Vivienne Westwood Fall ’92 Channeled Marlene Dietrich at Her Chicest

Welcome to Forgotten Runway, a deep dive into some of the more niche presentations in fashion history—which still have an impact to this day. In this new series, writer Kristen Bateman interviews the designers and people who made these productions happen, revealing what made each one so special.

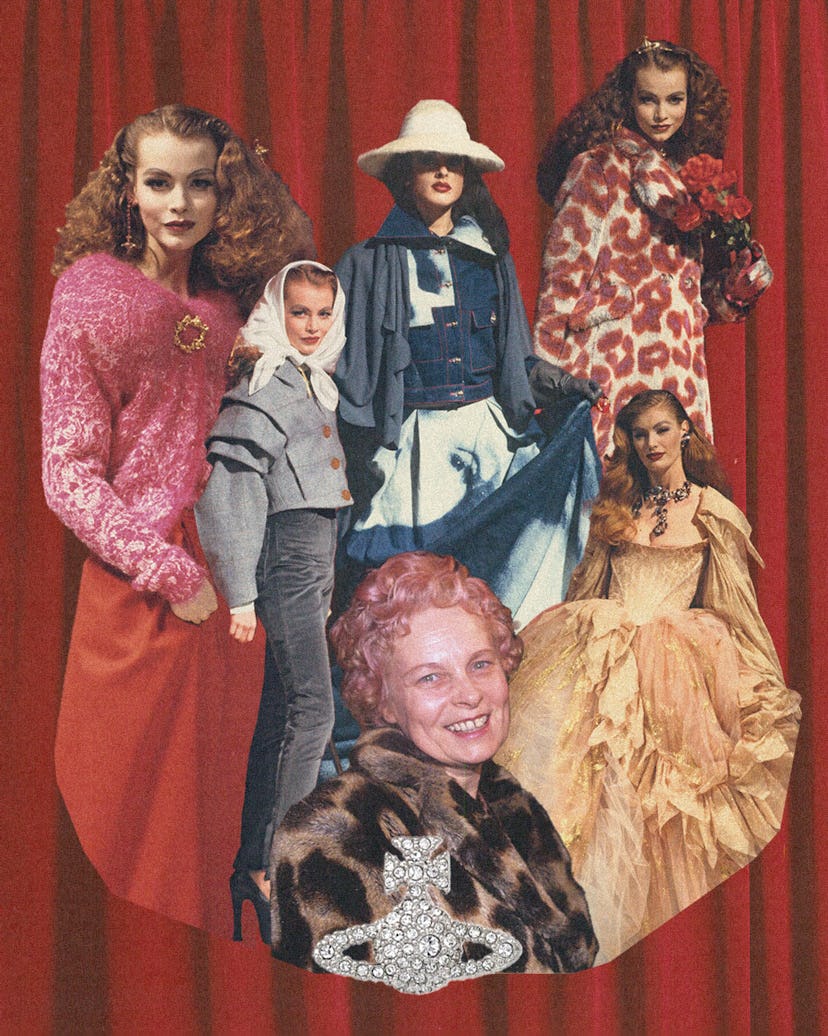

Vivienne Westwood’s fall 1992 runway was filled with fashion muses prancing down the runway, cosplaying as fully animated caricatures of old Hollywood stars. Inside a Paris museum hallway covered in red curtains, the show, titled “Always on Camera,” featured a female air pilot wearing a silver metallic cap and draped trousers, a silver screen starlet in the now-infamous Frans Hals lace-trimmed babyface corset, and mock daytime TV doyennes donning severely tailored suits in pink leopard print with matching, massive, heart-shaped bags. “The inspiration for the show was, clearly, Marlene Dietrich, and the Hollywood, silver-screen era,” Andreas Kronthaler, Vivienne Westwood’s creative partner and husband of decades who co-designed the collection, tells W. “She is one of the most outstanding movie actresses in terms of the image she created for herself—very much so with the help of her director in the beginning, Josef von Sternberg, who pushed her appearance to an extreme. I don’t think we have ever seen something like that since.”

“Always on Camera,” though not often talked about as much as some of Westwood’s other shows, left a major impact on fashion and Westwood’s body of work. This was the first time the brand showed outside of Azzedine Alaïa’s house and atelier in Paris’s Marais, establishing the label as a major player in the European fashion scene. The introduction of the pink leopard print would become a house code—later covering shoes, handbags, socks, and corsets. Carrie Bradshaw even carried a luggage trunk with the pattern in an episode of Sex and the City.

