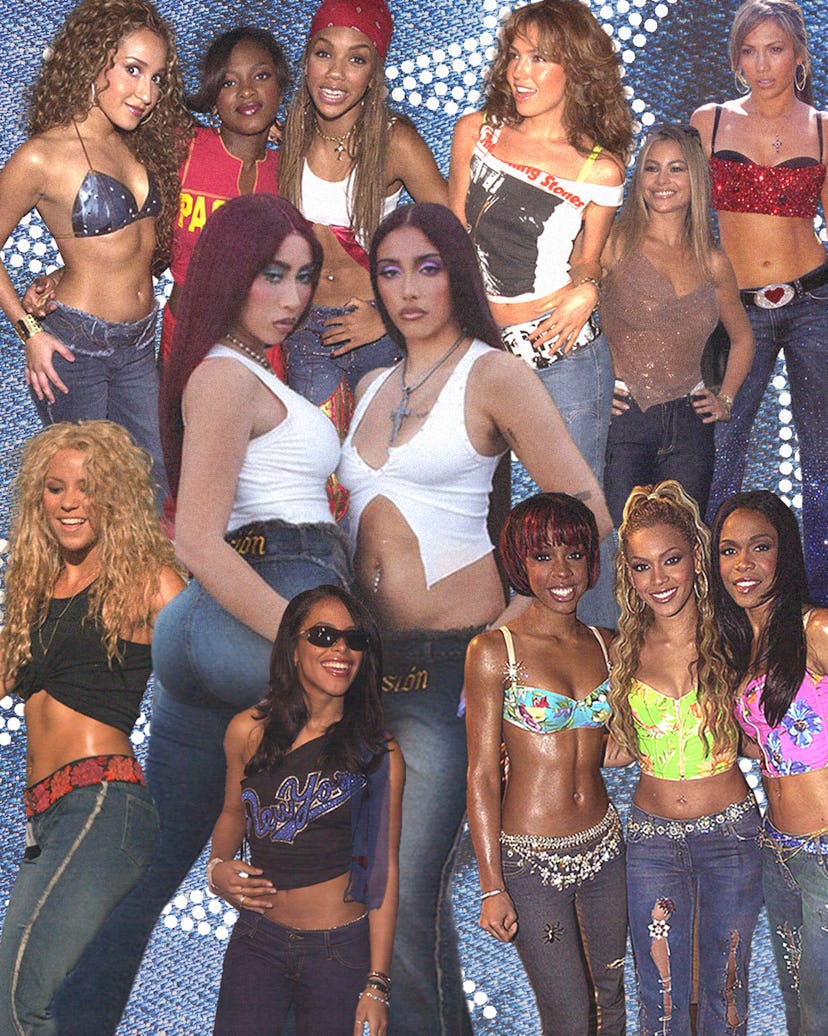

The resurgence of ’90s and 2000s fashion has become an undeniable and pervasive trend, thanks in part to Gen Zers who have made it their job to bring back archived pieces like micro-mini skirts, heavy lip liner, and zig-zag hairstyles. Now, add musician Kali Uchis to the list of those reviving looks of yore: she launched her denim brand Bodied by Uchis’ Obsesión line this summer, and the bedazzled, curve-hugging jeans beloved by R&B girl groups like Destiny’s Child and 3LW are poised to make their comeback, too.

Those who lived through the early aughts might remember the jeans that marked this era: low-rise, bootcut, sometimes frayed, with intricate stitching, rhinestones, and embroidery. Mariah Carey wore denim of this sort in her “Heartbreaker” music video, they were Shakira’s chosen mainstay, and Christina Aguilera couldn’t get enough of them, either. Out of this Y2K fashion staple came a trend particular to South America, which originated in Colombia: the uncompromising “Colombian Blue Jean,” a style that eventually changed the entire denim industry in Latin America—and the world.

The original Colombian Blue Jean had very specific defining features: they were always boot-cut and low-rise; most did not come with pockets, and were made from a stretchy, spandex-like fabric (think jeggings), with unique embroidery, appliqués, and, in some cases, bright rhinestones. Most importantly, this style of denim was made with butt-lifting technology called “levanta cola,” which creates the appearance of a bigger cola (an endearing term for “butt” in Spanish) via its stretchy material and strategically placed embroidery, which outlines all the right places. A quick search on TikTok of the #LevantaColaJeans or #ColombianJeans hashtags reveal rows of mostly Latina women flaunting their enhanced colas and cinched waists. On Google, you’ll find a directory of small-owned businesses across New York, Miami, and Southern California selling the specially designed denim—you can even buy a pair from vendors on WhatsApp.

