The Future of Fashion Is in the Past

For many style hounds, vintage and archival pieces make up the core of their wardrobe. Now, the fashion industry is beginning to catch up.

A couple of years ago, if you wanted to find a pristine piece from Prada’s spring 1996 collection, a Tom Ford–era Gucci bag, or that one pair of Dries Van Noten silk trousers that have been haunting you for years, you would have had to rely on grit, patience, and exceptional luck. Scouring eBay and spending hours flicking through racks at consignment shops has long been a sport for the fashion-obsessed, but for many people, sourcing vintage and secondhand designer clothes seemed like a time- and money-consuming gamble with unfavorable odds.

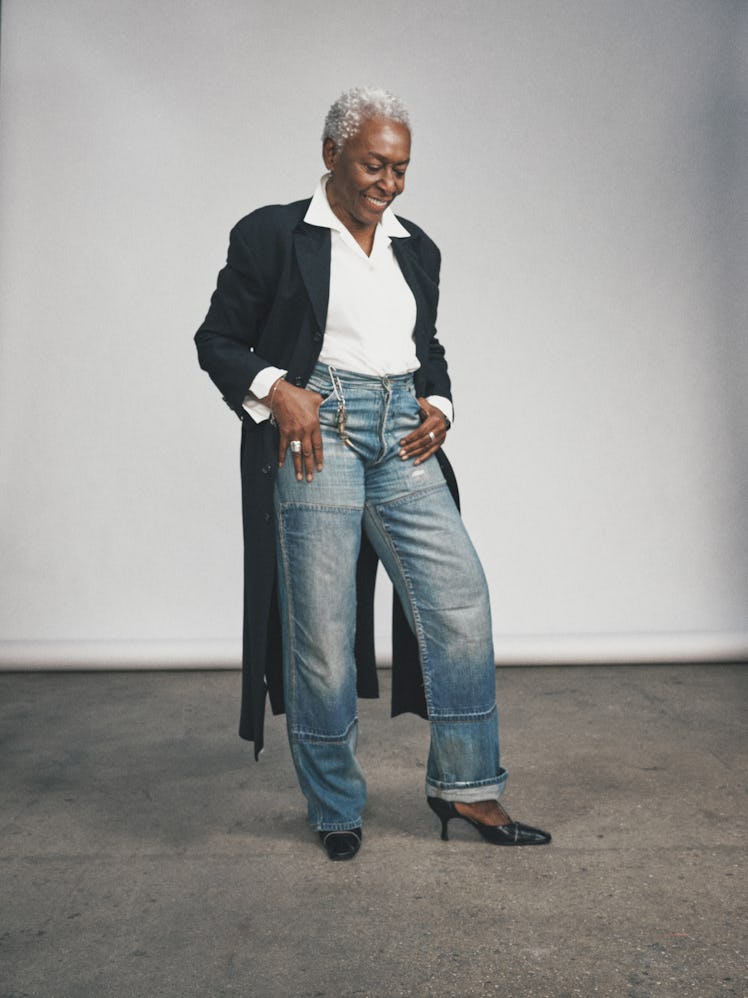

Bethann Hardison

“I recently allowed someone to come into my life who’s an organizer, and she made me get rid of things I never should have gotten rid of,” said Bethann Hardison, the model turned diversity advocate who has amassed four closets worth of clothing over the decades. “She just made me feel so fucking guilty!” Certain things, Hardison said, should be let go; others she keeps around as works of art, like the Hervé Léger shoes she wore to Iman and David Bowie’s wedding (“I keep them in the bookcase”), and a Willi Smith shirt. “You give things away along the way because you weren’t thinking of their value. You were just sharing. That’s part of the universe—recycling. But there are some things you just need to keep.”

