How Chelsea Manning Covertly Made a High-Tech Art Exhibition While In Prison

Her collaboration with the artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg points out that we are all 99 percent Chelsea Manning.

Besides grabbing a slice of hot, greasy pizza and sipping on champagne, one of the first things that Chelsea Manning, famed whistleblower and trans activist, did following her release after seven years of a 35-year prison sentence was go out to brunch for some avocado toast—a normal enough activity for someone getting reacquainted with contemporary American society, but one that held extra significance for Manning. The meal marked her first real-life encounter with Heather Dewey-Hagborg, the artist to whom she’d been sending DNA samples for years.

Before that, the pair’s collaboration, which is now publicly on view at New York’s Fridman Gallery through September, had been largely clandestine. The former U.S. Army intelligence analyst’s spell at five different facilities over the last seven years, which a United Nations expert called “cruel” and “inhumane,” allowed for little outside contact—which is why, in 2015, when Paper wanted to publish a portrait of Manning along with an interview conducted via email and “encrypted web platforms,” the magazine resorted to unusual methods and called on someone who was then arguably one of the industry’s least popular artists.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Radical Love, Chelsea Manning, 2016. Installation at World Economic Forum.

At that point, Dewey-Hagborg’s infamous portraits constructed out of the DNA extracted from found items like cigarette butts and chewing gum had attracted the artist her fair share of flack, but in this case, they provided the perfect phenotypic opportunity: A couple of ear swabs and hair clippings later, she was able to create two 3D-printed portraits of Manning—the first images of her seen since 2010. They were also the first images of Manning, who was known as Bradley Manning at the time she was sentenced, since she announced that she was transitioning. “The only thing, really, was that she was concerned about appearing too male,” Dewey-Hagborg recalled recently of her early interactions with Manning.

Dewey-Hagborg’s infamous, intentionally provocative DNA works were always intended not only as a warning about the risk of surveillance, but of the potential harm of the emerging technology of DNA phenotyping and its reductionism when it comes to identity, particularly stereotypes and biases. Essentially, her interests lined up neatly with those of Manning, a dissident who’s also vigorously campaigned for human—particularly transgender—rights. The pair’s correspondence continued long after the Paper project, even though it had to be mostly via letters, written on actual pen and paper.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg, DNA Extraction Process, Radical Love, Chelsea Manning, 2016.

Together, their previous collaboration grew to 30 more portraits of Manning, which called for much more immediate action—and more swabs and hairs smuggled via Manning’s lawyer. Dewey-Hagborg fed these samples into the software she wrote back in 2012, which analyzes the DNA extractions to create a probable face based on the genetic data. (The possibilities are almost endless: Manning’s DNA alone could result in light skin or dark skin; brown eyes or blue eyes; freckles or no freckles; and so on and so forth.)

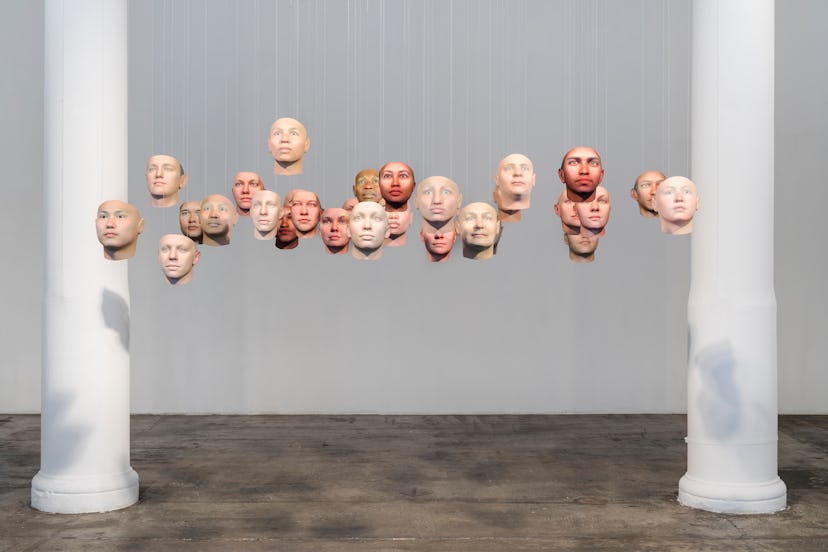

The resulting 30 faces Dewey-Hagborg chose now make up “A Becoming Resemblance,” the Fridman Gallery exhibition that, for the most part of its making, was actually just a dream. In 2016, Manning’s already brutal time in custody took a turn for the worse: She tried to kill herself, was sentenced to solitary confinement, tried to kill herself again, and went on hunger strike to protest her mistreatment and the mishandling of her gender dysphoria (which she ended when the military granted her request for gender transition surgery). “At that point, obviously I was really worried about her, and I was trying to send positive messages however I could,” Dewey-Hagborg said.

Installation view of “A Becoming Resemblance,” 2017, at Fridman Gallery.

And, with President Obama’s term coming to an end then, she also made a plan: Working with the illustrator Shoili Kanungo, Dewey-Hagborg and Manning set about creating a comic book envisioning Obama commuting Manning’s sentence, and a freed Manning visiting an exhibition of her portraits in-person. The resulting book, Suppressed Images, was published three days before the end of Obama’s term, on the morning of January 17, 2017—the same day that, a matter of hours later, Manning ended up being freed. “I have no idea if Obama actually saw [the book], but it felt like magic,” Dewey-Hagborg recalled.

Last week, Manning did indeed get to visit the exhibition, whose mission to illuminate the importance of identity issues has only magnified since Manning’s more recent struggles. “It’s about uniting us,” Dewey-Hagborg said. “We’re 99 percent the same on the genomic level, and we’re focusing on that molecular solidarity instead of divisiveness—pointing out that we have so much that brings us together and that connects us.”

Manning is still limiting her contact with reporters, but that didn’t keep her from accepting hugs and posing for selfies with her admirers, whom Dewey-Hagborg said turned the opening night into “a love fest”—one that the pair definitely seems like they’ll continue themselves, even if that means just sitting in the park or running errands to Home Depot. “It’s so wonderful now that I can just send her a text message,” Dewey-Hagborg said of their friendship. “It’s incredible.”

Related: Chelsea Manning Makes Her Case in First Post-Prison Interview

Meet the Women Who Made History as the Organizers of the Women’s March on Washington: