Carrie Mae Weems Reflects on Her Seminal, Enduring Kitchen Table Series

“I knew what it meant for me, but I didn’t know what it would mean historically,” the artist says of her now iconic photographs.

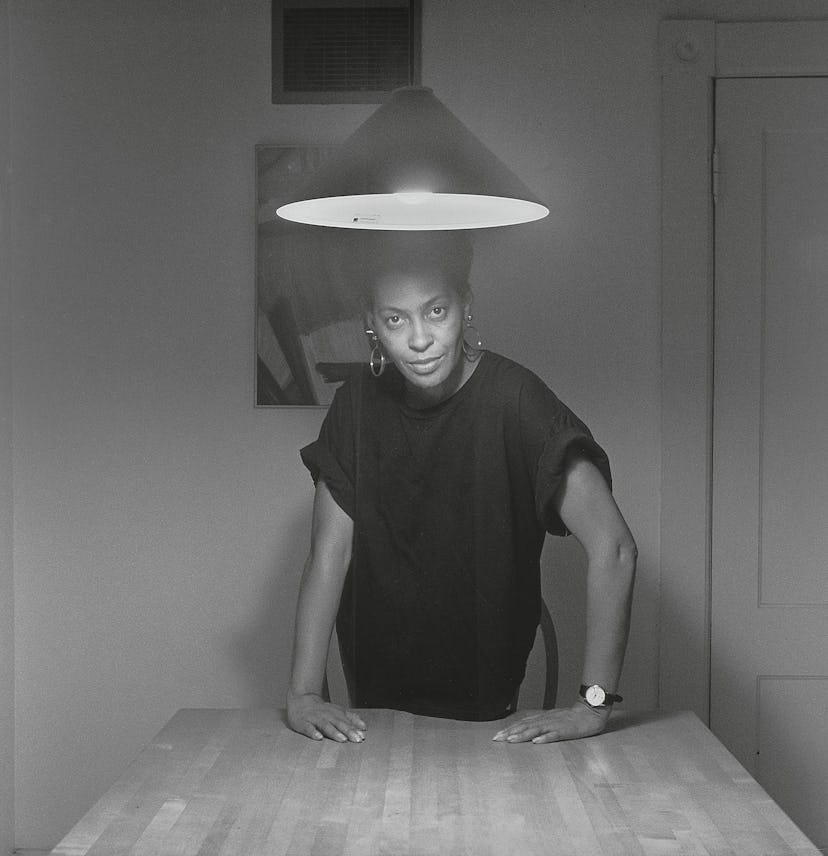

Decades ago in Northampton, Massachusetts, Carrie Mae Weems began devoting a part of every single day to photographing herself at her kitchen table. Obsessive in telling the story of the woman she was playing—whom we follow through the course of relationships with her lover, her friends, and her daughter—Weems knew the series would be important to her. She didn’t realize, though, that it would take on historical significance, too, paving the way for a generation of women artists concerned with their own representation, as well as in conversations of race and relationships to boot. Since then, Weems has landed a MacArthur “genius grant” and around 50 solo shows, including the Guggenheim’s first retrospective of an African-American woman. And her Kitchen Table Series has been equally enduring, making its way into plenty of books and museums over the years. It’s now finally getting a stand-alone copy, out at the end of April from Damiani. Here, Weems reflects on why it’s as relevant as ever.

How do you feel about this series now, over 30 years on? It’s interesting. I started working on it in like 1989 and I finished it in 1990, so it’s been around for a long time. I really do think of it as a seminal body of work—it was the coming together of many, many, many sorts of stops and starts and trials and errors, just that sort of struggle of a young artist to discover the nuance of my own voice, my own photographic style, my own vocal utterance. All those things came together in this piece. I still find it remarkable, and I’m still completely surprised by it, and how it’s still so completely contemporary. It’s very difficult to discern when the work was made; it could have been made 30 years ago, or it could have been made 30 days ago. The sense of time is really displaced within the work. At least I think that that’s true.

Revisit Carrie Mae Weems’ Enduring Kitchen Table Series

“Untitled (Man and mirror)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Eating lobster)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Man reading newspaper)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Woman and phone)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Woman with friends)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Woman brushing hair)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Woman and daughter with makeup)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Woman with daughter)” (© Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Woman and daughter with children)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Woman standing alone)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Nude)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Untitled (Woman playing solitaire)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Did you have a sense that it was going to be such a seminal work at the time? No, but I knew that it was important for me. I worked on it constantly, every single day for months and months and months. I knew that I was making images unlike anything I had seen before, but I didn’t know what that would mean. I knew what it meant for me, but I didn’t know what it would mean historically, within the terms of a graphic history.