Now—although there’s still plenty of luck involved—the thrill of the hunt can be distilled down to a few clicks. Not just due to the fact that the Internet has become home to myriad, easily searchable resale sites, but also because many of the designer brands themselves have finally begun to embrace the concept of a circular economy. The “re-commerce” ecosystem, which used to be considered a threat to a luxury house’s identity and a potential drain on its full-price customer base, now has an aura of environmental and social responsibility that eclipses the specter of the dreaded discount.

This sea change is as much about economics as it is about honoring the craftsmanship behind beautifully made garments, which can and should last a lifetime, or more. The women featured in this story have always understood that, whether they regularly wear pieces they’ve held on to for decades or have a vintage-shopping obsession. “Most things will always be in style because you have style,” said Bethann Hardison, a former model and advocate for diversity in the fashion industry. “It’s all about your attitude.”

Perhaps the clearest example of this shift is that when Dries Van Noten built his Los Angeles flagship last fall, he devoted two of its rooms to archival pieces, which customers can seamlessly shop alongside new-season merchandise. There’s also Gucci’s partnership with the RealReal, the latest in a series of designer collaborations with the fast-growing luxury resale site. It’s happening at the department store level, too: A year ago, Nordstrom devoted a special wing of its New York store to See You Tomorrow, a resale pop-up; this past fall, Selfridges in London launched “Resellfridges,” billed as “a way of opening the door to people who maybe wouldn’t have found themselves shopping pre-loved otherwise”; and at Fivestory on Madison Avenue, you’ll find vintage Chanel one flight up from Staud. In November, the global boutique aggregator Farfetch introduced Farfetch Second Life, which allows customers to earn site credit by trading in their used Dior book totes and Louis Vuitton Trevi PM bags. The wholehearted embrace of not-new clothing has even crept into Hollywood costume departments. In the latest season of The Crown, many of Princess Diana’s outfits are actually from the decades depicted. And instead of commissioning custom gowns for Tessa Thompson’s character in Sylvie’s Love, the team behind the film raided the Chanel archives for her onscreen looks.

It’s a boom time for those of us who might not be able to afford most designer goods at retail but don’t want to resort to fast fashion, whether it’s for environmental reasons (an estimated 17 million tons of textiles hit landfills in 2018 alone) or because of a refusal to compromise in terms of craftsmanship. We can search “zebra-striped Belgian shoes” on Poshmark and see what turns up, trawl for Prada coats in sizes S and XS on Vestiaire Collective, browse a curated selection of Phoebe Philo’s oeuvre on Re-SEE, or hope to be the first person to comment with our shipping zip code (a common way of reserving merchandise) on an Instagram vintage dealer’s photo of an Hermès belt.

Giving new life to unworn clothes is a breeze too. “Resale will be an assumed part of the luxury buying experience,” said Allison Sommer, the senior director of strategic initiatives at the RealReal. “Just like when you buy a car, you drive it off the lot and you know you can resell it. The same thing will be true for luxury clothing. It already is true; we’re just making it easier for customers to do that.” Gucci’s accessories seem to hold up particularly well after being driven off the lot, with an average resale value of 70 percent of the original price, according to data from the RealReal.

Sally Singer

“I’ve always worn pieces that have been worn by other people,” said Sally Singer, Amazon’s head of fashion direction, who first got into vintage shopping in high school, when she would put together eccentric thrifted outfits to go to nightclubs. “I’m really drawn to things that were made with love and intention, and were worn with love and intention over the years.” The backbone of Singer’s closet is vernacular vintage—from Goodwill, a vintage dealer in Milan, and the Santa Monica resale boutique the Colleagues. “Signed, meaningful, fashiony vintage” is another layer. “I used to say that I love to wear fired designers,” she said. “Probably because the thing that drives me to wear clothes are the things that make them less commercial and therefore unsuccessful with their corporate leaders.”

(The new effortlessness of getting rid of things does have a potential downside: When I asked Hardison if she had managed to hold on to the Stephen Burrows dress she wore at the legendary Battle of Versailles Fashion Show in 1973, she wasn’t sure. “I think he gave it to me,” she said. “But when you’re young, you know, the lighter the load, the freer the journey. You pass things on because you don’t realize what you have at that moment.”)

