Meet the Parents

Christopher Buckley pens a bittersweet memoir of his celebrated but formidable mom and dad.

When Mom is social queen of New York and Dad is the Right’s leading intellectual, your childhood—and adulthood—are bound to be perfect memoir fodder. Christopher Buckley, though, long ago resolved not to write a book about his famous parents, Patricia and William F. Buckley Jr. But after his father died of a heart attack in February 2008, just 10 months after his mother’s death, Buckley, a novelist and political satirist, changed his mind. Apart from the “amazing material” he knew he had, he found that he also had some issues to work through regarding his conflicted relationship with his parents and theirs with him—and with each other. “It poured out of me,” says Buckley, recalling that when he finished the memoir, he realized he’d been in a virtual writing trance for 40 days. “Nothing biblical is intended by that,” he says with a laugh over a plate of risotto at Cafe Milano, a bistro in Washington, D.C.’s Georgetown neighborhood. Clad in a blue blazer, blue shirt and gray pants, the 56-year-old resembles a well-preserved preppy, with courtly manners and a wry sense of humor.

Christopher Buckley at Cafe Milano in Washington, D.C.

Although rumored to be a hatchet job, his memoir, Losing Mum and Pup (Twelve), he insists, is nothing of the sort. “This is not Daddy Dearest or Mommie Dearest,” Buckley says. “This is a love story. It just happens to be, like many love stories, a complex one.”

Readers can discern as much when, early in the book, Buckley, an only child, describes his 80-year-old mother being unplugged from her respirator at Stamford Hospital, where she had lapsed into a coma in 2007 after septic poisoning following a vascular operation. Buckley had learned that Pat was in her final hours earlier that day, after lecturing in Lexington, Virginia, and he found a livery driver willing to make the eight-hour trip to Connecticut. “It was quiet and peaceful in the room,” he writes of the scene, after he gave the doctor the okay to remove his mother from life support, his father having been too frail and distraught to make the decision. “I stroked her hair and said, the words surprising me…‘I forgive you.’… I didn’t want any anger left between us.”

“That line just happened—there is no planning for those things,” he says, quickly flagging down the waiter to order a “glass of that lovely Sauvignon Blanc,” as if to change the subject.

While Buckley refers repeatedly in the book to periods of strife and estrangement among all parties—his mother wasn’t speaking to his father “about a third of the time,” and he often cut off contact with both parents for months on end—he generally avoids addressing the causes of these rifts. “I left out a lot of stuff—you have no idea,” he says emphatically. “I didn’t want to write that kind of book,” presumably meaning a tell-all. Naturally, these withholdings can tantalize, if not frustrate, the reader. During this interview, he is almost as circumspect. “You’ll have to draw your own conclusions,” he says several times.

Christopher Buckley’s book.

He does, however, elaborate on some aspects of his parents’ relationship: There were, he notes, three people in the marriage. “I was the person in the middle,” says Buckley. “We clashed often. I was sort of tapped as a go-between marriage counselor. [Pup would say,] ‘You won’t believe what your mother’s done now.’ That’s not really fair, but I’m not complaining, exactly,” he adds.

As she emerges in his book, Pat, with her over-the-top wit, could be hilarious as well as exasperating—thanks to her often imperious manner. Her “serial misbehavior,” as Buckley calls it, also included a tenuous relationship with the truth, something he first noticed at about age six, when she announced in front of guests that “the king and queen always stayed with us,” referring to King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. Colorful as these whoppers could be, Buckley is loath to call them lies. “Prevarications,” he says wryly.

