Shooting Star

Roger Deakins has received five Oscar nods, and now there’s talk of a sixth for No Country for Old Men, his ninth collaboration with the Coen brothers.

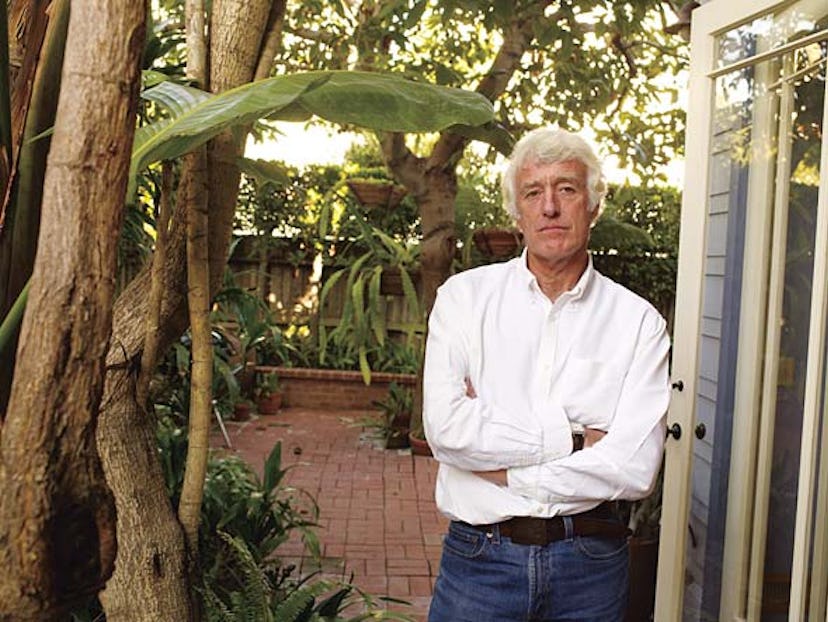

It’s a perfect Friday morning in Santa Monica, and the grapefruit trees hang heavy in a side-yard garden off Main Street: the very cliché of California beach-town quaint. Inside a shingled bungalow, morning papers from both coasts are laid on the kitchen counter, all of them open to rave reviews of Joel and Ethan Coen’s latest, No Country for Old Men—perhaps the most violent, suspenseful and grimly beautiful film of 2007—which will open later that day. What’s unusual about the reviews is that a crew member, director of photography Roger Deakins, is consistently singled out for his contributions to the film. (“His work is a marvel,” writes Pulitzer Prize laureate Joe Morgenstern in The Wall Street Journal.) Deakins himself would likely be uncomfortable with, if not outright embarrassed by, such talk. His clothes—a plain, masculine uniform of jeans, a white oxford shirt and boots—suggest practicality, thrift and an aesthetic preference for form over adornment.

As he now sits folded into a low chair in his cheery, Pottery Barn–perfect living room, Deakins seems cramped indoors, as if the open landscape of his youth would more comfortably suit his lanky frame.

At 58, Deakins has a handsome face that has worn well, like good cabinetry, and a shock of Clinton-esque silver hair long enough to suggest a youthful rebellious streak never entirely outgrown. His pleasant accent—after he somewhat reluctantly unlocks his jaw—bears traces of his rural upbringing in maritime Devon, England.

Deakins’s résumé includes: Jarhead, 2005; Fargo, 1996 (pictured here); No Country for Old Men, 2007; Barton Fink, 1991; ;Sid & Nancy, 1986; The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, 2007.

“When I get buzzed is when I’m looking through the camera and Tommy Lee Jones is doing those scenes,” Deakins says, noting one moment late in No Country when Jones and Barry Corbin sit in a shack and, excavating their burdened souls, seem to live as if the camera doesn’t exist. “It’s like I get a tingle going up my spine, even now. I can’t really get interested in just shooting something to make pretty photographs. I love the interaction of the camera with an actor who’s creating a character. That to me is the most special thing.”

