The Tiffany Lock Collection Gives Functional Hardware a Glamorous Upgrade

The padlock, a symbol of both Victorian courtship rituals and punk insouciance, gets the fine jewelry treatment.

While Tiffany has long been linked to a glamorous sense of nostalgia—in particular, to a certain gamine immortalized in a book and movie bearing the company name in the title, and to its legendary late designers Jean Schlumberger and Elsa Peretti—its offerings have always been inventive and in step with the times. Among Tiffany’s advancements are the discovery and introduction to the jewelry world of gemstones including kunzite, tanzanite, tsavorite, and morganite (named after regular customer and collector J.P. Morgan), and the creation of ingenious hybrid designs that are sold as one piece and can be transformed in multiple ways.

Debuting globally in September, Tiffany Lock, a collection of four all-gender bracelets, re-envisions the padlock, an oft-riffed motif from the Tiffany archives, and transforms it into a gleaming symbol of inclusivity. The bracelets, available in 18-karat yellow, rose, and white gold, with or without diamonds, feature an innovative clasp that mimics the swiveling mechanism of a functional padlock. “No rules. All welcome” is the openhearted tagline of the advertising campaign, which stars Imaan Hammam, the Dutch model of Moroccan and Egyptian descent, and Tyshawn Jones, the American pro skateboarder.

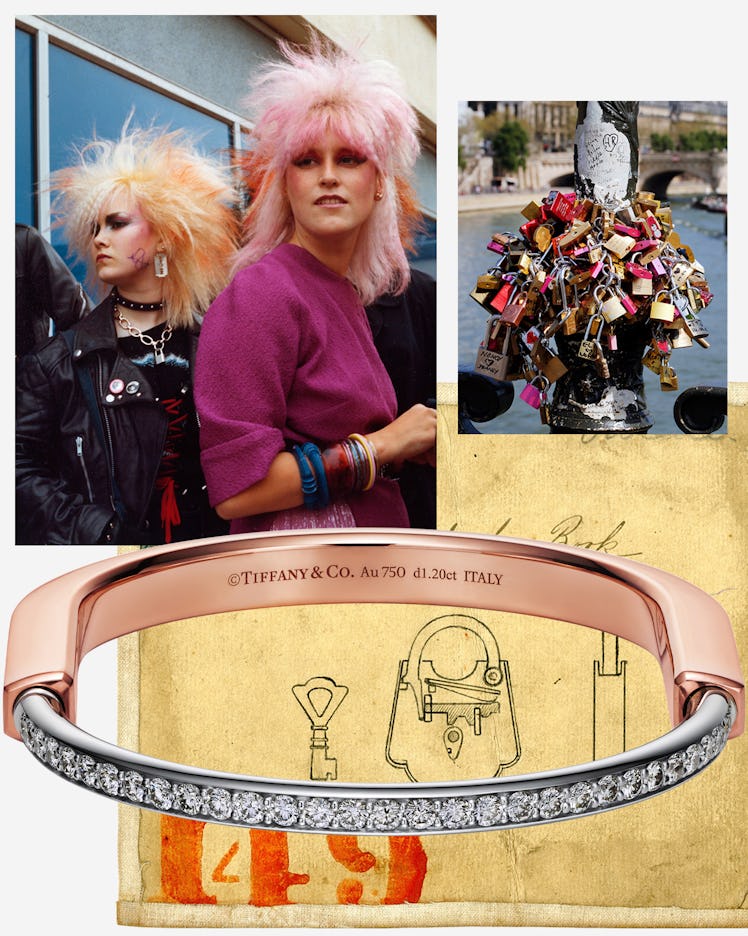

Two Colourful Punk Girls, 1983, photographed by Shirley Baker.

Love padlocks at the Pont des Arts in Paris, 2018.

Padlocks have been used in jewelry since the Regency era, when they appeared as charms on women’s necklaces, pendants, and bracelets, and on the extravagant collars, many of them engraved, of the dogs of aristocrats. “I am his highness’s dog at Kew; Pray tell me, sir, whose dog are you?” reads an epigram that the poet Alexander Pope had engraved on the lock of one of his pampered pooches. The trend took off again during the fin-de-siècle reign of Queen Victoria, when dainty padlocks were worn on the pendants of one’s intended; some versions came with a key and were gifted by gentlemen when they went away for extended periods of time. (Not all such historical trinkets were quite as romantic: Padlocks, of course, were an essential component of the cruel chastity belts used from the 15th through 18th centuries.) To this day, there are bridges in Europe where lovers affix padlocks with their initials onto the railings and throw the keys into the water below as a symbol of their love.

A Tiffany Lock bangle in 18-karat rose and white gold with diamonds.

“Padlock for Book,” a blueprint from the Tiffany archives.

In high fashion, padlocks have been incorporated into the collections of many leading designers, from Elsa Schiaparelli and Franco Moschino to Alexander McQueen and Schiaparelli’s current successor, the media darling Daniel Roseberry. Away from the exalted runways, despite or because of their association with restraint, they have been a go-to for stylish provocateurs since the punks of the late 1970s and ’80s wore them on bike chains and dog collars.

Comtesse Marie-Thécle de Nieuwerkerke, née Mademoiselle de Monttessuy, 1840, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter.

But the roots of Tiffany’s lock designs—including a limited-edition version by artist Daniel Arsham, available next year—are closer to home. Since its inception, in 1837, the company has sold padlocks as part of its objects and homeware collection. Starting in the 1950s, Tiffany brought the functional hardware into the world of personal adornment, as key rings, brooches, and necklaces. Even the gender-inclusive approach to marketing is in the company DNA. In a ’50s advertisement for “useful and distinctive” gifts, the accompanying copy takes great pains to point out that these items, including an elegant 14-karat-gold padlock money clip, are “thoroughly suited to masculine taste.” If that instinct proves right, the all-embracing appeal of its new Lock will succeed in widening Tiffany’s circle of loyalists.

© Courtesy of Estate of Shirley Baker/Mary Evans Picture Library; Chesnot/Getty; Courtesy of Tiffany: Tiffany Archives; Courtesy of Landemuseum, Germany.

This article was originally published on