’t noticed. “You walk in and what I remember is, Okay, this looks like a bar. I mean, it didn’t look scary or anything. It was just like, It’s got a pinball machine, it’s got a jukebox. And then Television played. I walked into the room where it was, like, The future was here.”

He took a few pictures that night, but back then “music photographer” was not considered an artful calling. “This place happened to have good music, but it wasn’t spurring me on to be a rock photographer,” Godlis recalled. “I loved photography. I got so knee-deep in how cool it was that, to me, being a guy walking around with a 35-mm. Leica shooting on the streets of New York was as cool as being a rock star walking around with a guitar. You know, in my mind.”

The revelation, as it were, came to him on a well-lubricated night at CBGB’s bar. The Secret Paris of the 30s, Brassaï’s photo memoir, had just been released, and Godlis had been studying it like a Sumerian rune in the mornings over coffee at the Times Square Burger King before he had to show up to his job as a studio assistant. Brassaï’s atmospheric evocation of an afterhours bohemia had colonized his mind. He thought: “Maybe I don’t have to be a street photographer who shoots during the day. Maybe I could be a street photographer at night, and do what Brassaï did in the 30’s, here, in the 70’s.”

The Ramones, 1977.

Not everyone was as possessed by this idea. “I went back to Boston to show people I went to art school with this thing I was working on, and they were like, ‘This is your new work?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, this is this club, down in New York.’ None of them had heard of it,” Godlis recalled.

“I said, ‘Look, I’m showing you the news.’ And I’d play a 45 of the Ramones, and they’d go, ‘Oh, you’re photographing bad musicians.’ So I went from photographing musicians, which was down here”—he dropped his palm toward the floor—”to photographing bad musicians,” dropping his palm further. “It just took another year or two for the same people to tell me they always thought I was doing the right thing,” he went on. “I realized there’s just a shift in time that hasn’t happened yet. And this was the one place where it was happening.”

“There are all these hierarchies in photography,” explained Gail Buckland, a professor of photography history at Cooper Union and the curator of “Who Shot Rock & Roll,” a 2009 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum which featured some of Godlis’s work. Buckland agreed that for a long while, rock photography was something of an unloved foster child of fine art image-making. “It was like this black hole, which is very curious, because Lee Friedlander loved jazz and photographed jazz musicians. The Museum of Modern Art exhibited Roy DeCarava’s jazz musicians, but they never touched rock and roll. It was bizarre, because a good photograph is a good photograph. But street photography is different. It’s a response to a feeling of what’s going on, a rhythm, so it’s more appropriate to the scene that was happening.”

Blondie, 1977.

“I think David is the voyeur, in the best sense of the word, a voyeur the way Brassaï was,” she went on. “I don’t get the impression he was getting high and going crazy, I get the impression he was there, he was a creative eye watching the scene, and he never lost sight that he was a photographer.”

Still, did anyone register the historical import of what they were doing?

“If there’s a punk way of thinking there’s a historic moment, definitely people thought that the Ramones were the Beatles at the Cavern Club, that they were going to be really big,” Godlis said. “You felt that this was the most amazing thing that was happening in New York City. And, yeah, you did feel that there was some history involved, but how much history do people in rock and roll really feel?”

Godlis’s photographs are a defining document of a loud, evolutionary movement that burned hot and fast. Looked at now, this period of rock’s primacy feels distant. And when you consider the state of rock’s relationship to fashion, which is mostly non-existent, it can feel embalmed. The culture-fashion industrial complex has centered itself fully around hip-hop and Hollywood, which makes Varvatos seem like one of the last archivists of a once-dominant aesthetic, and Godlis’s images function as an act of cultural preservation. History is Made at Night is currently stocked at Varvatos Bowery, which, depending on your tolerance for irony, is a fitting coda, or it’s too much to bear.

Godlis gets to talking about the Queens Museum show: Four friends from Forest Hills who sang about sniffing glue, holding court in a major art institution? Surely now, punk was finally, thoroughly dead.

“You know, you sit in that room and listen to The Ramones—and they’re dead—but the music has a remarkably potent effect on people. On me, still. I sat there and I looked at a Ramones show from 1977 and I’m listening. There’s still layers of the onion people don’t know about, you know, because everyday there’s something new that seems to come.”

After Hours Pictures of Patti Smith, Blondie, and the Ramones Like You’ve Never Seen Them Before

The scene outside CBGB.

Chris Stein, 1977.

Patti Smith, 1976.

Chris Parker, 1977.

Dictator, 1976.

Ramones, 1977.

Sylvia Reed and Anya Philips, 1976.

Klaus Nomi, Christopher Parker, Jim Jarmusch, 1978.

No wave punks, 1978.

Richard Hell, 1977.

Joey Ramone, 1977.

Blondie, 1977.

Talking Heads, 1977.

Roberta Bayley, 1977.

Alex Chilton, 1977.

The Ramones, 1977.

The Bowery, 1977.

Dead Boys, 1977.

Nico, 1979.

Suicide, 1977.

Fran Pelzman & Mary Harron, 1977.

Lydia Lunch, 1977.

Hilly Cristal, 1977.

Closing time, 4 a.m., 1977.

Bowery garbage truck, 4 a.m., 1977.