The launch event for the artist Anicka Yi’s new fragrance line, Biography, at Dover Street Market in New York was molecular in both content and vibe.

Nourishment was provided by way of petal-strewn Rose Bakery hors d’oeuvres, and in the air, Joel Mainland of the Monell Chemical Senses Center digitally mixed synthetic, “nature-identical” molecules for guests to trial via an olfactometer—a smell synthesizer linked to DJ software.

Scientists and historians of flavor mingled with chefs, scent aficionados, and admirers of Yi’s work. At one point, an artist called Bradley Eros approached Yi, iridescent in a pneumatic Cecilie Bahnsen dress, and offered a folio on his own perfume, eau de cinema, a celluloid-inflected scent of “silver, dust, and light.”

The many fields of practice that converged at the Biography launch—in a fashion space, no less—echo the variable nature of Yi’s practice, which engages with how the senses are, as she notes, always “politically oriented and conditioned.” An extension of her studio practice of the past 10 years, Yi developed Biography with Barnabé Fillion, a perfumer of international caché, who recently moved his principal laboratory from Paris to Mexico, where the varied material palette offers more opportunities for experimentation.

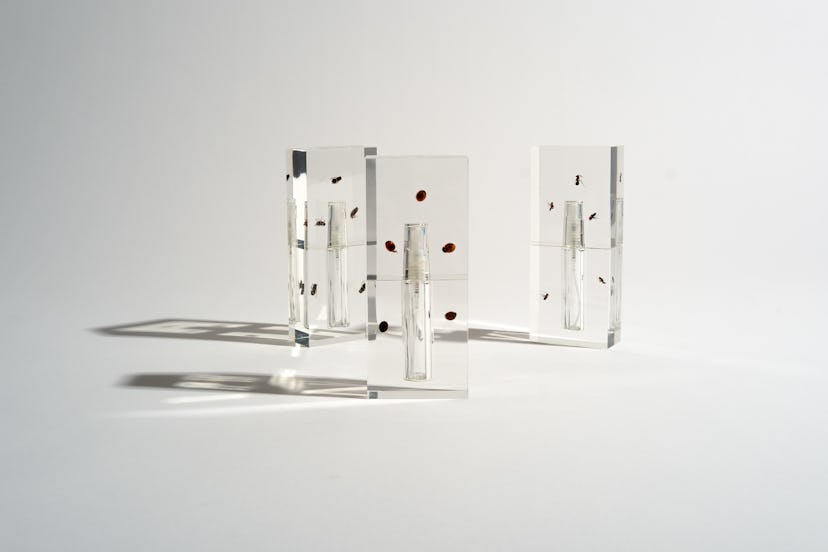

Yi’s Biography comprises three fragrance “volumes,” imagined scent-worlds for different personae, each of which comes suspended in clear acrylic bottles with interior garnishes, like futuristic fossils, of ladybugs, ants, or flies, depending on the scent. “I want to impart an atmosphere of coexistence,” Yi told me, for she thinks of the natural world as “a dizzying template for radical behavior.”

The first “volume,” Shigenobu Twilight, reworks one that Yi developed in 2007 with architect Maggie Peng, and it references Fusako Shigenobu, the long-exiled female leader of the Japanese Red Army via sheer green notes of shiso leaf against rounder ones of black pepper and yuzu. The second, Radical Hopelessness, evokes Hatshepsut, a female pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, through notes of ink, papyrus, and dust—a nod to the evolution of writing systems during the pharaoh’s reign.

The third, Beyond Skin, is propositional (and delicious), designed for a not-yet-existent artificial intelligence entity of the future—yet, interestingly, civet, a mammalian glandular secretion, and red seaweed, provide layered land-and-sea warmth above less emotive tones of burnt plastic, cellophane, and sweat. Beyond Skin grapples with the question of what future “skin” will be, anticipating, as Yi describes, the extent to which technologies of self-augmentation will be absorbed by cosmetics. A “precipice” that is already upon us, she argues.

During the Balenciaga Ready-to-Wear Spring/Summer 2020 fashion show, the artist Sissel Tolaas scented the runway with notes of “antiseptic, blood, money, and petrol.” Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

There is a long lineage of artists experimenting with olfaction, often alongside perfumers, for whom visual expression brings life to a product that is, essentially, invisible: Françoise Gilot once told me that 19th-century Belgian Symbolist Fernand Khnopff would perfume the exhibition space surrounding his paintings. Diana Vreeland pumped fragrance into “The World of Balenciaga” at the Costume Institute in 1973, and philosopher Jean-François Lyotard’s landmark exhibition on postmodernity, Les Immatériaux, at the Centre Pompidou in 1985, included an olfactory installation.

More recently, the artist Sissel Tolaas scented Balenciaga’s spiral runway for Demna Gvasalia’s Spring/Summer 2020 collection, diffusing notes of “antiseptic, blood, money, and petrol” throughout the show. In concept, this was not unlike perfumer Francis Kurkdjian’s 2003 collaboration with Sophie Calle, his first with an artist, on L’odeur de l’argent, the smell of money, which evoked a “well-worn dollar bill” through notes of linen-fiber paper, ink, and dirt.

Kentaro Yamada’s Neanderthal scents, in a hand ax–shaped bottle. Courtesy of Neanderthal.

A more potent foil for Yi’s Biography project, however, might be London-based Japanese artist Kentaro Yamada’s Neanderthal scent, a commercially available “conceptual perfume” contained in a giant hand ax–shaped bottle, sculpted by the contemporary caveman Will Lord (a self-titled “prehistoric survival expert”).

Just as Yi and Fillion’s Beyond Skin envisions imaginary futures, Neanderthal considers the unwritten past. Yamada, who developed two Neanderthal scents with perfumer Euan McCall, calls perfume “a strange cultural production that doesn’t have a shape, only an olfactory profile,” one that “takes on its own life” in the moment when scent meets air and skin.

Both Yi and Yamada’s projects are, essentially, conceptual provocations to think about the imperceptibility of air. In Yi’s words, air is “a medium, a charged site, where olfaction is activated” as molecules act upon us in an ecology of exchange. Yi’s Biography reminds us that to wear perfume is always to ornament ourselves with the unseen.