Claude Montana, ’80s Fashion Titan and Master of Power Dressing, Dies at 76

French designer Claude Montana, a singular designer who left an indelible mark of the look of the ’80s, has passed away at the age of 76 in Paris. The news was confirmed by the Agence France-Presse who learned of his passing by those around the designer. Montana will be remembered for championing the oversized shoulder silhouette, which continues to be referenced by designers to this day, and dressing woman with a sense of both power and panache.

Montana was born Claude Montamat on June 29, 1947 to a German mother and Spanish father, parents he once described at “very bourgeois” to The Washington Post. They had hopes their son would study something more obviously practical, like his older brother, a chemist. “I didn’t know what I wanted, but I knew it wasn’t that,” Montana once told W in 1979. So, Montana left home when he was just a teen and headed to London. “I left Paris because I couldn’t stand my father’s disappointment.” Once in London, Montana made a living on papier-mâché, designing jewelry out of the grade school-inspired process and selling it to much success, even getting a piece on the cover of British Vogue. When he attempted to bring his goods to Paris, however, the French set was not as willing to accept his crafts, so Montana switched to clothing, persuaded by a friend.

A model in Claude Montana’s spring 1979 show.

At 25, Montana got his first job in fashion, as an assistant at the Parisian leather house Mac Douglas, where he was introduced to the fabric that would later become part of his signature. He learned on the job and, within a year, he became chief designer, and by 1974, he was designing freelance for multiple houses. In 1976, Montana stepped out on his own and held his first fashion show. His early collections were embedded in punk, featuring leather jackets, caps, and pants decorated with silver chains and epaulets. Some were disgusted by this look, calling it Nazi-like. Others, though, were immediately intrigued. Montana denied any fascist influence and kept on the leather track, turning the classic blacks into mustards, reds, greens, and purples in collections to come, with shoulders and sleeves that grew larger and larger.

By the late ’70s, Montana was getting grouped with Thierry Mugler—his one time roommate turned rival—as the future of fashion and the purveyors of a big-shouldered sci fi look once referred to as the “Star Wars syndrome.” But leather was hardly the only fabric in which Montana operated. He also dabbled in cashmeres and silks, always imbuing them with brights colors. Known for being shy and soft spoken, his clothing never matched the designer’s demeanor. He once told the Post he designed for women “who like to make an entrance,” and likely take up space as well. One 1979 collection displayed shoulders so large they “extended half a foot on each side by padding and huge shelflike sleeves,” according to The New York Times.

Models at a Claude Montana fall 1984 show.

It was that same year that Montana launched his own company, The House of Montana, and quickly became synonymous with the ’80s style alongside Mugler. He made himself president of the company, despite having no knowledge of economics. He reportedly spent carelessly, and while his collections were sought after by buyers, the then-fashion coordinator at Bergdorf Goodman described the house as “so disorganized that it was a nightmare.”

In 1985, the Times quipped that Montana “is to big shoulders what Alexander Graham Bell is to the telephone,” as the designer exclaimed, “Shoulders forever!” But in the seasons following, he began tampering down his signature silhouette, and by fall of 1988, shoulders on his clothes were being constructed to match the natural slope of a woman’s upper body.