By the time “Always on Camera” took place in 1992, Vivienne Westwood had grown to be a powerful voice in the industry, especially as a female designer who constantly pushed the fashion conversation forward, bending boundaries that touched politics and socioeconomics. She created new silhouettes that her contemporaries like Jean Paul Gaultier would later reference. (Take, for example, the cone bra-like, underwear-as-outerwear seen in her spring 1982 “Buffalo/Nostalgia of Mud” collection, or the mini-crini skirt she presented between 1985 to 1987, designed as a new version of Victorian crinoline. This style challenged the longer, more demure puff skirts released by Yves Saint Laurent and Christian Lacroix at the time.) “Always on Camera” was a character study of fashion storytelling.

Today, it’s nearly impossible to scroll through social media without seeing a Vivienne Westwood piece worn by the biggest stars. The corsets and pearl necklaces have gained massive popularity for a new generation on TikTok, and there’s an explosion of archival Vivienne Westwood imagery appearing on Pinterest, Twitter, and Instagram—where mood board-inspired accounts like @thewestwoodarchives go viral every time they post.

Back in ’92, the designer’s presence was just as felt in the fashion industry. The way Westwood interpreted prints was unequivocally unique, as she often worked with fine art references. For “Always on Camera,” she took the abstract image of Dietrich and pushed it into new territory: putting an iconic photo of Dietrich posing in front of a car wearing a men’s suit and transposing it onto denim.

A look from Vivienne Westwood’s “Always on Camera” collection, 1992.

“There was a lot of denim in this collection where we etched Marlene Dietrich’s face onto the material and cut up garments—eyes on the bum pocket, lips on the crotch. We played with her image, made layers, cut up jean jackets and skirts,” says Kronthaler. Hand knitted pieces were printed with glitter lace and topped off with padding around the chest and shoulders for an extreme silhouette. Hairstylist Mark Lopez created vintage-inspired coifs that looked like they were from decades past.

Dietrich’s film Morocco was a major source of inspiration for Kronthaler, he tells me as he thinks back on it: “These very overdrawn eyebrows and this very particular beauty just hitting you, and she says the words in a soft German accent: ‘I don’t need any help,’” he recalls of Blond Venus, 1932, in which the actress is dressed up as a gorilla and performs a striptease. Then, The Devil Is a Woman, from 1935: “The costumes are the absolute end of what’s possible,” he adds. “They’re made by Travis Banton. It’s the greatest costume film ever made, and hasn’t only inspired me—it has inspired every fashion designer I know.”

A look from Vivienne Westwood’s “Always on Camera” collection, 1992.

Of course, Dietrich was known for her androgynous style and penchant for suits. “Another important part of the collection is suiting, which was made in very special estate tweed—we had it woven in Scotland—and we made these exaggerated men’s suits,” Kronthaler says. “Of course, the great thing about it all was the proportion, which was achieved through elevated platforms which lifted the girls up to an extreme height. They were 22 centimeters higher than they were supposed to be, wearing heels hidden under these elongated Marlene Dietrich trousers.”

A few of the pieces touched on Westwood’s punk foundation, too. “I remember there were some clothes made out of ‘display’ velvet—a floor-length trench coat with matching shocking pink hair,” Kronthaler adds, recalling Westwood’s earliest work, which incorporated rubber, safety pins, and other non-traditional materials. “Shocking pink is the color of this era, and we always made things out of the most unusual fabrics.”

A look from Vivienne Westwood’s “Always on Camera” collection, 1992.

As Dietrich was the big inspiration behind the show, the brand invited her to attend and sit front row; she unfortunately couldn’t make it. “We delivered an invitation to her at the Avenue Montaigne because of course, everybody who has the choice wants to spend the autumn of their life in Paris,” Kronthaler remembers. “But she was too ill then, and died a month or so later, in her nineties.”

True to most of Vivienne Westwood’s 1990s shows, the finale of “Always on Camera” saw a procession of big ball gowns waltzing down the runway. This time, they were made out of tulle, printed in trompe l’oeil glitter lace, resembling Dietrich herself in the 1947 film Golden Earrings, in which she played a glamorous, nomadic Gypsy. “The title of the collection ‘Always on Camera’ had a lot to do with the philosophy then,” Kronthaler says. “‘Always dress up, because one is always on camera’—and, in any case, one never knows what happens...You always want to look the best you can, because it is the first impression you make that will last forever.” Few designers explore fantasy the way Westwood does—and few cinematic icons held their own unique style in the way that Dietrich did.