When Noah Lemaich took his post behind the concierge desk at 60 Thompson hotel in New York’s SoHo one morning, he anticipated just another average day fulfilling guests’ pleas for theater tickets or dinner reservations at the Waverly Inn. But then he received a phone call from a female guest with a particularly pressing problem. She wanted breast milk delivered to her room within the next two hours. She didn’t say why, she didn’t say how much, and she didn’t say from whom it should be procured.

“I’m assuming maybe there was a child involved somewhere,” says Lemaich, who has been the hotel’s concierge for five years. “It’s like, is there some kind of questionnaire I should be asking this person, or is just anybody’s breast milk fine?”

Through his connections at various baby-equipment rental agencies, Lemaich located a breast-milk supplier (he won’t divulge specifics) and within a few hours had several cooler bags of the milk delivered to the hotel. Lemaich was thanked for his services, he says, but in a way that was “like this is a normal, everyday type of thing, just like opening the door for them.”

Not too long ago, the most extravagant thing a guest would ask of a concierge was to sprinkle the bed with rose petals. Twenty years ago, “people didn’t even know what we did,” says Abigail Hart, who worked as a hotel concierge for more than two decades, most recently at the Four Seasons Hotel Chicago. “They were too embarrassed to use our services. They thought it was reserved for VIPs.” But these days, it’s not unheard of for a guest to call the concierge—sometimes multiple times a day—with requests to, say, locate a masseuse for a dog or to replace all of a room’s standard lightbulbs with pink ones.

“Ten years ago, people relied on the concierges for pretty basic information—nice places to go for dinner, good neighborhoods to shop in,” says Diane Clarkson, a travel analyst with Jupiter Research. But now that a quick Google search can often summon the information guests need, she says, “concierges are having to reinvent themselves.”

To some degree, it’s luxury hotels that have encouraged this new level of dependence. With average room rates so high, “it’s very competitive,” says Clarkson. “If loyalty is something that you’re really needing to drive with your guests, the concierge is in a pivotal position to do that.” For hotels charging upwards of $500 a night, promising—and actively promoting—a nearly absurd level of service has become almost mandatory. The One & Only Palmilla in Los Cabos, Mexico, for example, brags that its butlers will custom-program iPods for guests to enjoy while lounging poolside. The Sandy Lane in Barbados crows that its staff will even clean your sunglasses for you.

“Nothing is unusual anymore,” says Amy Bowman, chief concierge at the Peninsula New York, who once was asked at 6 p.m. on a Friday to locate a female bichon frise puppy—under six months old and housebroken—that could be delivered to a guest by Saturday afternoon. (She ended up finding one through a local pet shop.) Mariajosé Rodríguez, concierge manager at Las Ventanas al Paraíso in Los Cabos, once received a request for a $1,500 bottle of Cristal Rosé Champagne, which was not available in Mexico. She had to send a staffer across the border to buy it. Even the W hotel chain, where the clients are more often young professionals than Hermès-carrying heiresses, aggressively advertises its “whatever/whenever” capabilities. (Guests can use a text message program to convey their ever important needs directly to the concierge’s cell phone.) Marcelo Surerus, the area concierge director for the W Hotels of New York, says one of his colleagues loaned a guest the very shoes off his feet so the businessman could run to an important meeting.

Melissa Biggs Bradley, founder of indagare.com, a members-only luxury travel Web site, agrees that hotels have “trained the consumer to understand the idea of really customized service.” But she believes the rise in guest demands might also be a direct response to the soaring rates. “When people are traveling, particularly in grand hotels, they often get a sort of princess complex, and all of a sudden they’re doing things they wouldn’t pull at home,” she says. “If they’re paying X number of dollars a night, they think everybody around them should literally be serving them.”

