Inside the Obama Portraits Unveiling: Witnessing Visions of Black Power Shake Up a Gallery of White History

We watched along with Shonda Rhimes and Gayle King as Barack and Michelle Obama were inducted into an entirely white art history.

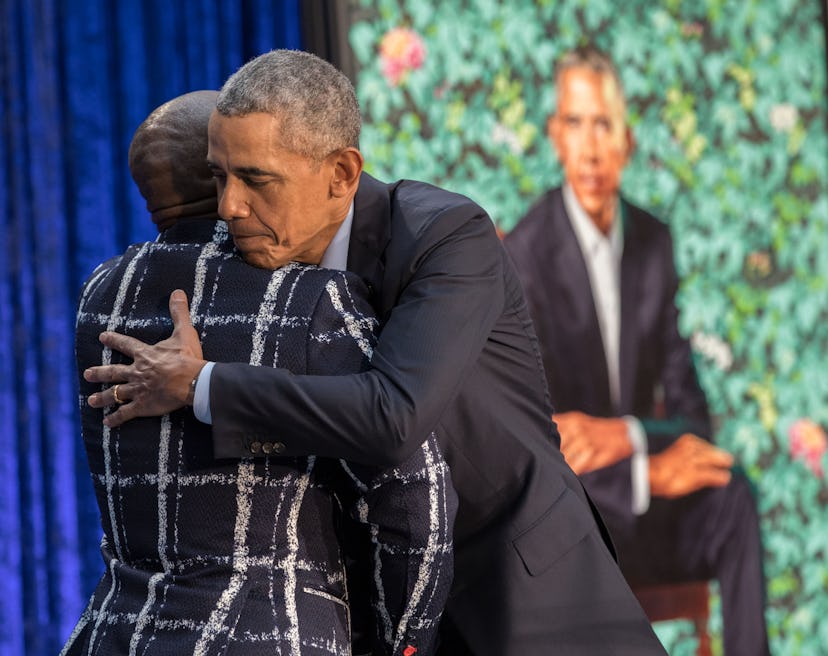

On Monday in Washington, D.C., at 10 o’clock in the morning, audible gasps filled the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery as former President and First Lady Barack and Michelle Obama, along with the black artists they handpicked to paint their likenesses, Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, respectively, unveiled the former first couple’s official portraits. The artists and the Obamas dramatically tugged at the black cloth that covered the works of art and, as the coverings fell to the floor, what appeared were two images that add another layer to the black journey in America. They are like nothing currently hanging in the National Portrait Gallery and are unlike anything we have seen in the history of portraiture of power in America. The images are conceptually bold and undeniably black, blending together fact and fiction. They will help illuminate in the annals of history the Obama era forever.

Kehinde Wiley’s portrait has Barack Obama in a black suit and a tieless white collared shirt, sitting in a chair in a garden of green bushes and flowers: chrysanthemums, the official flower of Chicago where he began his political career; jasmines, to evoke the Hawaii of his childhood; and African blue lilies, which symbolize the 44th president’s Kenyan heritage. He sits in a chair with his arms crossed over his lap, recalling George Peter Alexander Healy’s arresting 19th-century portrait of Abraham Lincoln (who also began his political career in Illinois), on view in the museum’s permanent “America’s Presidents” galleries. The picture of the first black American president does have an obvious reference point in art history except to call out its overwhelmingly white and male and occasionally ridiculous past. (Case in point: The official portrait of a pixelated Bill Clinton painted by artist Chuck Close that hangs in the presidents gallery—a picture of one white man who abused his power, painted by another.)

President Barack Obama’s portrait by Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

In a distinct way, the Barack Obama portrait is a game-changing departure for the artist, art, and the museum, seeing as Wiley’s subject is a real black man who has enjoyed enormous celebration and distinction as the president of the United States of America. Wiley, who is typically known for conferring on black mothers and daughters and fathers and sons the dignity and the spotlight they deserve, did not have to invent such a scenario on canvas when it came to Obama. The former president himself alluded to it during the ceremony: “Kehinde’s art often take ordinary people and elevate them, lifts them up, and puts them in these fairly elaborate settings,” Obama said. “His initial impulse maybe was to also elevate me and put me in these settings with partridges, spectres, thrones, and shift robes, mounting me on horses!” The crowd laughed. “I had to explain, ‘I got enough political problems without you making me look like Napoleon! You gotta bring it down just a touch.’”

