Eyricka Lanvin, the mother of The House Lanvin on HBO Max’s show Legendary, can still recall how liberated she felt during her first walking competition in 2001. “I wore a wig, Nine West stilettos, and this body-hugging snakeskin dress,” she tells W. “I looked in the mirror and said, ‘I can’t, I will not go back to my past self.” Growing up in “deep” Brooklyn, Lanvin struggled against the confines of gender binaries in clothing. That is, until she finally stepped foot on the ballroom scene. “As a person who was figuring themselves out, it was tough. Guys wore guy clothing. Women wore women’s.” Now, as one of ballroom’s reigning queens, Eyricka Lanvin’s fashion choices are a direct reflection of how she’s feeling. “I am a comfortable, street-style girl. If I wake up and want to wear jeans and a baseball cap, I’ll do that. If I want to wear a pink jumpsuit and hoops, I’ll do that, too. What is gender? Follow your heart and wear what feels right.”

In the past five or so years, the term “genderless” has become the hottest buzzword in the fashion industry. Brands worldwide have applauded and embraced the shift, noting their customers’ shopping habits and, in turn, putting out collections and capsules that celebrate gender fluidity or aren’t relegated to the men’s/women’s section. But while this, frankly, elementary release from the binaries of womenswear and menswear spreads throughout fashion, I wonder: Where was the applause for queer and trans people who have been stepping outside of the fashion gender binary for centuries?

The House Lanvin as seen in Season 1 of HBO Max’s show Legendary.