Former Four Seasons concierge Hart, who has chronicled her 20-plus years behind the desk in a forthcoming book, Great Reservations (Three Rivers Press), felt such was the case when one of the hotel’s regulars booked a room for his ailing mother. Instead of hiring a professional nurse to attend to her, he asked Hart to look after her. “He was quite a tightwad,” recalls Hart. “I think he thought, Heck, I’m paying for this expensive room, I’ll have Abby do it.” Hart bathed the elderly woman and says she ended up bonding with her.

For some guests, Hart says, challenging the concierge to fulfill odd requests becomes almost a game. “They keep on adding a few things just to see if we can do it,” she says. “And, you know, we will.”

Then again, there are demands even the most dedicated concierges won’t satisfy for even their most VIP clients. In the business the basic tenet is “nothing illegal or immoral,” says James Little, a concierge at the Peninsula Beverly Hills. “I assure you I have been asked to do both.” Outside of those parameters, the other most frequent request that concierges refuse: double- or triple-booking restaurant reservations. “It would ruin our good rapport with restaurant owners, and in turn they wouldn’t work with us,” Hart explains.

Indeed, if the first credo of a good concierge is to say yes to almost everything, the second is to maintain a poker face and keep the prying to a minimum. Lemaich, the breast-milk hunter at 60 Thompson, says that one day he found himself shipping a pink gorilla suit back to a guest’s office in Italy. “I’m not going to have a reaction to that if that’s not what they’re looking for. I had to treat it like a normal, everyday task. Hey, great, no problem, I am shipping this gorilla suit to your office in Italy,” he deadpans.

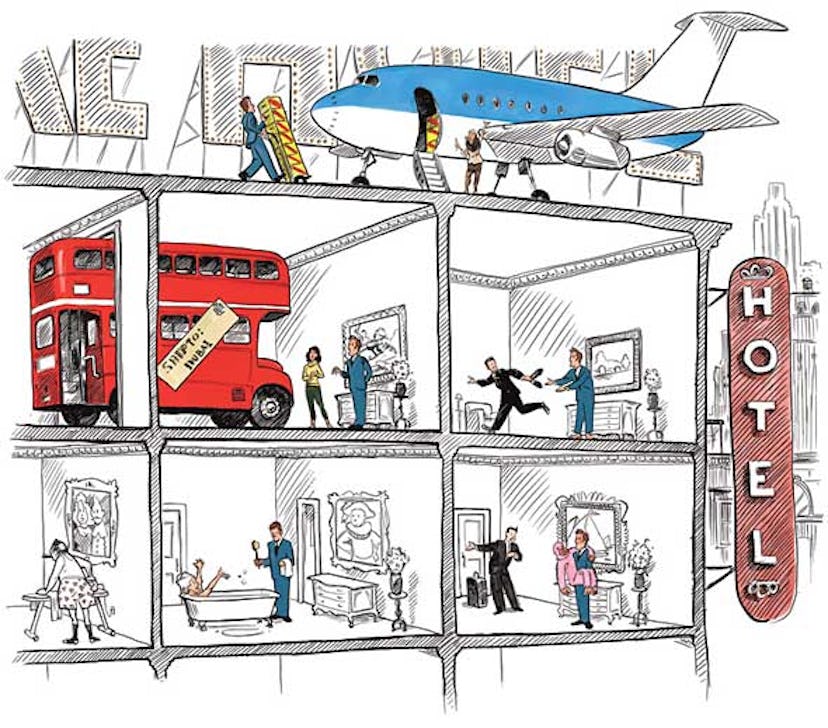

When one guest asked the staff at the Times Square W to help purchase a double-decker bus and have it shipped back to her home in Dubai, Surerus says, “the only question that we had to ask was what color.” (Through the bus-tour company Gray Line, he found a dealer in England who let the guest order a bus by phone.)

For the most part, concierges claim that the challenge of fulfilling their customers’ wacky or over-the-top needs is part of the job’s appeal—though everyone, of course, has his limits.

Says Lemaich, “There are definitely days when I want to hide behind the desk.”