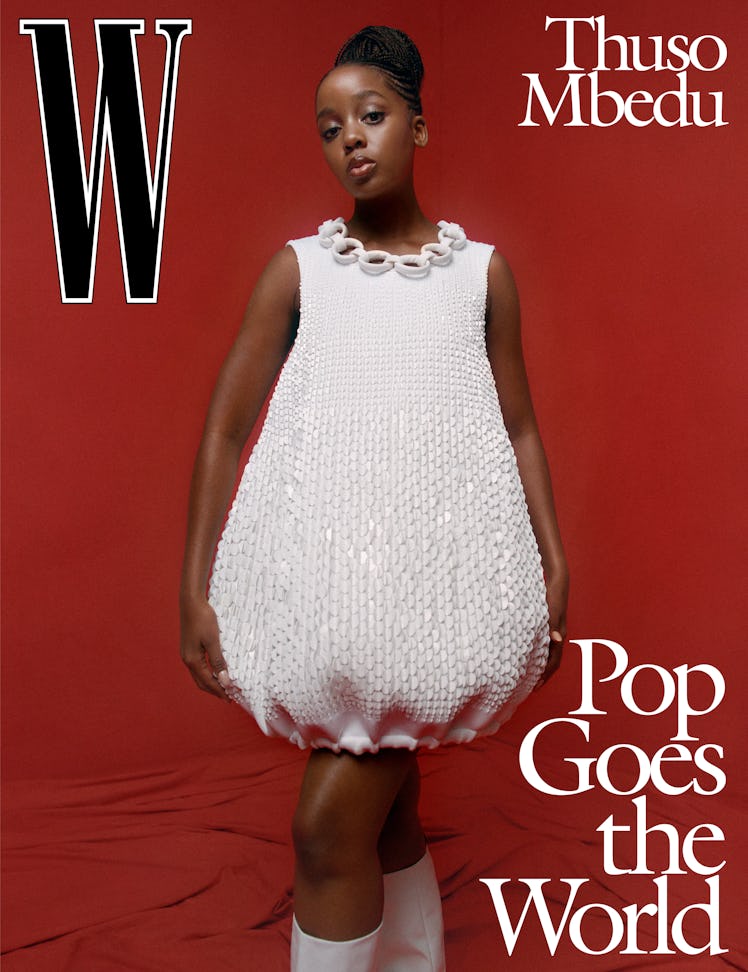

Thuso Mbedu Is Just Getting Started

Her acclaimed performance in The Underground Railroad brought the South African star to Hollywood. Her next project, with Viola Davis, takes Mbedu back home.

As a schoolgirl in postapartheid South Africa, Thuso Mbedu learned only the bare facts about the African diaspora, the Black American experience, and the plunder of her people and their struggle. “It was really glazed over in our history classes,” she says over Zoom. “We were taught that people were taken from Africa, and they were enslaved, and then the teachers sort of just moved on. They do not go into the reality of the Black body in America—the real oppression of the body here. Those are things I only came across as I was doing research.”

That research was in the service of Mbedu’s role as Cora Randall in The Underground Railroad, a 10-episode series on Amazon Prime based on Colson Whitehead’s acclaimed novel, and created, directed, and cowritten by Barry Jenkins. The work is so powerful—urgent in its tenderness and intensity, heroic in its grappling with the nightmare of history—as to constitute a lesson in itself. Mbedu created a monument memorializing slavery and liberation with her performance as a woman who escapes a Georgia plantation in pursuit of freedom and a reunion with the mother who abandoned her. The series literalizes the title of Whitehead’s book, imagining the fugitive slave network as a subterranean train system. On-screen, this plot element achieves special liftoff as a magical realist fantasy, because it is grounded in the strength of Mbedu’s performance.

Bottega Veneta dress; Patricia von Musulin earrings.

Burberry dress and bodysuit; Prounis earrings; Gucci sandals.