But as Pat grew older, a meanness crept into some of her tall tales. In his memoir, Buckley recalls the night a few years ago when his daughter went to visit her grandmother at her Stamford estate, bringing along her best friend, Kate Kennedy. At the dinner table, Pat claimed (untruthfully) to have been an alternate juror at the murder trial of Kate’s father’s first cousin Michael Skakel, and launched into a lecture on his villainy. Buckley wasn’t speaking to his mother at the time, and when told about it, he was too upset even to write her one of his frequent “scolding—occasionally scalding—letters,” as he describes them. “I think it was [her] insecurity factor—a way of overcompensating,” he says of her behavior. Although her father, who had timber and oil interests, was one of the richest men in Canada, “she was a woman with some fundamental insecurities,” Buckley says. Brought up in “the backwoods of British Columbia,” as Pat used to say (though her family’s house occupied a city block in Vancouver), she attended Vassar but dropped out at the end of her sophomore year—for reasons never fully explained, according to Buckley. The following summer, she married Bill, who had just graduated from Yale. Her habitual fibbing, surmises her son, may have come from her feelings of inferiority, which were no doubt exacerbated by living in the shadow of a man of formidable intelligence. Yet Pat possessed “a very fine mind,” states Buckley. “She [could do] the entire Sunday Times crossword puzzle, which I can’t do.”

In later years, Pat’s drinking became increasingly problematic. The subject comes up in his memoir and in our interview, but Buckley stops short of calling her an alcoholic. “I’m not going to use that word into your tape recorder, having carefully avoided it over the course of 250 pages,” he says. When asked for comment, several close friends of Mrs. Buckley were also reluctant to call her an alcoholic. “But when she drank, she did become more aggressive, more belligerent,” says one. Kenneth Jay Lane, a frequent Stamford houseguest, disputes that. “Pat liked her wine, but she could hold her liquor,” he says. Buckley brightens considerably when he brings up Pat’s better qualities. “I don’t think there was a wittier woman on this earth, or wittier person,” he says. “She had a delicious grasp of the ridiculous.”

Though his mother was a veritable pillar of the International Best-Dressed List, Buckley admits he didn’t always appreciate her celebrated style. One of his first inklings that Mum was not like the others came at about age 14, when he was attending a Benedictine monastery boarding school in Rhode Island. News from the outside world seeped in courtesy of the switchboard operator, a fat, gossipy woman whose reading material included the “Suzy Says” society column, as he recalls in his book: “‘Your mutha went to a big party last night for Walter Cronkite!’ she would yell out at me into the crowded room where we checked our mailboxes. ‘She wore an Eves Saint Lawrent dress! Musta cost a fortune!’”

Retelling the story over lunch, a wistful smile comes to Buckley’s face. “I can still hear it—I wanted to die,” he says.

Buckley pens a similarly mixed portrait of his father. WFB, as he was widely referred to, comes through as a great man who didn’t always have time for his son. Ten minutes into Christopher’s Yale graduation ceremony, Buckley Senior grew bored and took the other family members to lunch, leaving Christopher to wander the campus in search of them. As Buckley’s own career and stature as a writer grew, his father was sometimes stinting in his approval. “This one didn’t work for me. Sorry,” he wrote in the postscript of an e-mail to his son, referring to Buckley’s new novel, which was receiving rave reviews. Recently, however, going through the numerous e-mails he’d received from his father, Buckley found compliments on his pieces in The New Yorker and other publications. “I may have been a little hard on [my father]—but not by much,” he says.

Yet Buckley speaks lovingly of many aspects of his relationship with his father. They bonded on long sailing trips, including voyages across two oceans. He cast his first vote at age eight—in 1960, for Richard Nixon—on WFB’s lap.

Since his parents’ deaths, Buckley’s life has hardly been drama-free. After he endorsed Barack Obama last October in a post for the Daily Beast, the right wing launched a veritable fatwa against Buckley, a heretofore loyal Republican who once worked as a speechwriter for then Vice President George Bush, while the National Review, the conservative magazine his father founded in 1955, hastily accepted his gentlemanly resignation—to his surprise. “I am very mindful of the NR being Pup’s proudest creation,” he says. “I feel really bad this happened.”

