Cy Gavin, a Young Artist With an Eye For History

In his upcoming solo exhibition, the painter revisits a scarred time in the colonial era of his ancestral Bermuda.

The artist Cy Gavin thinks of paintings as “time capsules,” repositories for the experiences they contain. Last summer, in his debut New York solo show at Sargent’s Daughters, Gavin included his father’s cremated remains in his portrait of him. For his latest show, opening Friday at the Chinatown gallery, Gavin, 30, incorporated his own blood and pink sand from Bermuda, the setting for the paintings on view.

For much of the past year, Gavin has been in Bermuda, his father’s birthplace, where the artist has relatives he’s never met. He preferred to keep it that way while he built his own relationship with the island before transmitting his journey to canvas and video.

To that end, he slept on the beach and stored his cameras and food in a limestone cave. He drew, painted, and photographed the island’s geology and native plants, and read up on its central role in the history of slavery, as a way station for ships bearing enslaved Africans en route to the West Indies, Mexico, and the American colonies. “It was very lonely,” said Gavin, who is completing his MFA at Columbia this May. “I was thinking of how my ancestors may have beheld this land, with all its exquisite beauty marred by the atrocities perpetrated by the British. It is not hard to imagine all of the dead who would have likely been cast cavalierly into the crystal clear waters.”

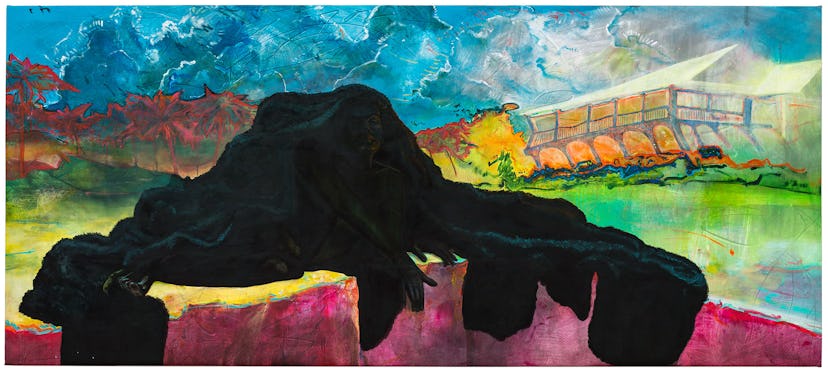

The artist stood on the site where an elderly female slave named Sally Bassett was burned at the stake (for allegedly poisoning slaveholders), and slept in a cave once inhabited by a runaway slave named Jeffrey. At the Historical Society Museum, he pored over documents, “amazed to find not one word of slavery in the entire place.”

The title of his show, At Heaven’s Command, corrects that omission: It’s a phrase lifted from the British anthem “Rule, Britannia,” which was penned during Bermuda’s slave period. Gavin’s portrait of Bassett includes seeds of the Bermudian iris because, according to local folklore, they were said to have sprouted from the accused slave’s ashes as a sign of her innocence.

Gavin refuses such labels as figurative painter, and it’s easy to see why: his paintings give equal weight to the ghostly figures in the foreground and the landscapes that give rise to them. Many call to mind works by Peter Doig, Kerry James Marshall, and even Gaugin. Having once worked as an opera producer, Gavin supposed his use of color is informed by the “hyperbolic theatrical gel lighting” used onstage.

However, though he once headed post-production for Falcon Studios, a producer of gay porn, he rarely thinks of bodies, per se, or about one particular kind of body, as he paints. “At some point, I made the decision to paint figures using a variety of materials and colors to approximate black,” he said. “I was trying to visualize an idea of a conflated black identity, not just the experiences of African Americans. I think of the self as a living expression of the sum total of ancestral genetic material, of eons of traditions and wisdom.”

Photos: Cy Gavin, a Young Artist With an Eye For History

Rosewood Tucker’s Point Golf Club and Cemetery, 2015.

Courtesy the artist and Sargent’s Daughters.

Aubade II (Spittal Pond), 2016.

Courtesy the artist and Sargent’s Daughters.

Sally Bassett, Laughing (at Crow Lane), 2016.

Courtesy the artist and Sargent’s Daughters.

Jeffrey’s Cave, 2016.

Courtesy the artist and Sargent’s Daughters.

The Future of Tucker’s Point, 2015.

Courtesy the artist and Sargent’s Daughters.