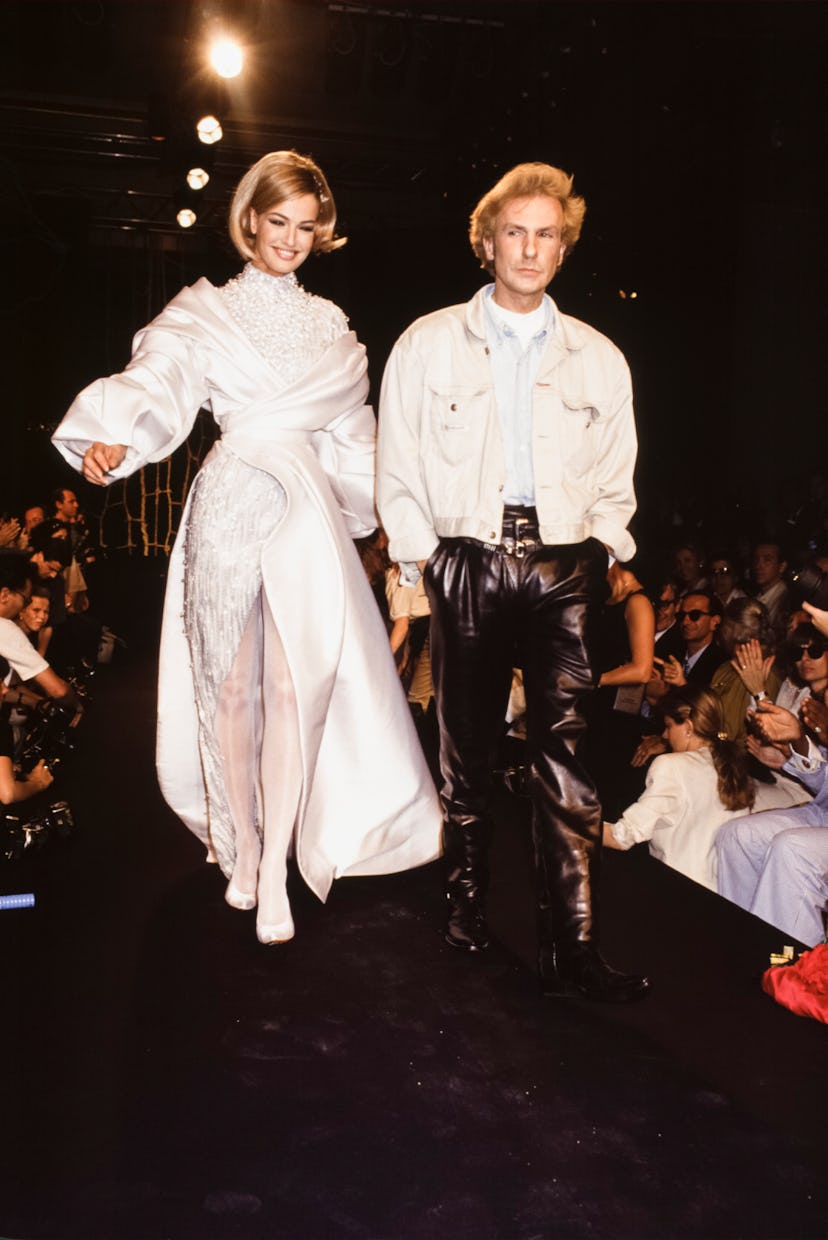

Montana backstage with models during the haute couture fall/winter 1991-1992 show.

After reportedly turning down the opportunity to take over for Marc Bohan at Dior, Montana began designing for couture at Lanvin in 1990, creating a number of collections for the house. “It was a dream to create couture, which turned into a nightmare because of the reviews,” he told Vanity Fair in 2013. Montana brought his aesthetic to the couture runway, sending beaded t-shirts and embroidered leather out at his shows. The press did not respond well to this more casual approach and he shifted for the next season, with more traditionally accepted fabrics, and received much better reviews, but the relationship with Lanvin was already turning sour. Things reached a peaked when Montana refused to design their ready-to-wear collections and was replaced in 1992 by Dominique Morlotti.

In the early ’90s, Montana was at the top of his game with boutiques in Paris, multiple fragrances, and awards touting his name. In 1993, Montana married model Wallis Franken, a surprise among many who new Montana as an out gay man. Many assumed it to be a marriage of convenience between the two close friends, as Montana felt having a woman on his side would be more appealing for buyers. Stylist Olivier Echaudemaison said Montana married Wallis as “a gesture of kindness” as she “had no future left in fashion.” In 1996, however, Franken committed suicide. It was around this time that Montana began to lose his footing in fashion. Many blamed it on drugs and alcohol—Montana was an avid cocaine user throughout the ’80s and early ’90s—while some said that he refused to adapt to the changing trends, as deconstruction and minimalism began to take over the runways. Retailers started to drop his line and in 1997, the House of Montana went bankrupt and he was forced to sell it. Not long after, Montana disappeared from the public world. The man who many considered to be the next Yves Saint Laurent or Hubert de Givenchy was suddenly impossible to even get on the phone. For years, the designer lived at his home in Paris’s First Arrondissement, where he was sometimes spotted, often in manic states.

Franken and Montana at their wedding in Paris in 1993.

Montana will be remembered for both his great highs—his influence on ’80s style and his runway shows that often felt like they existed at the center of the universe. He was also a great influence on many designers who came after him, including Lee McQueen, Olivier Theyskens, and Riccardo Tisci. But he will also be remembered for the lows—the drug and alcohol abuse, money difficulties, and strained personality. In 2013, he reappeared briefly in the public eye, designing three looks as part of his friend, Eric Tibusch’s show. Around that time he told Vanity Fair that he missed fashion. “I really would like to return, but not in the same intense way,” he said, saying it was the bad reviews that turned him off from the trade. “I always took that very personally.” Though British designer Gareth Pugh briefly revived the label for a one-off capsule collection in 2019, Montana never made it back into the world of fashion in a meaningful way, but his legacy will live on. Still today, his influence is seen, on Anthony Vaccarello’s Saint Laurent runway, the exaggerated shoulders at Willy Chavarria, and in Rick Owen’s militant leather work.