No Country and the recent The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford show a master in full command of his mature style: It’s work that rises to the level of cinematic art without devolving into fey artiness. (The strong initial box office showing of No Country demonstrates that his cinematography can grip both a mainstream audience and the critics.) If he doesn’t exactly have a signature style, Deakins invariably creates a sense of place so immediate that it transforms landscape from an inert background into an active narrative force, almost like a character in its own right. Long horizons are his forte—before his recent work in the American West, he’d worked in Africa and Tibet—and Deakins’s wide-lens establishing shots have a formal rigor that evokes photographer Stephen Shore’s landmark color pictures of Seventies roadside America.

And yet, Deakins’s nimble camera also loves actors, or at least certain actors, like Jones and Brad Pitt, who meet his high expectations. Deakins began his career as a documentary filmmaker, and he continues to exercise the photojournalist’s habit of patient, alert observation with spellbinding results.

After more than two decades behind the camera, Deakins has his pick of work—up next is Stephen Daldry’s The Reader, starring Nicole Kidman—and his taste runs to the ambitious, nuanced material that Hollywood likes to shepherd toward Academy consideration. “I wouldn’t be very interested in doing a James Bond movie,” he says. “I like doing films that have something to say about people and situations.”

Deakins is, one might say, the cineaste’s cinematographer. He’s constantly in demand and—despite his reputation as a touchy perfectionist—widely admired in the industry. Early award-season commendations suggest that this might be Deakins’s year: He’s received five Oscar nominations, and there’s talk of a sixth for No Country. His résumé stretches back to the Eighties, when he made his name with the cult classic Sid & Nancy, about Sex Pistols singer Sid Vicious and his doomed junkie girlfriend, Nancy Spungen. In addition to the nine films he’s made with the Coens, he’s also worked with Martin Scorsese (Kundun), John Sayles (Passion Fish), Frank Darabont (The Shawshank Redemption), Ron Howard (A Beautiful Mind), Michael Apted (Thunderheart), Tim Robbins (Dead Man Walking) and M. Night Shyamalan (The Village).

“It’s an extraordinary list of movies,” says Sam Mendes, who first approached Deakins for American Beauty (scheduling conflicts meant the job went to Conrad Hall, who won the cinematography Oscar for it in 2000) before securing him for Jarhead and the upcoming Revolutionary Road, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet in their first post-Titanic reunion. “It’s one of the great absurdities that he hasn’t won an Academy Award.”

Deakins could hardly be less Hollywood: Mendes affectionately calls him “the least ingratiating person I know.” In fact, when not on a set, Deakins and his wife, James, often retreat to their house overlooking the English Channel, not far from his boyhood home in Torquay. “You can go down to the pub, and the people are talking about what the mackerel fishing season is like or the weather and the tides,” says Deakins. “There’s no thought of films. It’s just rural people. It’s a great counterbalance.”

As a boy, Deakins began watching movies at Torquay’s local “film society.” His father, a building contractor, raised Roger and his brother after their mother died young, and Deakins recalls that much of his childhood was spent ditching school to fish and ramble through the countryside. “Where I grew up was very much about landscape and big skies,” he recalls. “It had incredible, changeable weather.

I remember once in June it being, like, 70°, and half an hour later there was a snowstorm.”

According to Mendes, Deakins still has an eye for nature’s grandeur and an outdoorsman’s subtle understanding of how the skies shift—and what that means for the day’s shooting schedule. “He will say, ‘In 20 minutes the light will change,’ and it does on the stroke of 20 minutes,” says Mendes. “You can feel how much happier he is in nature. He’s a boat person, not a sofa person.”

Deakins took up landscape painting in his teens and got his first camera when he went to Bath Academy of Arts in the late Sixties. One of his student projects, inspired by the documentaries of Frederick Wiseman, was to record the culture of Devon’s isolated farming communities. He spent months filming the members of a traditional stag hunt, making a “record of their life,” he says. “Just little things, really. That’s what I was interested in.” His first professional job was a British television documentary about an around-the-world yacht race. Deakins played up his background in a fishing village and finagled a place for himself and his soundman among the crew for the months-long voyage. His first night out he regretted it.

“I’ve never been so sick in my life, before or since,” Deakins recalls, although he completed the journey, and the documentary. “The film was about the race and obviously about the visuals of storms and icebergs, but it was really about how people get on in such a small space, under such harsh circumstances, for such a long time.”