That Mbedu was not nominated for an Emmy is the sort of omission that awards show prognosticators call a snub, and critics observe as proof of the limits of the Emmys. The actor herself, however, has her eyes on a completely different kind of prize: “If I’m learning about all of this, then everyone who watches—and I know I have a lot of people from South Africa supporting me—will also be learning these things.”

Before she began performing, Mbedu aspired to become a doctor, and you can hear a scientist’s mind at work in her clinically precise descriptions of Cora’s posture and movements—especially important because the character speaks sparingly. “In episode 1, she’s always hunched over,” Mbedu says, breaking down the arc of Cora’s journey. On the plantation, with its sadistic overseers and unrepentant rapists, “you’re trying to be as small as you possibly can at all times. You don’t want to bring any sort of attention to yourself.” In episode 3, hiding in an attic, she’s “hunched over in a different state.” By episodes 8 and 9, when Cora is living among free people of color and is ready to narrate her full personal history, she assumes the stature of “a Black body with agency,” though with a soul heavy with the memory of those lost along the way. The question for Mbedu became: Where does she carry the world in her body now?

Brunello Cucinelli jacket and pants; Charvet shirt; G.H. Bass & Co. shoes.

Mbedu also went through a systematic process to discover her character’s voice. A dialogue coach helped with the Southern accent, while Jenkins guided her toward audio recordings of emancipated slaves that feature the fragmented language of people forced to stumble through a foreign tongue; an authentic rendering of it would have required subtitles. “How do we find a middle ground?” asks Mbedu. “Hearing their broken English drew me much closer to them,” she says. “In rural South Africa, in certain parts of the townships, some people speak like that. In the recordings, I heard Africans, rather than just African-Americans. I also heard broken spirits, and that changed how I treated Cora. I felt that, as someone who was so withdrawn and isolated, she would use her silence and her voice as weapons.”

Mbedu, 30, was born in a small town in easternmost South Africa, outside a provincial capital, and raised by a grandmother who spoke Zulu at home—except when she didn’t speak to Mbedu for an entire month, after the 16-year-old announced that she was abandoning plans to study medicine in favor of pursuing drama. (Her grandmother had been hoping for a doctor in the family; Thuso’s mother, who died young from a brain tumor, had wanted to be a geologist, an impossibility for a Black woman in apartheid-era South Africa.) Now, having arrived in Hollywood with her first U.S. gig—her Underground Railroad turn universally acclaimed, Oprah Winfrey Instagramming snapshots of their hangouts—Mbedu makes her home in the Valley Village neighborhood of Los Angeles. She arrived at the end of 2020, after shooting on the series wrapped. “I think it’s fair to say that I’m settled,” she says, then pauses. “Still settling.”

Gucci top, skirt, and sandals; Patricia von Musulin bracelets.

During our Zoom call, Mbedu is wearing a Clippers T-shirt that she copped at an NBA playoff game. She offers me a virtual tour of her new home. Pride of place goes to a set photo from The Underground Railroad: Amid a row of cotton plants, with extras playing field hands blurry in the background, Mbedu is in costume as Cora, her round eyes shining with solemnity. Jenkins is standing on a crane platform, reaching out to clasp her hand. The gesture carries an air of solidarity and encouragement, a sense of trust offered and received, and just a touch of a Sistine Chapel fresco feeling, like God touching humanity into existence. In an email, Jenkins remembers it as “the last day of the first block of our shoot.” That is, the final day of shooting scenes set at the plantation where Cora was born—material so harrowing that the production hired an on-set counselor to help the cast through the psychological toll of it.

“On balance,” Jenkins says, “the imagery we filmed on that day wasn’t as hard as on some other days, and yet I looked across the field and could see the burden, the weight on Thuso. As she was passing to move to her spot in the frame, I extended my hand. I didn’t have anything to say; I just wanted to hold her hand a moment to let her know that I was with her, that we all were. I don’t think we said a single word to one another, just held hands and eyes, and then she went on.”

