Just a little over a century ago, American society in the 1920s shed the woes and trauma of the First World War by drinking out of an endless well of opulence. Prohibition backfired—instead, there were grand parties behind speakeasy doors. Fashion, too, embarked on a tremendous change. Constricting corsets, the hallmark of Edwardian style for women, were suddenly shed from their midsections; dreary workwear was stowed away into trunks, and in came an era of fashionable glamour that, hopefully, would achieve a sense of bliss that had been lost in the years prior.

There emerged an emphasis on simplicity that hadn't been seen before. While women previously reveled in glitz and glamour by donning opulent fabrics, crystal accessories, and strings of pearls, they soon shed all that in favor of the comfort of flowy, loose silhouettes. Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel fashioned the little black dress and, though it was simple, the style exuded sexiness and allure. In that era, the garment was exciting, liberating, and, above all, new.

This newness in clothing—just like any other major moment of fashion invention or reinvention—symbolized a turning tide. The dress itself ushered in new ideas of how women should and could get dressed. Nearly 40 years later, Halston’s novel pillbox hat designed for Jackie Kennedy, which she wore as JFK was inaugurated as president, ultimately had the same effect. Newness in fashion keeps consumers excited and has the power to propel culture, and what that looks like, forward.

When COVID-19 violently shifted our lives nearly two years ago (how dreadful is it to read that?), I recall hearing hopes that a sense of glamour would return to fashion. That some genius, perhaps like Christian Dior, would provide the 21st-century version of the “New Look,” sparked by feelings of doom and despair. While there are still quite a few labels of the moment tapping into Surrealism (Thom Browne's trompe l’oeil abs and Schiaparelli Haute Couture among them), much of what we’ve seen in fashion appears to be quite the opposite of new. All we've seen is the repetition of some ghosts of fashion’s past that are, arguably, neither beautiful nor interesting. They are not even variations of, or added twists onto past trends. Instead, they are exact replicas resold in a new time period.