Life on a movie set wasn’t all that dissimilar, and Deakins proved to be equally tenacious in his new environment. His first fiction film was the 1983 British indie Another Time, Another Place, and he made other features before making 1986’s Sid & Nancy. That movie, which Deakins shot with a handheld camera in cramped sets that duplicated a room in the Chelsea Hotel, proved how useful his early training could be. Drawing on his agility as a documentary filmmaker, he threw away the tripod and with it the belief that cinematography required a huge crew. Although Deakins didn’t rely entirely on handheld techniques again until Jarhead, Sid & Nancy established his ability to create high-impact visuals while keeping a low-impact presence on set.

The average movie fan probably has only a vague sense of what a director of photography actually does—and Deakins himself admits it’s hard to know exactly where a director’s ideas end and his own begin. A DP is, in the most basic sense, the chief crew member, and his work may range from lighting the scene and composing the shot to managing the set in the director’s absence and making preproduction decisions about a film’s color palette. And while the DP may be well below the ranks of name talent that enjoy paparazzi coverage and back-end participation, a director’s artistic vision for a movie succeeds only if the DP is able to capture it on film.

While a dissatisfied DP can endlessly hold up a shoot, Deakins, says Jesse James director Andrew Dominik, “is no muss, no fuss.” Dominik, who had made only one prior feature, had definite ideas about the look of Jesse James based on his archival research and asked Deakins to evoke the woozy, unfocused appearance of 19th-century photographs. Deakins complied by custom-designing lenses that allowed him to focus on a central subject while the periphery blurred into a fog—and by framing a number of shots of Pitt and costar Casey Affleck through windows fitted with wavy antique glass. Dominik recalls that Deakins remained alert to the unexpected inspiration. He says that one shot late in the film—a ghostly reflection of Jesse James’s body in the lens of an old-fashioned box camera—exists because Deakins happened to realize its potential.

Deakins is best known for his work with the Coen brothers. One day Deakins’s agent called him to say that she had just received a weird script about a writer who goes to Hollywood. She couldn’t really explain it, she said, but the project was called Barton Fink and was to be directed by the Coens. Was he interested? Deakins pounced. He loved their films and agreed before she had a chance to elaborate. “My only nervousness,” he recalls, “was the idea of two brothers directing and how that worked.”

How it worked, then as now, is seamlessly, says Deakins, who has photographed every Coen brothers movie since then and admires the way the brothers seem to work with a single mind. The pair are famous for running a tight set, with a bare minimum of takes, and Deakins, a model of efficiency who shares their taciturnity, was apparently born for their crew. (A typical feature burns between 600,000 and a million feet of film. Deakins shot only 238,000 feet for No Country and a mere 175,000 for Fargo.)

“We don’t have deep conversations about any shot,” Deakins notes, explaining that after intensive preshoot prep, there is very little left to decide on set. “It’s more instinctive. I might say, ‘This feels right—what do you think?’ and Joel might say, ‘Okay, perhaps we could be wider,’ and Ethan might add, ‘What about a little move here?’”

The Coens challenged Deakins to explore more flamboyant visual territory—think of the gates-of-hell burning hotel corridors in Barton Fink—that he calls a “more involved camera style,” in contrast with the “observational” style of Fargo. “It’s ironic Roger’s ended up working in a high style,” says Mendes. “I challenge you to believe that a shy and soft-spoken Englishman was responsible for such an outrageous film as Barton Fink.”

Deakins has received Oscar nods for Fargo, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, The Man Who Wasn’t There, Kundun and The Shawshank Redemption. But the spare and lonely look of No Country likely lies closer to his own instincts. The film delivers uninterrupted visual pleasure, even as it creates enough suspense to make audiences twist with dread. At moments it is chillingly understated, such as when Javier Bardem’s murderous character is announced only by the shadow of two feet underneath a door.

Though a quiet craftsman, Deakins admits, “I’m not the easiest person to work with. I can get grumpy, and I’m very demanding.” Once, he was the “whipping boy” because, as he tells it—without naming names—an actress “thought she wasn’t being photographed to look young enough.” He ended up being fired from the movie.

Asked if Deakins likes working with actors, Dominik tries to dodge the question: “He likes the ones who are good,” he says, noting that he can be “tough” to work with. But his fuller answer may explain why: “When he’s got his eye to the lens, he wants the world to come alive.”

Fargo: Gramercy/Neal Peters Collection