Dior coat; Prounis earrings; Prada shoes.

Louis Vuitton dress.

The actor came to the director’s notice by way of her leading role in the artful South African teen drama TV series Is’Thunzi, a breakout performance that came about at a make-or-break moment for Mbedu. After studying physical theater—“how to tell the story just using the body”—at Wits University in Johannesburg, Mbedu got off to a promising start, stealing scenes in South African TV dramas and soap operas. Then, in 2016, she found herself at a crossroads. “For the first six months of that year, I was not working,” she says. Casting directors, taking in her baby face and five-foot-four stature, considered her too youthful looking. “The feedback was, ‘Your performance is good, but we don’t believe you would sell as a law student in their second year at university.’ It was a real frustration. My savings were depleted, and I went into this deep depression, where I was like, I don’t know what’s next. Do I go back to university and study something else?” The audition for Is’Thunzi coincided with her 25th birthday. “I was like, God, I need you to let this be my birthday gift. Let me get this role. If I don’t get this role, let me just pass away in the night, and I’ll be okay.”

The part—as a city girl displaced to rural South Africa, where she leads a pack of outcasts on a quest—garnered Mbedu international notice. She got information on the role of Cora, and her lines for the audition, late in 2018, while in New York for the International Emmys, her second such best actress nomination. “I wasn’t aware that Barry was attached to the project, and I didn’t know it was based on a novel,” she remembers. “The scenes themselves had everything that I needed.” It was her first U.S. audition. She got the part and bought the book, “and I was like, Oh snap! This is so much bigger than I realized.”

Bottega Veneta dress; Patricia von Musulin earrings.

Mbedu’s forthcoming project—The Woman King, directed by Love & Basketball’s Gina Prince-Bythewood—will take her back to South Africa for location shoots. Her homeland will be a stand-in for Benin, in West Africa; there, an all-female military unit known as the Dahomey Amazons battled against neighboring states and French colonizers until the late 1800s. It was a delight for Mbedu to meet her costar, the eminent Viola Davis, who ranks as one of her acting idols. Mbedu’s Underground Railroad dialogue coach showed her an interview in which Davis explained her process. “Viola said that she puts an emphasis on finding the why of any character—the reason this character makes any of the choices they make. For the longest time, before coming across that interview, whenever people would ask me about my process, I didn’t know how to articulate it,” Mbedu says. “Listening to her, I thought, That’s exactly how I approach my work!”

Mbedu is currently training her body in ways that are unfamiliar even to this young wizard of physical acting: She’s getting a head start on weapons training and martial arts choreography. “I want my fighting skills to be somewhere in the vicinity of my performance skills,” she says. “With the performance, I do all the preparation, and then sort of stow it away and let it live in the moment. I want to get the fighting to a place where it would also come as naturally as possible.” So far, the most arduous work has been with her sprinting coach. “Because I’m so tiny, my character has to have a lot of speed,” she says. “I have to be very fast and agile. Apparently, it wouldn’t be believable that I could potentially punch a person and they’d fall down.” She pauses for a dramatic beat. “I don’t know about that. I would beg to differ.”

Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello jacket, bodysuit, and miniskirt.

Hair by Lacy Redway for Nexxus; makeup by Raisa Flowers for Glossier at E.D.M.A.; manicure by Eri Handa for Chanel Le Vernis at Home Agency. Set design by Mila Taylor-Young at CLM.

Produced by Frankie Berchielli-Jones at Lola Production; production manager: Stephanie Ge at Lola Production; photo assistants: Stephen Wordie, Patrick Lyn, Alex Kalb; retouching: Post Apollo; fashion assistant: Roberto Johnson; production assistants: Klaudyna Astramowicz, Addison Wemyss; set assistants: Caz Slattery, Georgia Coleman, Kate Atkinson; tailor: Lindsay Wright.