More-salacious items have appeared in gossip columns, on the matter of a lawsuit brought by a former Random House publicist, Irina Woelfle, with whom he fathered a son, Jonathan, now eight years old. Woelfle is seeking an increase in the $3,000-a-month child support currently being paid by Buckley, who remains married to his wife, Lucy, with whom he has two children, Caitlin, 21, and Conor, 17. After his father died, it was revealed in the Hartford Courant that WFB had left the child out of his will: “I intentionally make no provision herein for said Jonathan, who for all purposes…shall be deemed to have predeceased me.” Buckley declines to discuss the will, stating that “[Jonathan] is provided for,” and says that he is constrained from speaking about Woelfle’s suit. “It’s a legal matter,” he says. “But I am working very hard to resolve it. I look forward to the time when I can talk about it.”

His ambivalent feelings toward his parents seem to be more resolved as a result of writing his book: “I hesitate to use the word ‘cathartic,’ because it is so overworked. But these are times you’re grateful to be a writer, because you can work it out with words.”

He adds, “I suspect it was a way of spending a little more time with them. During those 40 days I was writing, it was a reimmersion, an intense communion, with their ghosts.” Just what his parents might think of such a public tête-à-tête, Buckley isn’t saying, though one assumes they wouldn’t approve. But maybe that’s beside the point. “Even as I was typing the hard parts, somehow the bad stuff got drained out,” Buckley says. “I feel very much at peace with their memories.”

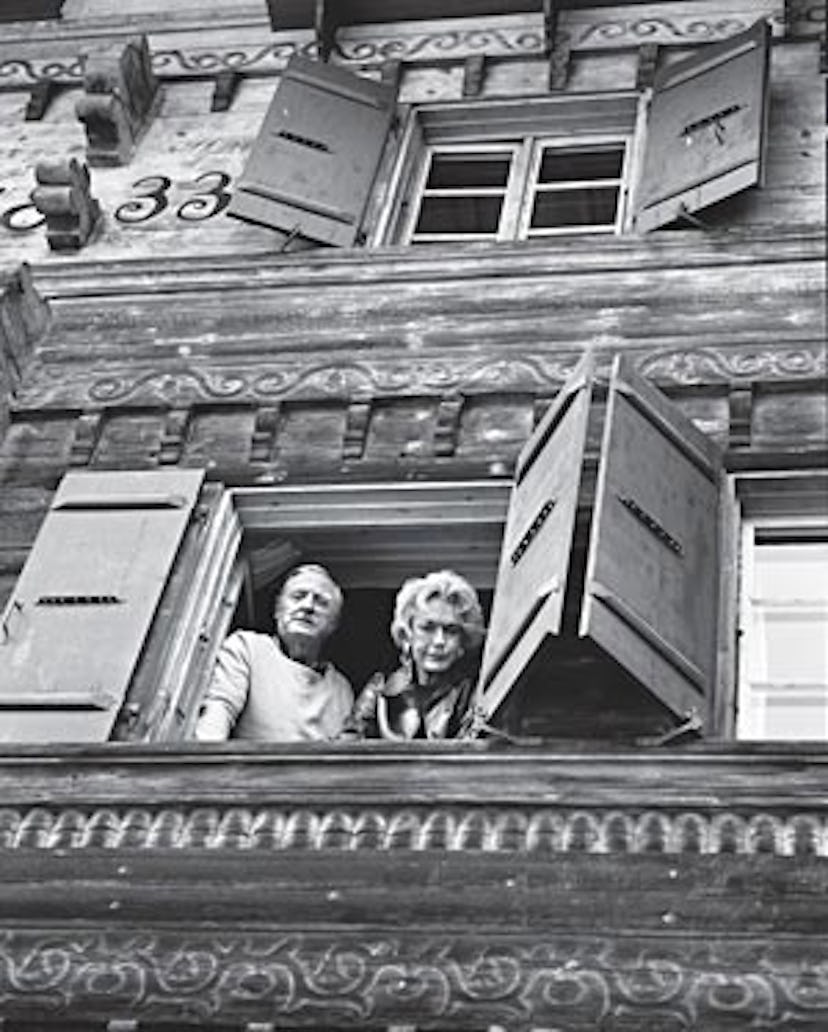

Christopher Buckley: Jesse Burke; William F. and Patricia Buckley: Stewart Ferebee; Book cover: Courtesy of Twelve Publishers