On the brand side, the shift toward incorporating resale into business models has been building slowly, but it accelerated during the pandemic. Gucci’s decision to link up with the RealReal came just a few months after Alessandro Michele’s announcement of the brand’s commitment to reduce its annual output from five collections to two, citing ecological concerns as well as creative ones. Just as many of us have been hit with an overwhelming urge to clear out our closets after spending months inside with all of our things, the fashion industry has had to come to terms with the sheer amount of stuff it’s been producing and accumulating.

Olympia Le-Tan

“My mum used to buy us vintage clothes when we were kids—old dresses, or things she’d find at the flea market or at jumble sales in Paris,” says Olympia Le-Tan, the designer who is known for her delicate embroidery work. Later in life she caught the bug, when she began working under Gilles Dufour at Balmain. “He would send me on research trips to the flea market, and I really enjoyed it. So every weekend I would go look for inspiring pieces and mainly buy them for myself.” The pink Chanel purse she carries here was originally her mother’s. “I was 15 or 16 when she got it, and I had my eyes on it forever,” Le-Tan said. “And finally, she accepted to trade with me for one of my own bags.”

“I can see the difference in tenor from conversations that I had with brands in 2016 versus conversations in 2020,” Sommer said. “About half of our consignors cite environmental reasons as one of the motivations to consign with us. And we see the same thing on the purchasing side, even higher for the millennial and Gen Z sets. They’re looking to brands to reflect the same changing values that they have.” Coupled with that pressure is the fact that resale, rather than cannibalizing a brand’s customer base, as many used to believe it might, actually complements it in a few different ways. Knowing that you would be able to resell a $5,900 bag for a similar price before you even get to the register reduces the barrier for entry, theoretically bringing in more customers. And for budget-conscious shoppers, particularly millennials and Gen Zers, a pair of secondhand loafers can serve as a gateway drug of sorts.

Olivia Kim, the Nordstrom vice president who masterminded See You Tomorrow, says that although the pop-up was temporary, she hopes it will lead to a permanent incorporation of resale into Nordstrom’s future offerings. “We know that for young customers, re-commerce is often their first foray into a new brand,” she said. “They may not be able to afford a new of-the-season handbag, but they can afford one from last season at a discounted price. That fuels brand affinity.” In other words: Why would you ever go back to Zara when you know what hand-tooled leather feels like? According to a 2019 report from the Boston Consulting Group and Altagamma, the resale market is expected to reach $36 billion in revenue this year (up from $25 billion in 2018) and is growing four times as quickly as the primary market. “With prices being so expensive, [the resale customer] may never ever be your customer,” noted brand consultant Bonnie Morrison. “But you can keep them from being a customer somewhere else.”

Behind the scenes, vintage clothes have always been an important element of the design process. Design teams often source archival pieces (from their own brands and from others they admire) to use as references—to, say, create a particular ruffle or approximate the cut of a sleeve. Now even those precious resources are being shared with customers of the Row: Designer Mary-Kate Olsen’s curated collection of decades-old pieces by Comme des Garçons and Issey Miyake is now available (price upon request) on the brand’s website.

Emily Gruca

Emily Gruca, a designer for Supreme, worked at the New York City resale shop Beacon’s Closet just after graduating from college. “I didn’t make any money there; I just broke even the entire time,” she said, laughing. “I can remember every piece that I sold back, and I’m like, God, I wish I hadn’t done that.” She estimates that about 70 percent of her everyday wardrobe consists of vintage and archival pieces, from the serrated Jean Paul Gaultier leather tops she finds on eBay and Poshmark to a cherished pair of the same Dolce & Gabbana jeans that Beyoncé once wore to the VMAs. “I mainly buy online so I can haggle with people,” she said. “And I also love when they post something wrong, and it’s listed as ‘Margiela Wacky Skirt’ but it’s a top, or with Helmut Lang pieces—they think it’s ripped, but it’s not.”

