Remember when the Guggenheim Museum was New York’s hottest club? From October 2018 to April 2019, it seemed like there was never not a line down East 88th Street—even after dark and in below-freezing temperatures—as museumgoers vied to see “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future,” the first major U.S. retrospective of the Swedish mystic’s work. When curators tallied the numbers, they discovered that more than 600,000 people had oohed and aahed in front of Klint’s swirling abstractions, smashing attendance records.

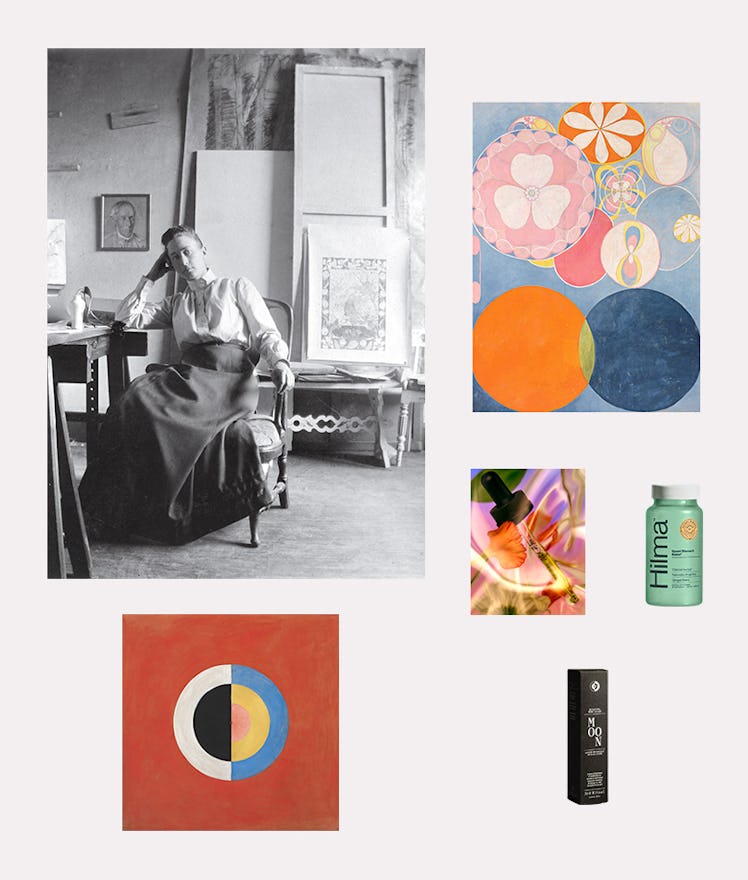

Three years prior, the Guggenheim’s Agnes Martin retrospective had attracted similar hordes, hypnotizing a new generation of museumgoers with the Abstract Expressionist’s ethereal grids and pastel stripes. And last March, the Whitney Museum of American Art unveiled “Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist,” following its successful run at the Phoenix Art Museum (where, with about 77,000 visitors, it was another attendance hit). At least a handful of the attendees at those shows were creative directors—in particular, those who work with start-ups in the women-led wellness space. A casual scroll through Instagram reveals Klint’s, Martin’s, and Pelton’s influences all over the direct-to-consumer industry: There are “Hilma” supplements, botanical moisturizers that bear a Klint-inspired logo, handwoven “Agnes” rugs in soft neutrals, silk-lined virgin wool coats inspired by one of Martin’s own, and nootropic beverages with labels that evoke Pelton’s otherworldly paintings.

Decades ago, Klint, Martin, and Pelton pioneered spiritually inflected abstractions and lived the kind of lifestyle that Big Wellness entrepreneurs and influencers aspire to. Klint channeled spirits with her mystic circle the Five; Martin studied Taoism and Zen Buddhism; and Pelton was a devout follower of Agni Yoga. Like Martin, Pelton left the New York art world and moved west, settling with a New Age community to paint electric visions of the desert sky and eventually becoming the first president of the Transcendental Painting Group. These three women used their art to overcome the chaos of their lives, and today, many of us are looking to their work in an attempt to overcome the chaos of ours. That’s perhaps why urbane marketers and young entrepreneurs are adapting these women’s aesthetics—and their witchy, otherworldly stories—to suit our consumerist impulses.

Clockwise from top left: Agnes Martin, seated next to one of her paintings; Martin’s Untitled #10 (1975) and Untitled #1 (2003); the “Agnes” coat by the lifestyle brand Permanent Collection; the “Agnes” rug from Field Guide; the astrology app Co-Star borrows Agnes Martin’s spare color palette and tidy geometry.

Martin: courtesy of Charles R. Rushton, © 2021 estate of Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Untitled #10, 1975, acrylic and graphite on canvas, 72 x 72 in: © 2021 estate of Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS); Untitled #1, 2003, acrylic and graphite on canvas, 60 x 60 in: © 2021 estate of Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS); “Agnes” coat: courtesy of Gareth Hacker for Permanent Collection; “Agnes” rug: courtesy of Field Guide Los Angeles; Co-Star app: courtesy of Co-Star Astrology.

