Every profession boasts one or two figures who, while not always the most prominent or conventionally successful, are generally seen to be exemplars of their type, setting the standard against which colleagues are measured. So we have writer’s writers, like Henry Green and Mavis Gallant; and painter’s painters, like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin and Giorgio Morandi. In the case of fashion, where designers sizzle in and out of neon visibility with heartbreaking frequency, the possibility of being lauded and then discarded is even greater, leaving a long list of figures who are ghostly presences to all but a few connoisseurs. Even in so large a company, however, one man stands out as the fashion designer’s fashion designer—and did so even before his impoverished death in New York’s Chelsea Hotel in 1978—and that is Charles James, the subject of this spring’s retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum’s Anna Wintour Costume Center from May 8 through August 10.

In the 1940s and ’50s, James was admired to the point of adulation for his unerring eye and sui generis approach to construction. Despite the designer’s mercurial moods and disregard for the more practical end of fashion, women of means and discernment sought him out for the way his almost sculptural “shapes” (as he was fond of calling them) transformed their bodies, with the aid of mathematically precise dressmaking techniques that came close to feats of engineering. He formulated his ideas early on and never departed from them: “Cut in dressmaking is like grammar in language,” he observed. “A good design should be like a well-made sentence, and it should only express one idea at a time.”

James was one of the few Anglo-American designers to work in the tradition of classical couture. He was esteemed for the intensity of his creative vision by Christian Dior, who once said that James inspired the New Look; and Cristóbal Balenciaga, who extolled him as “the greatest American couturier.” He’s best remembered for his ball gowns, which were designed over a period of 10 years early in his career and are nothing short of spectacular in their marriage of two of his “cutting trademarks,” as Elizabeth Ann Coleman describes them in her excellent book The Genius of Charles James—“rigid geometrical forms and fluid asymmetrical folds.” This designer—who, by the by, disdained the term “designer,” insisting that “designers are hired help that only copy what is in the wind”—was also known for his genius with outerwear and his virtuosic use of fabric and color. (His color designations alone, including “liver mauve,” “biscuit,” and “bull-tongue,” are worthy of his place in history.) He believed that fashion consisted of “what is rare, correctly proportioned, and, though utterly discreet, libidinous.”

Given all this, one might wonder why James’s reputation as a visionary—he was the first to use spiral draping, with and without zippers; to make coats entirely out of grosgrain ribbons; to use dozens of fresh flowers as adornment; and to dream up a prescient quilted jacket of white satin filled with eiderdown, in 1937—had begun to fade by the ’60s, and why his business career was such a consistently checkered one. The answer lies in part with James’s thinking, which was genuinely avant la lettre on many fronts, and in larger part with his frequently self-destructive personality. A nonconformist who respected few dictates except those devised to satisfy his own requirements, he also had the ornery pride and willfulness of an autodidact. Although no one is entirely clear on exactly when and how he acquired his fashion smarts, Coleman has him going to Paris to “educate himself in line, fabric, and construction” in 1932. What is incontestable is that from his earliest years he seems to have alienated as many people as he enthralled; a lifelong friend remembered meeting the 13-year-old James and finding him an “obnoxious little boy.”

In thinking about James, it’s important to keep in mind that, his considerable intellect notwithstanding, he was, first and foremost, an aesthetic and social snob. “His dream,” according to Halston, who was a protégé and admirer, “was to dress the best in the world,” and at the height of his renown during the late ’40s and early ’50s, James did, indeed, dress the women who were the acknowledged tastemakers of their time, such as Millicent Rogers, Austine Hearst, Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, and Babe Paley. James’s concern with fit was such that in 1949 he went to the trouble of creating a new, more elongated dress form with a dipped waistline and repositioned armholes that he thought more closely followed the contours of the women he dressed. In 1954, he introduced a loose-fitting silhouette based on his observation that “women don’t get fat all over, usually just in front.” Still, his elaborately seamed and darted clothes were made in the main for slender socialites; according to the recollections of Anne, Countess of Rosse, one of his celebrated clients from the ’30s, he was not above dismissing frumpier types who sought him out—no matter how rich—with a few cruel words.

