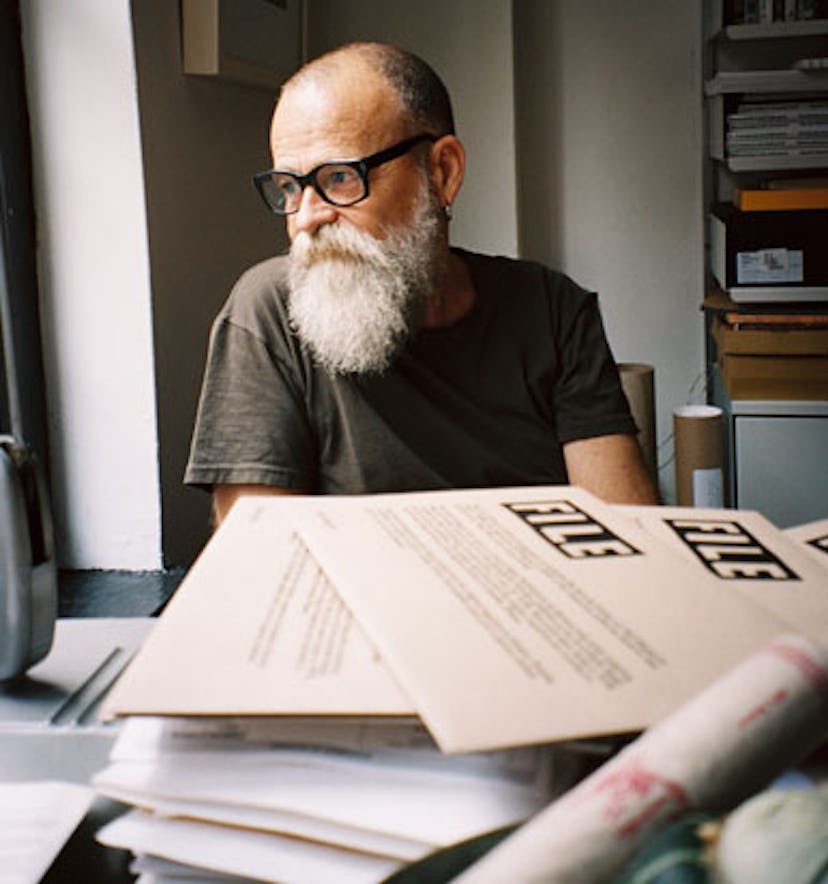

Behind The Seen: AA Bronson

Since the late 1960s, AA Bronson has been pushing the boundaries of contemporary art, first as part of the pioneering conceptual art collective General Idea, and then as a solo artist and head of...

Since the late 1960s, AA Bronson has been pushing the boundaries of contemporary art, first as part of the pioneering conceptual art collective General Idea, and then as a solo artist and head of the non-profit publishing organization Printed Matter. On the heels of a recent retrospective of General Idea’s work at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, Bronson opened a solo show at Esther Schipper in Berlin. Here, he discusses censorship and the role of government funding for the arts.

Last winter, after censoring a piece by David Wojnarowicz in the traveling Hide/Seek exhibition, the National Portrait Gallery refused to allow you to withdraw a piece of yours in protest. The entire incident was a reminder that the culture wars are ongoing. Could you see this happening in any other Western democracy? No. I can’t think of another place in the Western world where that could happen, and I don’t understand how this country came to have such a different sense of morality. One of the mythologies that’s present in political circles here is that culture is some kind of extra for fags and rich people, which is a peculiar notion because the culture industry is gigantic. It’s always dealt with here as if it’s something off on the sidelines—but if you think about how a city markets itself to the world, it’s only by being culturally sophisticated and culturally diverse that it will attract head offices of corporations. So it’s good business. If you start analyzing how the economy relates to culture, then Republicans should be supporting it.

There doesn’t seem to be much of a critical conversation in the art world about a larger purpose that art might play—a social, political, or spiritual role. I think there is an infrastructure of people involved with social or spiritual work, but they’re kind of invisible and they’re doing it with no money. There are a lot of extremely poor artists dealing with those kinds of ideas and they contribute a lot to society, but they’re not rewarded for that contribution.

What kind of work is rewarded? Collectibles for rich people. Luxury products. That part of the art world—the luxury product lines—are doing pretty well. And there’s room for that in the world, I’m not against it. But it’s pretty much what dominates at this point. In New York City, organizations like Creative Time and Performa do a lot for other kinds of art that couldn’t exist here otherwise.

What do you think would happen if the NEA were defunded? The truth is that the amount of funding here is already pitifully small. I suppose there would be some bankruptcies, but it seems to me that the visual arts is dominated by the marketplace here already. There’s so little support here for anything that lies outside the gallery system in the US. It’s already almost too late for the visual arts.

Your current show at Esther Schipper in Berlin, Invocation of the Queer Spirits, has plenty of gorgeous tangible works, but its essence is linked to the so-called ephemeral invocation. Can you speak about this piece? The invocation is probably the most complex work in the show. It’s about seeing ourselves as part of a community of the living and the dead. In North America, we’ve lost sight of community in general, let alone of the dead. For people of my generation who saw so many people die from AIDS, I think it’s of particular significance. We’re extremely aware of the community we lost but they’re still part of our essence and being. The piece is about that continuity.

Do you think that purely conceptual art could be celebrated again in American culture? It seems like it’s beginning to happen, like with Marina [Abramović]’s performance at MOMA. The invocation seems to arouse so much feeling. I think there’s a need for something deeper than a world of fabulous holidays.

More info at estherschipper.com and ago.net

Portrait: Ari Marcopoulos, 2010