The exact date levanta cola jeans entered the market is unclear, but its rise in popularity goes back to the ’90s and early aughts, just after the advent of cable TV entered Colombian families’ homes. This was a time when hip-hop culture had gained global popularity; images of early iterations of the levanta cola blue jean are reminiscent of Black and Brown women’s fashion aesthetics from the 2000s. The impact of Black and Brown artists on trends and styles of that time spans generations and has had no borders. The jeans ultimately became a staple in Colombian culture that (literally) shaped denim wear—and it’s a culture that is very much still alive and thriving to this day.

While in the States, such styles of Y2K denim were critiqued as “tacky” and “cheap,” its predecessor in Colombia owned the attention. And it was the Colombian blue jean that inspired Colombian-American vocalist Kali Uchis’s new denim line, which features a fierce campaign with Lourdes Leon, in which the duo wears tight denim jeans, white tanks, heavy eye makeup, and thick lip gloss, recalling the aughts while simultaneously channeling trends of today. Uchis says the line is a nod to that bygone era, and is symbolic of “that person everyone sees down the street because they stand out. These jeans are for the people who are proud of who they are.”

She sees Obsesión as a celebration of the body and her own love for denim, which Uchis adds stems from her Colombian roots. Although she tells me she’s been excited to see people of all different shapes, sizes, and genders loving the jeans, she can’t help but notice others who have left degrading comments about the jeans looking “cheap” or like a “pulga” (“flea” in Spanish) on the brand’s Instagram account—many of whom she believes are Latinx themselves. “It’s an internalized self-hate of remembering when we would wear these when we were younger and having this stigma in our culture and heritage,” Uchis says. “The fashion industry is very classist. People who use the word ‘cheap’ are weird to me. These are good materials, what makes them cheap? Because it’s a Latina [wearing them]? Because it’s Colombian? It’s funny, the wording used around Latin styles…this is a beautiful thing for the Colombian economy.”

Uchis’s assessment is not far off. Colombia is the largest exporter of blue jeans in South America. In 2021, the exportation of Colombian blue jeans reached $14.7 million, with main consumers in the U.S., Ecuador, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Canada, Peru, Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Germany. Every year, about 50 million pairs of levanta cola blue jeans are fabricated in the country; their production has created an entire economy for Colombia that goes beyond coffee, gold, and the outdated (and extremely stereotypical) commodity associated with the country: cocaine.

Jillian Hernandez, author of Aesthetics of Excess: The Art and Politics of Black and Latina Embodiment and professor of gender, sexualities, and women’s studies research at the University of Florida, recently bought a pair of Obsesión jeans. She says the purchase makes her feel like she’s reclaiming a part of herself that struggled with racist ideas about “what aesthetics were good, which aesthetics were fashion, and which aesthetics weren’t,” she tells me. She recalls growing up “devouring” magazines like Vogue and seeing specific images in fashion that were deemed “acceptable” (most of which didn’t include the Levanta Cola blue jean, interestingly enough,) and remembers thinking, “Why would I want to associate with these racialized, working-class aesthetics when everything in the culture is telling me that what matters is what is in magazines?” Owning a pair of Colombian jeans in 2022 not only becomes a way of taking that power back, but Hernandez states it’s also a way of supporting the shift that someone like Kali Uchis can make right now. “She has this mainstream attention and people, women of color like her, are being recognized by fashion," Hernandez adds. “It feels like our aesthetics are finally being appreciated.”

I also struggled as the child of a first-generation, working-class Colombian family who wanted to feel empowered by her culture, but didn’t know what that looked like in a predominantly white, upper-class city like Cambridge, Massachusetts, my hometown. I often felt ashamed by my mom’s aesthetics—the dark, lined lips; the gold hoops; and the tight, bedazzled denim. The truth is, I had also internalized beauty standards of a country that historically did not include or represent women who look like me. Back in Colombia, it was empowering to see women owning their style—walking in their levanta cola jeans to work, to hang out with friends, to go out—they seemed so confident embracing a style that, back in the U.S., came with very specific instructions for who and where they could be worn without judgment.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized these beauty standards are rooted in racist, sexist, and classist beliefs. I’ve learned that wearing these butt-lifting, tight-fitting, curve-hugging jeans won’t mean you’re “tacky”—in fact, having your own personal style is something to be proud of, even more so if it connects to your community and your heritage. For all the girls who loved this style of jeans back in the day and are considering revisiting the look, it might be time to purchase a new pair—or rustle them up from the depths of your closet.