James remained something of an enfant terrible throughout his life—a persnickety perfectionist who thought nothing of ripping apart a dress and starting afresh or of failing to deliver altogether on a promised gown. He built a flexible foam rubber model to study the effects of movement on a shape and reportedly spent three years and $20,000 on a quest to achieve a smooth sleeve.

Far from being a shrinking violet, James had a yen for self-promotion that matched his artistic aspirations. Well before anyone had heard of branding or licensing, he sought out ways to mass-market his designs and to emblazon his name in the minds of fashion editors and potential customers. “My name,” he said, “is my capital.” His passion for self-documentation led him to devise ways for his clothes to be donated to institutions; he engineered the single biggest gift of his work, to the Brooklyn Museum, by Millicent Rogers, which resulted in his first retrospective, “A Decade of Design,” in 1948. Charles James was born in England in 1906, the middle child of a British father, who was a captain in the military, and a wealthy American mother, and brought up in Edwardian luxury. He was given a traditional upper-class education until his expulsion from Harrow for what he called a “sexual escapade” (he was openly homosexual from his late teens on). School friends included Evelyn Waugh and Cecil Beaton, who became a staunch supporter of James’s, introducing him to influential people and photographing his creations. At 19, after a very brief stint working for a friend of his father’s in Chicago, where his parents had moved, and at the Chicago Herald-Examiner, James opened a millinery shop. Although he had a fraught relationship with his father, who prohibited his wife and daughters from frequenting James’s establishment, his clients were often well-connected friends of his mother’s.

By 1928, James had moved on to designing clothes—his first customers included such Jazz Age stars as the English actress Gertrude Lawrence and the legendary performer Gypsy Rose Lee—and 1929 saw the first mention of a James millinery confection (a blue felt hat under the name Boucheron) in American Vogue. In 1930 he sold custom hats and dresses at a New York shop co-owned by a Standard Oil heiress and entered into a fairly unprecedented arrangement with the retailer Best & Co. to sell both copies (costing $17.50) and originals ($35) of his hats. In that same year, prefiguring his many short-lived business ventures, he opened a London outpost; it went bankrupt quickly and the designer, ever the contrarian, threw a lavish party.

James traveled between Paris and London for much of the ’30s; Virginia Woolf dropped his name in a letter to her friend Vita Sackville-West in 1933: “So geometrical is Charlie James that if a stitch is crooked…the whole dress is torn to shreds,” Woolf wrote.

In the two decades that followed, in between running from creditors, James created wave after wave of excitement with his inventive designs, garnering kudos from the likes of Paul Poiret (“I pass you my crown; wear it well,” Poiret told James after his first Paris showing, in 1937) and honors in Europe as well as America. Although by 1948 he considered himself the highest-paid fashion designer in the world, money seems to have run through his fingers—despite his sometimes eyebrow-raising financial schemes (at least one of which came under the scrutiny of the IRS). The truth of the matter is that James, much as he clamored for press coverage and profits, was always more of a lone-wolf artist than a company man. He didn’t work well with others, and he resolutely failed to keep an eye on the bottom line. (In 1949, he estimated that he’d spent between $1,000 and $3,000 to make a custom suit that sold for $800.) He continued to actively design into the late ’50s, introducing a line of infants’ wear after surprising everyone by marrying Nancy Lee Gregory in 1954 and having two children. But by 1958, his business setbacks had caught up with him and he bounced from one temporary residence to the next. In 1964, divorced, James moved into the Chelsea Hotel, where he remained until his death in 1978. He taught students both formally and informally up to the end—and never stopped experimenting with muslins and patterns.

It would be nice to think that James would be made deeply happy by this latest and most complete round of tributes; in addition to the Met show, “A Thin Wall of Air: Charles James” opens at the Menil Collection in Houston on May 31 (through September 7). But the fact that his designs live on would no doubt have struck this fiercely egotistical and demanding man as no less than his just due.