Emily Gruca, a designer for the streetwear brand Supreme, scours thrift shops all over Europe and Japan to inform her work—and (if there’s time) to add to her own impressive collection. Supreme has a unique relationship with the resale market; its tightly limited editions often get immediately flipped for upwards of 10 times the original cost. The brand’s devoted fan base can even affect the secondhand market for other companies: When Supreme announced its collaboration with Jean Paul Gaultier, Gruca noticed the prices for the couture designer’s archival pieces went up on eBay. “Everybody wanted to learn more about Gaultier—even 16-year-old skaters who had never heard of him,” she said.

Some brands have decided they’re not quite ready to get in on the resale action but are looking to upcycling or reissuing instead. Miu Miu, for example, recently released a line of 80 dresses made using reworked vintage pieces from as far back as the 1930s. Acne Studios has started reimagining its own archival pieces, applying leather panels or extra zips to jazz up unsold merchandise. On the flip side, the designer Olympia Le-Tan just began working with one of her favorite New York stores, Marlene Wetherell Vintage Fashion, to enliven garments that had been damaged, or were languishing in the shop, with beading, embroidery, or creative alterations.

“I think the brands that have embraced their archives and encourage mixing new stuff with older pieces have a healthier relationship to their customers and to their business and their legacy overall,” said Sally Singer, the former Vogue creative director who is now the head of fashion direction at Amazon. “Anyone who cynically thinks the future is only in front of us and doesn’t have anything to do with what’s come before is a bit out of date.”

How will these changes affect the way the fashion industry functions as a whole? For one, brands might use the data they collect from secondary sales to inform what and how much new product they make going forward. Additionally, Morrison wondered whether we might be headed into a designerless fashion industry that favors brand identity over individual creative vision. “People know what Chanel stands for, and it always stands for the same thing. Hermès is another label that is tuned so specifically to one vision, and the taste for that particular vision remains evergreen,” she said. “So will brands be thinking about that as they consider their own longevity and how they incorporate archival or historical pieces into that?”

Bonnie Morrison

Brand consultant Bonnie Morrison’s love of collecting vintage grew with the advent of the Internet. “I used to really have an eBay problem— I would get packages all day long,” she said. “My mailbox is clogged every morning with all of my saved searches, which have been going on for, like, 10 years.” She always keeps an eye out for Calvin Klein, David Cameron, and Rick Owens, “because it’s a way of reconstructing my first view of fashion, and what fashion looked like.” Now she’s started to think about passing along some of the pieces from her own collection. “I think back about how I used to consume clothes,” she said. “A lot of it was for fantasy occasions. But now, at 45, I realize I don’t need a Kentucky Derby hat.”

Her own 1970s Hanae Mori dress (found on eBay); Céline shoes from the Phoebe Philo era; personal bracelet.

There are some issues with the current state of the resale market, both on a personal level and on the business side. Clicking “Add to cart” isn’t the same as nerding out on fashion history with whoever’s working the register at your local thrift shop, and you’re less likely to get a deal on a rare find now that everyone knows what they have. (Morrison wistfully shared a story of nabbing a Givenchy couture gown on eBay for $268.) There are also issues of authentication: Articles in Fashionista and Forbes have pointed out that The RealReal occasionally allows fakes to slip through the cracks of its vetting process—something that could be rectified or minimized if the brands themselves were a bigger part of the conversation.

But we’re still in early days, and the benefits of acknowledging and investing in re-commerce almost certainly outweigh the costs. When it comes down to it, beautiful, well-made clothes should be worn and loved instead of gathering dust in the back of a closet. “Especially at a time like this, when we’re all looking at our consumption, you’ve got to use every item of clothing you buy. Or, at the very least, find someone who will appreciate it,” Morrison said. “If it’s in good enough condition, it should have a life somewhere. It needs to be animated by someone’s enjoyment of it.”

This article was originally published on