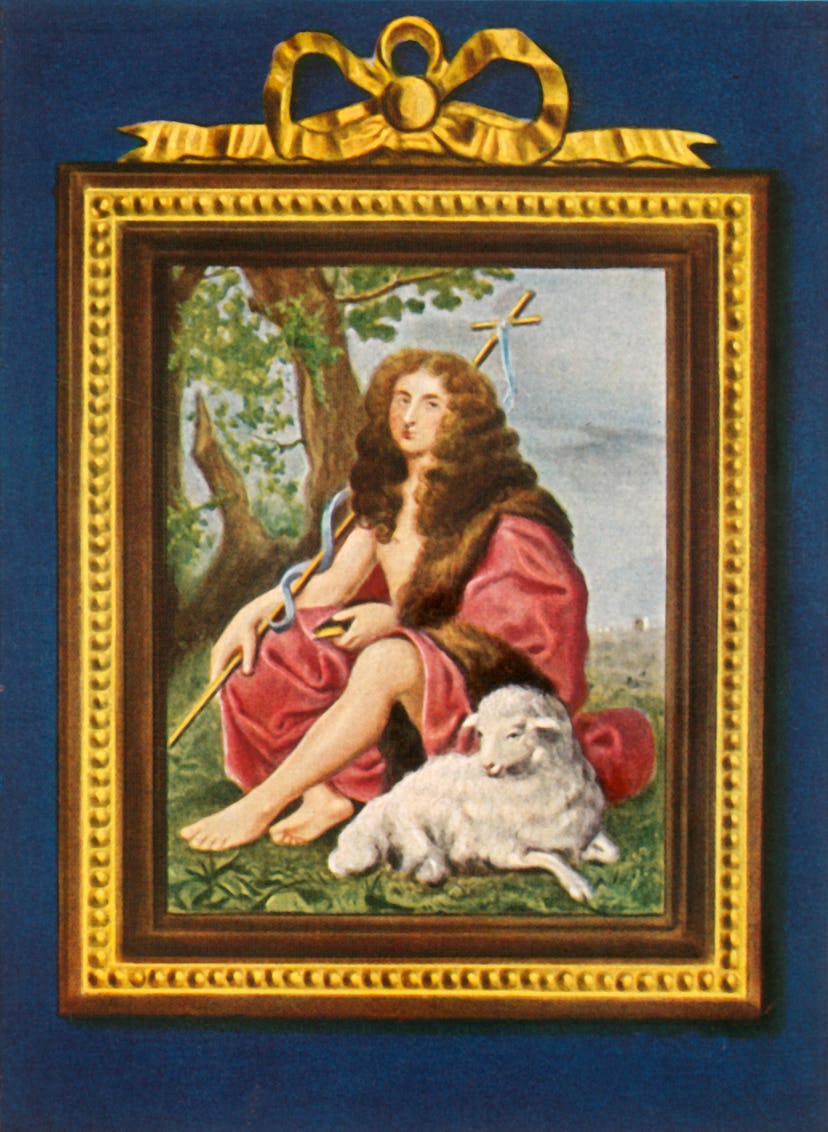

Take Philip I, Duke of Orléans, who famously rejected fashion binaries during his reign over France in the 17th century. While he’s certainly not the first person to wear clothes assigned to his gender identity, the queer royal wasn’t shy to express his feminine side in the royal courts. According to the biographer Christine Pevitt, the Duke was always “perfumed, bejeweled, and extravagantly clothed in lace and silk.” Like the Duke, wearing feminine clothing as a gay cis-man was never something that I shied away from. My closet is lined with women’s blouses and coats, and the distinction of what section they are usually found in at the store never mattered. To me, an uptick of “genderless” fashion brands is only a marketing tool that ultimately reduces the way LGBTQ+ people have expressed themselves for centuries to a mere trend.

I’d like to clarify that I’m no spokesperson for the LGBTQ+ community at large, nor do I intend to be. I am merely one of the many who find joy in wearing clothes and observing how clothes continue to change. And I don’t mean to naysay or gatekeep—I’d merely like to pay credit where credit is due.

Trans model Moon Mendoza has denounced the constrictions of gendered clothing since she was a child; The 5’ 8” Filipino-American appeared in downtown New York City donning skirts and dresses even before her transition. Each stride in her walk was like an echoing indication of someone who lived fully as themselves in clothing that pushed against society’s norms. Like Lanvin, she, too, believes gendered clothing is a thing of the past thanks to LGBTQ+ people. “Whether it’s menswear or womenswear, masculine or feminine, they’re all just labels,” she says with a tone in her voice that indicates she’s completely over it. “We should definitely celebrate straight people crossing the line. But, more importantly, celebrate clothing with no boundaries.”

One designer whose ethos has always aligned with breaking fashion’s gender binaries is Central Saint Martins graduate Patrick McDowell. Take his latest collection, “Catholic Fantasy” (which features a sheer crystal papal robe and long stockings galore). Debuting online earlier this spring, there is no distinction between menswear and womenswear in the line. But society’s gender norms still weigh heavily on the designer. “I’m still very conscious of how I dress being linked to how society sees the male figure,” he says. “I know I look fantastic in a mini skirt, but I don’t wear them often. I would, however, wear mini shorts without thinking twice despite the only difference being one extra seam. It’s preposterous when you think about it like that.”

However, McDowell does maintain that pushing back on gender binaries in fashion can lead to a sense of liberation. According to the designer, crossing boundaries allows him to create his own path in life. “If I wasn’t queer, I’d be locked inside all of those terribly sad boxes that heteronormative people are lumbered, which would be such a dull way to live.”

Drag ball in 1988 in New York City.

Vanity Legend at the Drag Ball in 1988 in New York City.

This liberation is exactly what happened to Lanvin when she joined the Ball scene. In fact, Ball culture has always been a space where gender binaries in fashion cease to exist. Through all the shimmering glitter, tall wigs, and high stilettos, Ball culture was (and continues to be) a safe space for the LGBTQ+ community to express themselves in ways that the outside world couldn’t handle, especially during the 1980s when Ball’s roots were first planted. While the city slept, Black and Latinx members of the LGBTQ+ donned their finest, most flamboyant, clothes that were typically associated with the opposite of their gender. Once primed and pressed, attendees competed in several drag competitions and performances that alluded to a particular gender and social class. Not only did balls serve as a chance to get street cred, they also offered escapism—a chance for attendees to be themselves, choose their families, and live fully as themselves.

Whether it’s dukedom, underground societies, or designing, the LGBTQ+ community has always and continues to break down gender binaries in the fashion industry—not for marketing, but for survival. Kudos to “genderless” fashion for moving into the mainstream. But always remember: wear whatever feels right, and whatever the hell you want.

This article was originally published on