“Agnes Martin was always well-known in the art world,” says Kyle Chayka, the author of The Longing for Less: Living With Minimalism. But for the design world, he says, a retrospective such as the Guggenheim’s is “almost like a new album dropping.” In other words, the work becomes top of mind, like a song stuck in your head whether you know it or not. Martin’s grids, Klint’s swirls, and Pelton’s gradients played well on the ’gram after they were photographed on museum walls, so why wouldn’t they make a lasting impression when applied to packaging that’s promoted in the same feed? “Most people experience art on a screen that’s about four inches tall, so what their eye is going to be attracted to is likely something that’s colorful and has a palette that’s calming yet exciting, and I think these artists have that,” says Lolita Cros, who curated the art inside the Wing’s coworking spaces. “When you scroll through Instagram and these palettes pop up, your eye just goes to it. You want to click on it. It’s like cotton candy.”

That magnetic appeal seems to extend beyond the visual and into the realm of name recognition. Perhaps the most obvious “tribute” to these artists is Hilma natural remedies, an herbal medicine brand. “The exhibition was at the Guggenheim at the time we were launching, and we had all seen it and been struck by it,” says Hilma’s cofounder and chief brand officer, Lily Galef. “Once the name came up, it just clicked. It was such an obvious fit [because it communicated] the magic and power of the natural world” that the supplement brand wanted to capture. “We joke that it sounds like the Swedish grandmother you want to take care of you in a moment of need, so it felt spot-on,” Galef adds.

Some brands utilize Klint’s, Martin’s, or Pelton’s earthy, esoteric aesthetics as a way to differentiate themselves from the Matisse cutout–inspired shapes, primary colors, and childlike pastels that have defined the past decade of graphic design (see: Glossier, terrazzo, Casper mattress ads). The logo of 3rd Ritual, a company that produces aromatherapeutic creams and a brass candleholder for meditation, evokes the Klint painting Group IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 17 (1915) while also horizontally flipping the yin-yang symbol that appeared on Korea’s earliest postage stamps. Aromatherapist and yoga instructor Jenn Tardif launched the brand with her design director husband, Pierre, in 2016, and set out “to challenge the status quo” design-wise. The mostly black and white look of Co-Star, the astrology app with 1.5 million Instagram followers, was deeply influenced by Martin, according to founder and CEO Banu Guler. “Martin’s idea of aesthetics as a way of making space for peace was a huge basis for the concept and design of Co-Star,” Guler says. “Everyone I know who loves these artists’ work is also deeply familiar with who they were—there’s an identification aspect to it. Our fundamental difference from other apps isn’t that it’s horoscopes, but that we’re trying to create zen rather than anxiety.” After seeing “Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist” in Phoenix in 2019, Kin Euphorics cofounder and CEO Jen Batchelor paid homage to Pelton while launching the nootropics beverage Dream Light in December 2019. Some of the “dreamscape” graphics for the “unboxing experience” are directly influenced by Pelton’s paintings.

Clockwise from left: Agnes Pelton in 1957; Pelton’s Orbits; Pelton’s work directly inspired the merchandising imagery for Dream Light, a nootropic beverage from Kin Euphorics.

Pelton: courtesy of Carolyn Tilton Cunningham Family Collection, courtesy of Nyna Dolby; Orbits: courtesy of the Collection of Oakland Museum of California, Gift of Concours d’Antiques, the Art Guild of the Oakland Museum of California; Kin Euphorics: courtesy of Center Design for Kin Euphorics.

Design aside, young creatives have embraced Klint, Martin, and Pelton because the artists were all forward--thinking outcasts. That can give even the most commercial products some street cred at a time when most things don’t feel original anymore. Though Klint was Sweden’s best botanical illustrator at the turn of the 20th century, “People thought she was nuts,” because she and her mystic circle channeled spirits, says Verena von Pfetten, a cofounder of the cannabis lifestyle brand Gossamer. “Now, a hundred years later, she’s being viewed through this entirely different perspective”—much like cannabis and other previously stigmatized substances, which are being embraced by Big Wellness. Since Gossamer avoids being “trippy” aesthetically, the Klint show suggested other ways to reference altered states.

In the age of self-care, Martin’s story is almost a parable: As her art world star rose, she suffered increasingly worse psychotic episodes. Eventually, she dumped her art supplies at a friend’s gallery, destroyed most of her paintings with a mat knife so no one could see or sell them, bought a camper, and ping-ponged between trailer parks before building an adobe cabin near Santa Fe. In New Mexico, she embraced a near-monastic lifestyle. “Agnes Martin’s mental health is highly visible in her art,” says Verena Michelitsch, Gossamer’s cocreative director. “These artists were working so many years ago, and only now is it okay to publicly discuss these things.”

Chayka believes Martin has become shorthand for the mythology of a lone woman painter in the desert. Along with Klint and Pelton, Martin “created these amazing aesthetics and had super-original, visionary ways of being in the world,” he says, pointing out that the lifestyle brand Permanent Collection sells a $1,200 wool “Agnes” coat named for Martin, based on the chore coat she wore in a Diane Arbus photo. “Brands are going to co-opt them and their work sooner or later.” Von Pfetten, for her part, believes that there is simply something in the air right now that is drawing us to their legacy. She points out that four months before the pandemic, Gossamer published an article in their magazine and on their site about Georgia O’Keeffe’s apocalypse bunker. Klint, Martin, Pelton, and other transcendental artists are seeing a resurgence because the world has become such an overwhelming, anxious place. “I don’t think our interest in them is a coincidence,” von Pfetten says. “The rise of people consuming cannabis and mushrooms, and microdosing and all of that, that’s also not a coincidence. These things are all connected.”

This article was originally published on