A Night at the Brooklyn Museum’s Studio 54 Exhibition (Before It Closed)

Before the Brooklyn Museum closed indefinitely, a last chance to experience Studio 54's enduring power.

If you’ve ever been to a truly incredible nightclub, you know the feeling: that unique rush of adrenaline and euphoria you get when an intimidating doorman grants you entry into another dimension, where music becomes mother nature, and pleasure is our predominant pursuit. There’s an undeniable poetry to an effective dance floor, where sounds shift the atmosphere like the weather, and dancers whirl in flashing lights. As someone on an eternal quest for romanticism after dark, I have all but given up on finding it at a registered address in New York. And while I’ve grown to accept that I’ll never feel that sparkling rush at places like 1OAK or Elsewhere, I did find it this week—at, of all places, the Brooklyn Museum.

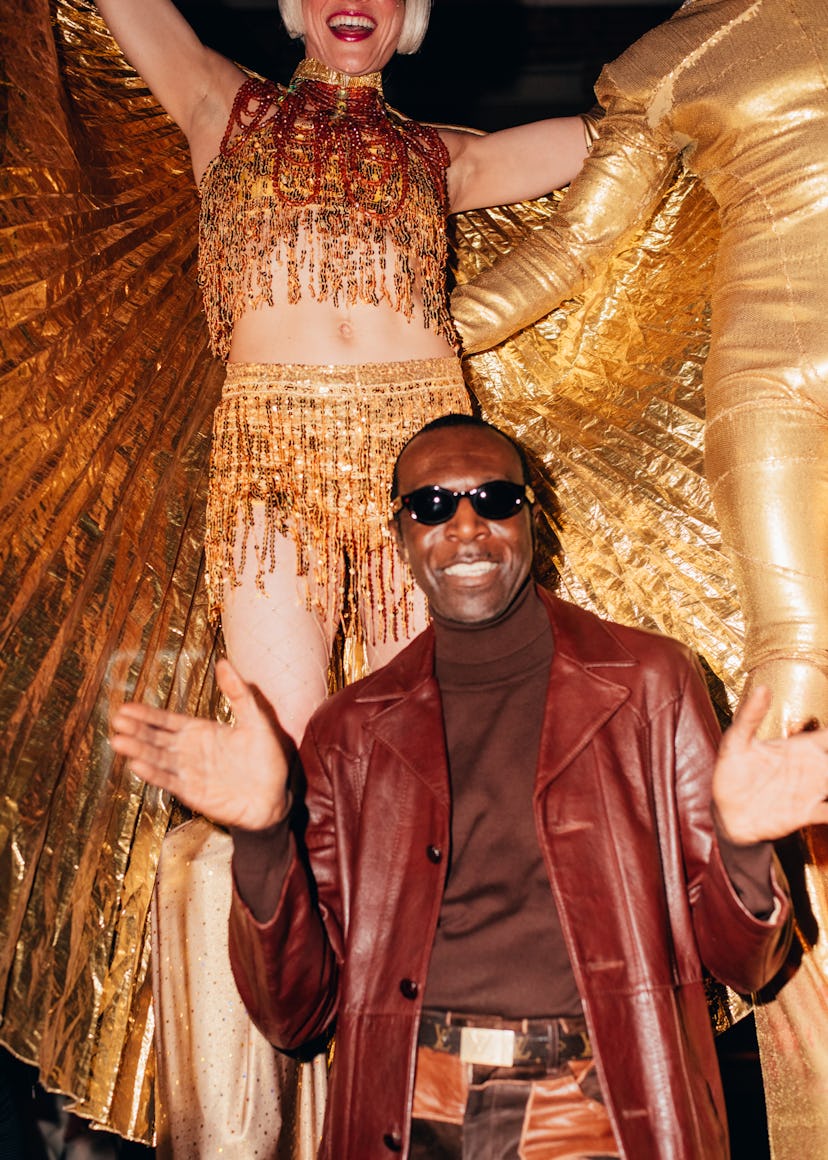

Scenes from the Brooklyn Museum’s Opening Reception for “Studio 54: Night Magic,” on March 11, 2020. Photographed by Timothy O’Connell for W magazine.