It started with you trying to create images you thought didn’t exist at that point—ones that properly represented women, and black women in particular. Would you say that those images now exist today? Oh yes, I think there are certainly more women known to us who are making important and seminal work focused on the dynamic and complex lives of women. People like Mickalene Thomas, Cindy Sherman, and Lorna Simpson have come along, and all of us sort of stand in a line, marking a trajectory that’s deeply concerned with the constructed image and representation of the female subject. Yet I think the [Kitchen Table] images are more current now than ever before, and I’m still very much aware of the ways in which women are discounted: They’re undervalued within the world generally, and within the art world in particular. And of course that was something that came up with the Academy Awards this year, right? There’s still sort of a dearth, a lack of representational images of women. And not, you know, like strong, powerful, and capable, that kind of bullshit, but rather just images of black women in the world, in the domain of popular culture. I think it’s one of the reasons that Kitchen Table still proves to be so valuable, or invaluable, to so many women, and not just black women, but white women and Asian women; and not just women, but men as well, have really come to me about the importance of this work in their lives. I find it remarkable.

Why did you originally decide to put yourself in the photos, since the series wasn’t specifically about you? Because I was the only person around. It really is true. I work often and a lot, and in this case, sometimes I would work at six in the morning or three in the afternoon. I was just simply available. I began to understand, too, that I’m very interested in the performative, and that’s one of the things that the work has actually taught me. I use my body as a landscape to explore the complex realities of the lives of women.

“Untitled (Man reading newspaper)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Do you still keep in touch with the others in the photos? No, not really. It was so many years ago. They were my neighbors, people that I found on the street. The little girl that’s on the cover—I don’t remember her name anymore, though it’s probably in my files—I saw her one day chasing a boy on a bicycle, I think. I thought, ‘There’s my girl, there she is.’ And she looks like me, she looks like she could be my daughter. Some of them are friends and some of them are colleagues, all living in Northampton, Massachusetts, which is where the work was made. I go back, maybe once a year or something like that. The apartment isn’t there anymore, but I do have friends in the area.

The series is most known for its black-and-white photos, but there’s a large text component, too. How do you see the relationship between the two? I added the text just as I was wrapping up, and it was wonderful. A man had come to visit me, and we had this wonderful talk about men and women, about our relationships, and he left and then I took a long drive. I always drive with my tape recorder, and I started reciting this text. By the time I got home, it was done, and I went upstairs to my computer and transcribed it. But you know, I’ve always thought that both the photographs and text operate quite independently, and together they form yet a third thing, something that is dynamic and complex and allows you to read something else about the photographs. I don’t think of them as being necessarily dependent on one another. Rather, they exist side by side, in tandem.

Would you say that the series is as much about black representation as it is about women? I think it’s important in relationship to black experience, but it’s not about race. It’s not the thing that’s foremost important about the work at all. But I think it can be used in that way, for sure.

“Untitled (Woman and daughter with children)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Do you think it’s been interpreted as the main point of the work? Well yes, because I think that most work that’s made by black artists is considered to be about blackness. [Laughs.] Unlike work that’s made by white artists, which is assumed to be universal at its core. I really sort of claimed the same space, and I think the work in many ways is universal at its core, but we can certainly also use it to talk about the position of black representation. That was not the intent of making the work, but it can function in that way, and to talk about how photographs are constructed, since it uses the tropes of documentary but in highly constructed, staged images. We can use it to talk about the relationships between men and women, women and children, women and women, and to have large discussions about the issue of the representations of blacks and their relationships. Maybe that’s one of the reasons why the work has sort of stood the test of time and entered the culture in this unique way: You can use it to have many, many kinds of discussions about things that are going on in the world today. You know, we know that for the most part the work that’s made by women is simply not valued in the same way as work that’s made by men. It just isn’t, and it’s something that we have to struggle against consistently, persistently, if we want to see change in that area. I’m looking forward to a leveling of the playing field.

Have you found your treatment as an artist has gotten better? You’ve definitely found some mainstream success along the way. No. I mean of course, you know, I’m acknowledged, I’m offered awards, and those kinds of things, they’re really wonderful. But I’m aware of what it means not to have the work valued seriously, so that you’re always struggling for a fair price for the work, that you have to fight for that.

“Untitled (Woman and phone)” © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

So you’re saying that you still feel like you have to struggle? Absolutely, I do. And that I’m aware that I have to. And you know, from my perspective, I do this not simply for me, but I do it for the larger cause of equality, that I’m interested in all aspects of equality, and when I feel as though women through my own experience are not being taken as seriously as others, then I think it’s necessary to speak up. I’m not always the most popular girl in the room [laughs], but I think that it’s important.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Related: Mary J. Blige and Carrie Mae Weems in Conversation, on Race, Women, Music and the Future

Strength of a Woman: Mary J. Blige Photographed By Carrie Mae Weems

Mary J. Blige wears an Alberta Ferretti cape; Joseph coat; Djula earrings; vintage crown from Early Halloween, New York.

Mary J. Blige wears an Alberta Ferretti cape; Joseph coat; Djula earrings; vintage crown from Early Halloween, New York.

Pologeorgis coat; Gucci jacket; Fred Leighton tiara and necklace; stylist’s own earrings.

Balmain dress; Jacob & Co. earrings; Munnu the Gem Palace ring.

Oscar de la Renta dress; Djula earrings; (right hand, top) Vhernier ring; David Webb rings. Carrie Mae Weems wears her own clothing and jewelry.

First column from top: Alberta Ferretti cape; Joseph coat. Balmain dress. Third column: Oscar de la Renta dress. Tom Ford dress. Fifth column: Oscar de la Renta dress. Oscar de la Renta dress; Tom Ford coat.