I had never felt like a woman until I got strong. My body was ruler-shaped—a long, lean assemblage of straight planes; flat in front and back—and though I dressed gamine, in 1960s micro-minis and shrunken V-necks, that classification never quite fit. My shoulders were too broad to be waifish, I’d lament, and real waifs had waists. At 35, I still occupied my figure tentatively, maintaining it diligently and dressing it well but never fully feeling at home.

All that changed when I met Adam Ticknor, a Texan Marine sniper–turned–strength trainer. Adam rolled into my subdued Los Angeles neighborhood in a Ford F-250 loaded with sinister-looking kettlebells and stacks of barbell plates. That was nine years ago, at a time when skinny girls like me typically stuck to running, yoga, and Pilates. Adam, who briefly became my boyfriend and then, more lastingly, my coach, sized up my ectomorph physique with his penetrating sharpshooter’s vision. “You’d look hot with 10 to 15 more pounds of muscle on your body,” he said.

This was a shocking proposition. Of all the goals I’d been advised to pursue in the course of my life, getting bigger was not one of them. But it was also intriguing. Adam taught disaster preparedness in addition to fitness and believed that a healthy human body was one that could safely perform all “the basic tribal functions,” like pushing things, pulling things, and moving efficiently across rough terrain under a load. My ability to scamper, whippet-like, up L.A.’s steep canyon trails with a water bottle, or perform twisty asanas in a climate-controlled studio did not exactly qualify. “Could you pull yourself over a wall to get out of harm’s way?” he asked, playing out a hypothetical scenario in which L.A. was struck by the Big One. “Or squat down, scoop up two kids, and move everyone to safety without hurting yourself?” These sorts of essential human actions required a denser and more developed body— one built on a “posterior chain” of powerful glutes and hamstrings; a solid, integrated trunk, and stable joints able to support me.

Seen through this lens of survival, and living as I did on an active fault line, it suddenly seemed irresponsible to exist in my flyaway form. My whole girlish identity began to shift. A dormant, more forceful femme lay waiting to be unearthed. Adam declared, “Clothes look good on thin people; naked looks good on fit people.” And so Project Waif-to-Woman began.

My training program was structured like a pyramid. Adam explained that the foundational slab of a strong and stable body required quality nutrition and rest—not only ample sleep but also recovery time between workouts. The next layer was education: rediscovering correct movement patterns like squatting and lunging that had been distorted by a non-tribal, deskbound life. The thick, middle strata was stripped-down strength training focused on moves that recruit the major muscle groups of the body, like the dead lift and squats with a kettlebell. Only when these elements had been mastered could I tackle the apex of the pyramid: short and exhilarating high-octane drills involving speed ropes for jumping, sledgehammers for slamming, and monster-truck tires for dragging.

Going from skinny to strong cracked open my deepest vulnerabilities. One day, faced with a loaded barbell, a wave of resistance and fragility brought me to tears. “I don’t know the reason I’m crying,” I sniffled. “Well, if you did know, what would it be?” Adam asked. I’d always stayed in a zone of moderate exertion, and stepping beyond that brought up an ancient dread: “I’m scared I don’t have it in me,” I replied. But the only way through that fear was to become comfortable with discomfort. “Short bouts of controlled duress will amplify everything good in your life,” Adam promised. He was right. Lifting my way through discomfort zones triggered my brain to release natural chemicals that helped me think more lucidly. My hormones self-regulated, and my sex drive increased. At night, I’d fall into a deep and dream-filled sleep.