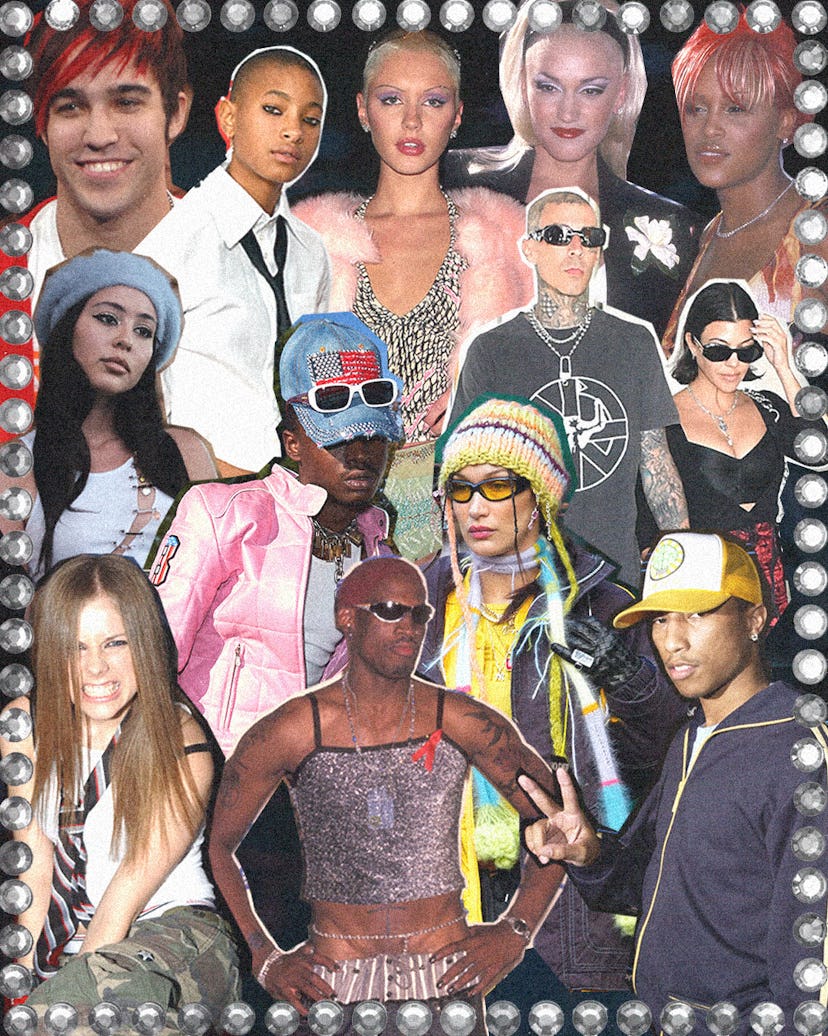

This trend began with Gen-Z’s obsession with the fashion kitsch of the early 2000s—the era of slip-on dresses over jeans, butterfly clips, and small bags came back into fashion around 2019. Then, the throwback trends became more literal. At the start of 2022 alone, conversations about “teenage core,” “kidcore,” and even “gothcore” (when I read that, I was instantly transported back to the days of Hot Topic,) have proliferated both online and IRL. Most recently, there’s been a call for the return of “indie” fashion, a trend that marred the early 2010s with loose beanies, cardigans, and low-slung metallic woven belts. Have we, as fashion consumers, lost all inspiration to move forward into something new? Has the grief of COVID-19 prohibited the search for fantasy? Perhaps the moment we're currently living in is fashion’s era of copy, where the only thing progressive or new are conversations surrounding fashion NFTs, sweatpants, and the metaverse.

Paying homage to a past era is not a novel phenomenon. In fact, it is in fashion’s DNA. “As we’ve become a stronger visual society, it’s easier for styles to be recycled,” Allison Pfingst, program director of Fordham University Fashion Studies and fashion historian tells W. “Gen-Z is also very much interested in secondhand shopping. It is intentional and cool to thrift now, whereas in the 1960s and 1970s it was considered counterculture. Whether or not it is actually sustainable to consume so much is a conversation for another time.”

But Pfingst theorizes that this deep desire to look back to past trends is escapism in a different form. Although she regards these gaudy trends referencing the early 2000s as “an absolute nightmare,” there’s something more than meets than eye happening here. “In this era of fashion, we are constantly looking back at simpler times. Nostalgia is our fantasy and we are romanticizing life when it was easier and tech-free,” she says. According to Pfingst, the chosen trends reflect those feelings with great accuracy. “The era of Paris Hilton’s fashion, the flip phones covered in rhinestones, there’s something juvenile about that time. We’ve been pent up for so long, and in a way, looking back, instead of forward, indicates how many of us have missed out on our youth.”

How can fashion look forward when the youth—the age group from which fashion often finds its muses—has missed out on a pivotal moment in their lives? Many of them didn't get to experience school dances and dressing awkwardly in real life, and have, instead, been forced to live through unrelenting teen angst with not too many social outlets, other than the parties portrayed in shows they're watching like Euphoria. If that's the case, perhaps newness in fashion can wait a little bit. Maybe it should wait a little bit. As many moments of their lives have been forcibly taken out of their hands, perhaps the fashion styles which reflect these stolen times are their last chance to actually live them.

Plus, the effects of becoming a more visually driven society make yearning for the past easier. Throw in a long quarantine and social media as a coping mechanism, and it’s no wonder why images of Paris Hilton, Nicole Richie, and Missy Elliott end up scattered all over designers' mood boards. Nostalgia can travel much more quickly on Instagram and Tik-Tok, where influencers of all sorts are quick to repost.

This experience does not exclude those grew up as part of a different generation. The early 2000s marked a time in each of our lives when problems were small, (even if they felt large at the moment). Issues were not about bills, surviving a pandemic, or fighting corrupt political systems, but more so about the cute boy in fifth period or which surf spot you and your friends were headed to after school. They were simple. Even though the trends of fashion’s era of copy aren’t new, they are doing the same job fashion did in the 1920s and 1960s: allowing us to live in a time that brought us an immense amount of joy.