What Wiley did was use the historic presidency as a starting point for what he called “a meta-narrative,” he explained as we stood in the galleries where his painting of Obama will hang: “The landscape and figure obviously has a lot to do with each other as we have fashioned the white male patriarchal figure as the foreground, dominant, present figure of portrait-painting traditionally,” he said. So in painting Obama, Wiley needed a new language and landscape to define a new kind of leader. In the portrait, Wiley removes the obvious trappings of the presidential office that has for the entire lifespan of this country been synonymous with white male power and privilege. Gone are the heavy drapes, the staid gray suits, the oval office, and the White House itself. It focuses your attention on the man and how he remade the office.

“We have done away with that landscape,” Wiley said, “and we have dropped in this sort of jungle, where one becomes dislocated from gravity and narrative, re-fertilized with elements of [President’s Obama’s] own narrative, literally blooming his presence into being.” The portrait is a fresh new vision: A black president in a garden. The irrationality of the image mirrors the journey of a black man becoming the president of a country where his wife’s kin were born slaves. It wasn’t supposed to happen, until it did.

First Lady Michelle Obama’s portrait by Amy Sherald. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Amy Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama also defies the conventions of American history while honoring the black backs who made it possible for the Obamas to occupy the White House, too. The former first lady’s skin is rendered in Sherald’s signature grayscale, masterfully. As President Obama noted, Sherald captured “the grace, beauty, intelligence, charm, and hotness” of his wife. “Let’s face it,” he joked, “Kehinde was working at an disadvantage because his subject was less becoming, not as fly.”

In the painting, Michelle Obama sits in a sea of baby blue, like her husband a world apart from the traditional vision of the White House, wearing a dress by Milly with patterns that alludes to the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian’s abstractions and African American sisterhood. Sherald, snobbing on the stage as she spoke about her work, paid long overdue reverence to the art of quiltmaking by generations of black women and today by Gee’s Bend, the little known African-American female artist collective. Sherald’s portraiture also owes debts to the late photorealistic painter Barkley Hendricks‘ style pictures of black figures removed from circumstance and reset in flat fields of color; Kerry James Marshall‘s early cartoonish self-portraits that redefined contemporary ideas of what constitutes black skin; and yes, Wiley too, who picked up portraiture in the early 2000’s when it was long thought dead and made it cool again. A slew of young black portraitists have followed his lead.

But what sets “Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama” apart is that it’s a history painting of a black woman whose skin is gray. It’s a conceptual play on identity that asks the viewer to see both race and humanity. Mrs. Obama represents what Sherald calls “an ideal” because she is a black woman who became first lady; you can’t separate Michelle Obama’s race from the story, and her startling grayed skin puts that at the center of the narrative.

“I paint black people doing stuff,” Sherald told me, as we sat on a couch in an office at the National Portrait Gallery. “Black women become first ladies. It’s about creating this normalcy through my images,” she said, quoting the photographer Naima Green, who wrote an op-ed in the New York Times about Sherald’s work. The grayscale also accounts for for the fact that, according to Sherald, “Something big has happened in history, something happened that wasn’t supposed to happen and I think they should be represented in that way.” She went on: “She’s so different from any other first lady we have ever had and she needed to be represented differently than any other of the first ladies.”

Rita Wilson and Tom Hanks with Amy Sherald.

When Michelle Obama took to the stage to deliver remarks about her portrait, she said she choose Sherald because of their immediate “sister-girl” connection. She also confessed, “As you may have guessed, I don’t think there is anyone in my family who have had a portrait done.” She said this to a crowd including former Vice President Joe Biden, Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks, and a first few rows of black excellence: Shonda Rhimes, Gayle King, Eric Holder, and the Harlem Museum’s Director Thelma Golden, who advised the Obamas on their selections of artists. The former first lady continued in cool disbelief, “Let alone a portrait that will be hanging in the National Gallery!” It was a sentiment Mr. Obama also telegraphed—“the hope poster by Shep[herd Fairey] was cool but I didn’t sit for it. Nobody in my family tree as far as I can tell had a portrait done.” He added, “I do have my high school yearbook picture which is not great shakes.”

Kim Sajet, the director of the National Portrait Gallery, helped put the Obamas’ personal stories into context: “Portraiture [historically] favored those who could vote—white men who owned land. It was extraordinarily expensive but also for the social elite. You don’t get official portraits of African-Americans, really, until after the advent of photography,” in the 1840’s.

Sherald’s signature palette alludes to this history of photography. “I grew up looking at photographs,” she told me. “My mom had a place where she kept all of her photographs and I would pull them out and I never got tired of staring at these gray pictures of my grandmother.” Sherald said those pictures helped her find herself and black identity in a history of art that had largely left her story out. And now, she and Kehinde Wiley and the Obamas have helped upset history, just enough.

Related: The Obamas and the Inauguration of Black Painting’s New Golden Age In America