Photos: King Charles

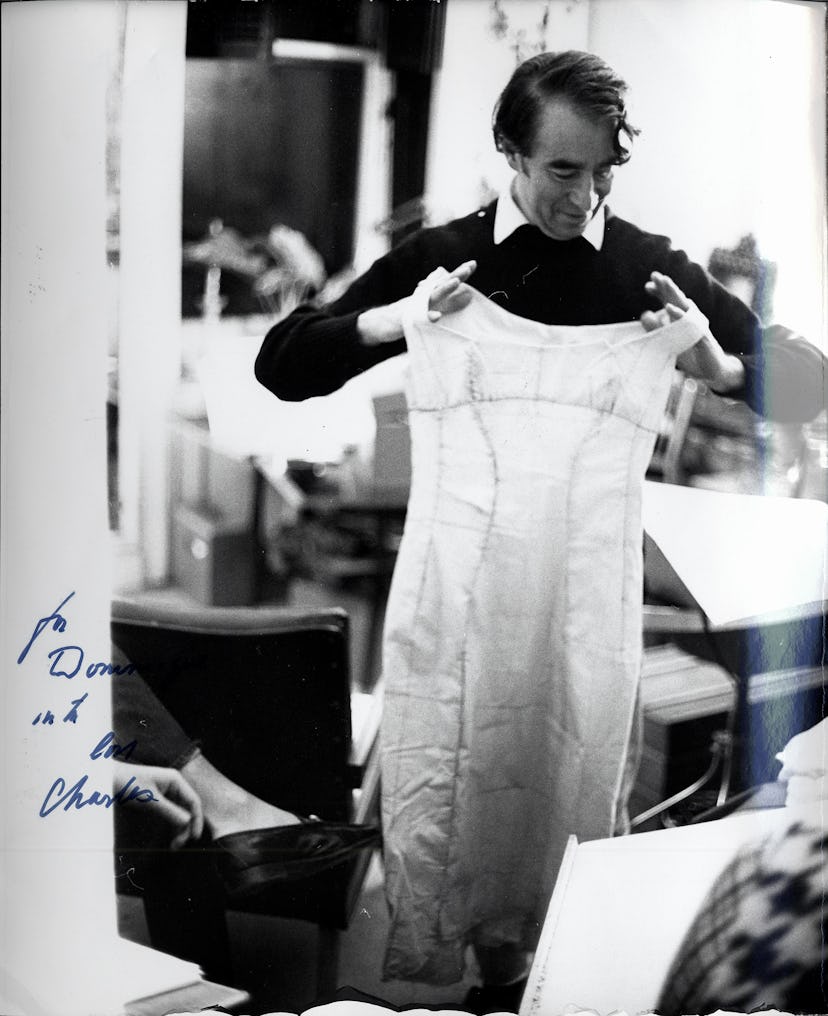

Inscribed photograph of Charles James holding a dress lining, n.d. Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston Courtesy of Charles B.H. James and Louise D.B. James.

A draped James gown from 1955. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009.

A 1950 show. Courtesy of the Menil Archives, Houston/Charles James Jr. and Louise James.

Antonio Lopez’s illustration of a 1968 look. Courtesy of Galerie Chariau-Bartsch.

A 1954 “butterfly” gown. Courtesy of Getty Images.

A ball gown from 1949–1950. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

James, with models at a 1950 show. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art; © Bettmann/Corbis.

A 1973 illustration by Lopez. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photograph by John Rawlings, Rawlings/Vogue/Condé Nast Archive.

A 1951 evening gown. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A fitting in 1948. Courtesy of Getty Images.

A 1956 sheath dress and suit. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

A “four leaf clover” evening dress from 1953. Courtesy of Art Resource.

Austine Hearst in the same gown. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photograph by Cecil Beaton, Beaton/Vogue/Condé Nast Archive. Copyright © Condé Nast.

Babe Paley in a crimson James gown, 1950. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Elizabeth Fairall, 1953.