“Boogie Nights” was blasting as I walked into the Museum’s opening party for its “Studio 54: Night Magic” exhibition, which considers the artistic impact of the most famous club in the city’s history (and, arguably, of all time). In what is typically a stark lobby, tinsel streamers rained gold onto a dance floor filled with drag queens and art aficionados. Performers Rollerbladed around costumed stilt walkers, as attendees shimmied with glasses of champagne. The official dress code for this event? “Fabulous.” People in rainbow, sequined pantsuits, and white feathered capes danced with joyful abandon. The celebration far exceeded the few expectations I had for a party during a pandemic, when glamour and fun are among the first depleted resources.

The glittering guests enjoying their “Last Dance” with Donna Summer didn’t yet know that this would also serve as a going away party. The Brooklyn Museum announced its coronavirus-related closure less than 48 hours later, on the day that “Studio 54: Night Magic” was set to open. While its reopening date is uncertain, the uplifting show will certainly strike a chord when it’s back on view. The expansive exhibition is a tribute to the art of dancing through dire consequences, which feels more relevant than ever.

Scenes from the Brooklyn Museum’s Opening Reception for “Studio 54: Night Magic,” on March 11, 2020. Photographed by Timothy O’Connell for W magazine.

Studio 54 first opened in 1977, thanks to the combined vision and ambition of two friends: Steve Rubell, who passed away in 1989, and Ian Schrager, who is now perhaps best known as a hotelier. Together they acquired a property on West 54th street that had lived past lives as an opera house and a CBS television studio. With the help of an inspired team of creatives, they converted the space into a discotheque in under six weeks. Rubell and Schrager did everything in their power to harness the unique assets of the venue, and in doing so, engineered a clubbing experience that was animated by drama and stagecraft. The exhibition text reads: “The exhilarating combination of high-end interior design, the original theater architecture, and changing, state-of-the-art sets, lighting, and sound created a sophisticated, often surprising environment that had never before been experienced in a New York nightclub.” With help from Tony Award–winning lighting designers, Rubell and Schrager turned a stage into a dance floor that made everyone feel like a star.

Scenes from the Brooklyn Museum’s Opening Reception for “Studio 54: Night Magic,” on March 11, 2020. Photographed by Timothy O’Connell for W magazine.

The cinematic atmosphere encouraged a culture of performance, experimentation, and unapologetic debauchery. In its 33-month run, Studio 54 became a world-famous celebrity hot spot, known for its restrictive door policy, queer inclusivity, and anything goes approach to drugs and sex. It boasts a ridiculous list of famous patrons that includes Cher, Salvador Dalí, Calvin Klein, Al Pacino, and Truman Capote. Thanks, in part, to an intimate relationship with tabloids and the press, the club’s prestigious reputation holds up decades later. Then again, Studio 54 was the stuff of legend, from Day One. The formidable case of tax evasion that landed Rubell and Schrager in prison and forced the venue to shutter its doors in 1980 seems to have been pardoned in our historical memory. Mention Studio 54 to someone on the street and they’ll more than likely talk about disco, cocaine, or Andy Warhol—all of which helped secure Studio 54’s role as a cornerstone of the 1970s cultural landscape.

Scenes from the Brooklyn Museum’s Opening Reception for “Studio 54: Night Magic,” on March 11, 2020. Photographed by Timothy O’Connell for W magazine.

The Brooklyn Museum curator Matthew Yokobosky made incredible efforts to re-create the “night magic” that came to define Studio 54. “I had never seen an exhibition done about one nightclub before,” Yokobosky said. “So, the big question for me was, How do you bring a sense of place into a museum? How do you give a gallery the sense of a nightclub?” The exhibition’s evening atmosphere is enhanced by the Brooklyn Museum’s own take on kinetic lighting, and a disco soundtrack that changes in each gallery.

It took Yokobosky two years and over 100 interviews to acquire the 650 different objects on display. The chronological show includes virtually every medium: photography, fashion, drawing, film, set proposals and architectural designs, and more. In having catered to a predominately creative clientele, the traceable repercussions of Studio 54—in ethos, aesthetic, sound, and design feel endless.

Scenes from the Brooklyn Museum’s Opening Reception for “Studio 54: Night Magic,” on March 11, 2020. Photographed by Timothy O’Connell for W magazine.

Visitors can expect plenty of drool-worthy Studio 54 ephemera, like invitations, coat check tags, logo mock-ups, and guest lists. Among the more storied artifacts: a bundle of drink tickets that Rubell gave to Warhol for his birthday, Pat Cleveland’s original clubbing clothes, and a 62-carat sapphire that Elizabeth Taylor once sported at the venue. Other highlights include the artistic byproducts of Studio 54’s enthusiastic drug culture, which is immortalized in Richard Bernstein’s poppers wallpaper and the club’s iconic moon and spoon set piece. The exhibition’s wall text explains the imagery in comically matter-of-fact language: “Several times a night at Studio 54, a moon and a spoon would fly in separately from the left and right wings and meet center stage. The spoon would then twinkle and a line of lights would zip up the moon’s nose, referring to the use of cocaine.”

The show addresses the club’s predecessors and its afterlife in inventive ways. The entrance to the exhibit, which is designed to mirror the actual entrance of Studio 54, leads to a dark room that’s dedicated to the earlier history of New York nightlife. Here, there’s an impressive collection of 20th-century glass- and silverware (think martini shakers from the ’20s). Toward the end of the show, clothing displays surround a manufactured dance floor. Studio 54–related designs from the ’70s stand beside modern interpretations by designers like Rick Owens, illustrating the club’s enduring relevance in fashion.

Scenes from the Brooklyn Museum’s Opening Reception for “Studio 54: Night Magic,” on March 11, 2020. Photographed by Timothy O’Connell for W magazine.

While there are a couple of lead acts who dominate the show, like Warhol, Fiorucci, Grace Jones, Bianca Jagger, and Liza Minnelli, there’s also space designated for the club’s unsung heroes, like its bartenders and DJs. Yokobosky succeeds in explaining that Studio 54 itself was a work of art, if not a masterpiece, made possible by the contributions of many.

“Studio 54: Night Magic” is a profound rumination on the value of fun, and shows that “unserious” endeavors can usher in positive social, cultural, and financial change. Studio 54 played a significant role in rebranding New York after an economic depression; it brought vibrancy and positivity back to a nearly bankrupt city, following years of protest and upheaval. After the trauma of the Vietnam War, it offered New Yorkers a venue for artistic, sexual, and physical expression, and provided space for people of various walks of life to come together in celebration. Truman Capote once spoke of the club on The David Susskind Show: “[Studio 54] is everything the way it ought to be. It’s very democratic. It’s all kinds of colors. All kinds of sizes. Boys and boys together. Girls and girls together. Girls and boys together. Poor people. Rich people. Taxi drivers. Anything you want.” As easy as it is to dismiss hedonistic pursuits, the Brooklyn Museum shows just how far a little glitter can go. The exhibition’s closes with a quote from Liza Minnelli: “Studio 54 brought a glamour back to New York that we haven’t seen since the ’60s—it made New York get dressed up again.”

Scenes from the Brooklyn Museum’s Opening Reception for “Studio 54: Night Magic,” on March 11, 2020. Photographed by Timothy O’Connell for W magazine.

“Studio 54: Night Magic” was originally scheduled to be on view from March 13 to July 5. The Brooklyn Museum is closed until further notice. We will update this post as new information becomes available.