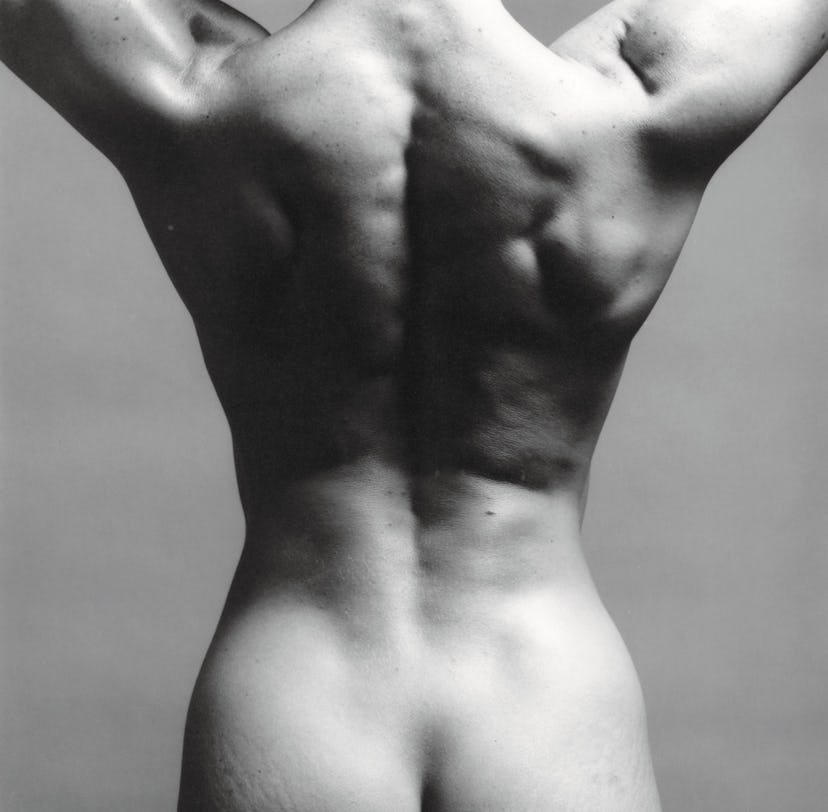

*Lisa Lyon*, 1982, by Robert Mapplethorpe

About five months into this regimen, I looked at myself naked and was completely taken aback. My angular lines had given way to the wondrously unfamiliar phenomenon of shape. My small breasts had become fuller, supported by developed back muscles. My solid trunk curved inward at the waist, and my shoulders were contoured, not blocky. When I turned around, I discovered a defined, rounded butt. I felt a reverent kind of pride in the pounds of muscle I’d put on—10 total, at my peak—and in the new outline I’d created. It represented a woman who was finally inhabiting herself fully. When I met my husband three years into my new lifestyle and became pregnant, I carried our daughter comfortably for almost 42 weeks. Then, when the intensity of birth escalated in a second and my midwife commanded me to deliver my child “right now,” a memory of my heaviest dead lift surged from my unconscious; I mightily pushed our baby into the world. Motherhood is an experience of dissolution, a blurring of edges as your life merges with that of your child. Sapped of energy and free time, I put my weights into storage. But as one year became two, and the mundane pressures of marriage and money tugged at my core, I became increasingly fragmented and flighty in the face of challenge. When my strength diminished, my enhanced functionality went with it, just when I needed it most.

In Chinese medicine, it’s said that when the child turns 3, the mother gets half of her chi back. Half would do. I called Adam, hoping he’d tell me to pick up where I’d left off. The fitness landscape had proliferated with intense training programs, and I was hungry for the clarifying rush of heavy lifting. But my mentor commanded that I delay gratification. “Slow your roll: quality first, intensity later.” Leaping into aggressive workouts like the wildly popular CrossFit would put too much wear-and-tear on my deconditioned body and possibly land me in the hands of an overzealous coach.

Following the precept of “prehab today, not rehab tomorrow,” I met with Brianna Battles, a postpartum fitness expert in Thousand Oaks, California. She assessed me for pelvic-floor and abdominal-wall integrity, a must for mothers returning to training, and taught me the posture-and-breath technique necessary for maintaining correct intra-abdominal pressure during movement. My backward-leaning, hips-forward stance—the classic mother’s carriage—was undermining me, Battles said. She stacked me straight; immediately, I felt closer to my power.

Then Adam gave me my prescription for the year ahead: gymnastics strength training. “Build the little meat before the big meat,” he said, referring to the connective tissue of tendons and ligaments that hold muscles and bones together that are typically neglected in training, making them a major liability—easy to injure, hard to repair. I enrolled in GymnasticBodies, an online training system with a linear progression of exercises built around challenging stretching sessions and seven fundamental gymnastics moves. I have never envied the compact, powerhouse physiques of gymnasts or the unbelievable flexibility they possess. But now, as I diligently attempt to open my shoulders and arch my upper spine into a stable bridge, I’m humbled by how much of my body’s range I’d never accessed. Gymnasts aren’t inhuman—they’ve mastered human movement that most of us don’t use.

I’m three months into my new project of building the body that I will inhabit for the next 40-plus years. As soon as my remodeled foundation feels solid, I will seek out a local coach certified by StrongFirst—a training system developed by the Russian strength guru Pavel Tsatsouline—to relearn solid barbell and kettlebell skills, and build power and mass. In 12 months, Adam predicts, I’ll be able to crush whatever fitness program I choose. I’m thinking this might not involve a sweaty gym at all but, rather, primal-movement practices from MovNat, Ido Portal, or Animal Flow, which develop the stability, mobility, and strength required for thrilling movement and play outside. It turns out that my daughter is an agile little warrior who’s most in her element climbing craggy boulders in our nearby forest. I just want to be able to keep up with her.

Watch W’s most popular videos here: