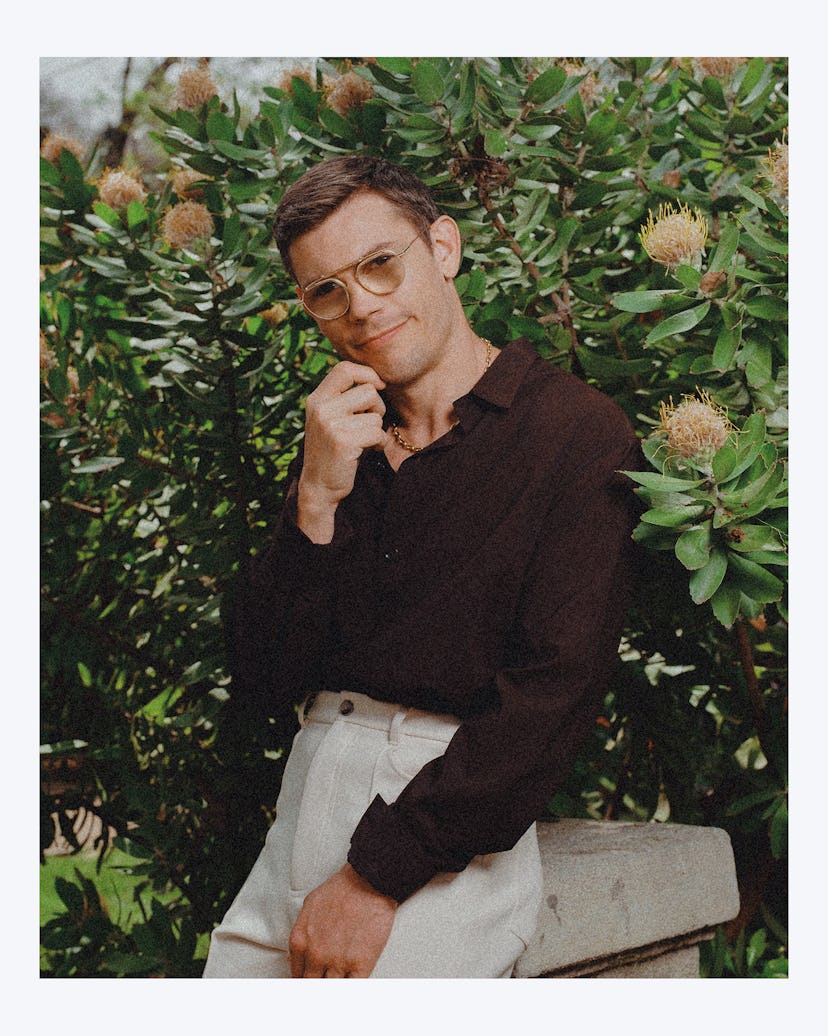

Ryan O’Connell has come a long way from writing viral pieces for Thought Catalog in the mid-2010s, but he’s trying not to overthink it. Fresh off the heels of the second and final season of Netflix’s Special, the Emmy-nominated comedy series he created, wrote, and starred in, he’s now gearing up for his next role: a spot in Peacock’s contemporary reimagining of Russell T. Davies’s Queer as Folk. The series centers on a queer group of friends just like the original did in 1999, but the reboot is noteworthy for arriving to the small screen fully-formed as one of the most diverse shows airing on television today.

For many gay men coming of age in the 2000s, Queer as Folk served as a sexual awakening through its unabashed representation of gay sex and relationships. O’Connell’s relationship to the show was “complicated,” he emphasizes during our Zoom call. “It was my first lifeline to queerness and showing what could be my life if I was an out gay man.” He remembers he would secretly rent the series from Blockbuster and tell his mother he was only watching for the plot. (Others, like myself, would just skip to the sex scenes available on YouTube.) Although the series was transgressive in its own right, the original focused almost exclusively on the experience of cisgender, white gay men. “Being gay, being disabled, it reinforced this idea [for me] that wow…maybe that’s not the intersectional identity I would’ve ordered off the combo menu,” O’Connell says.

O’Connell’s journey to this iteration of Queer as Folk began in earnest in 2019, when he and Canadian filmmaker Stephen Dunn met for a “very glamorous dinner” at West Hollywood’s Sunset Tower Hotel, and got along “like gangbusters.” Dunn, a fan of Special, had just received the green light to helm the Queer as Folk reboot, and wanted to tap O’Connell not only as a writer and co-executive producer for the series, but to his surprise, as an actor as well. “After Special ended, I wasn’t sure I would ever act again,” O’Connell says. “I could not have envisioned being in another TV show, but I’m so glad I did it, and that Stephen believed in me.” To O’Connell’s delight and disbelief, the script included two disabled main characters, rather than a singular, tokenized perspective. “That just speaks to Stephen’s commitment to inclusion and diversity, because very rarely are disabled stories included, but to have two of us on the show was just incredible,” he says.

On Zoom, O’Connell radiates a sense of self-assured confidence and self-awareness. On Special and Queer as Folk, he breathes life into characters that feel grounded and authentic, in part because of his own involvement in the script. “I write things that are deeply personal, and I wonder when that will stop, but the act of writing can be so torturous, so not fun, that I’m doing it as therapy and I can’t imagine doing it in any other way,” he says, adding, “But my life would be easier if I did things that were less personal.”

Appearing in Queer as Folk as an actor is a little bit ironic for O’Connell, who was originally not supposed to star in Special, either. He expresses a sense of imposter syndrome and guilt from falling into the craft rather than obtaining the years of professional training other actors might have. “It’s how I feel about writing,” he explains. “I take writing very seriously, it’s in my blood. And here I was, headlining a TV show with no experience.” With two starring roles under his belt and an Emmy nomination for Best Short Form Series Actor, he’s working through feeling “undeserving”—and has come to find a genuine enjoyment of the process. “Now, having been on Special and doing Queer as Folk, I can actively come out of the acting closet and say, Yes, I do really like it,” he admits.

On Queer as Folk, O’Connell plays Julian, a “sarcastic, dry bitch” type consciously written to feel distinct from Ryan on Special, who is much more tethered to a “gee golly gosh, wide-eyed optimist” disposition. “Julian’s just a very specific character. He’s a person who’s obsessed with the mall and wants to be a flight attendant,” he says. He is joined on-screen by Kim Cattrall, who plays Brenda, Julian’s no-nonsense, very Southern mother. “Being her son truly felt like a gay fever dream,” he says. “I was like, have I jerked off to this before?” (Beyond the surreality of playing her son on TV, O’Connell calls Cattrall “a treat to be around” and “a goddamn delight.”)

Among his many projects, O’Connell is also a published novelist. During the early days of pandemic lockdown, he challenged himself to write 1,000 words per day without any expectations of a final product while waiting for Special to resume its production schedule, “as a way to stave off existential dread,” he says. In just three months, he completed a solid first draft. “There’s no chic way to say it; it just poured out of me,” O’Connell says. “It felt like an exorcism. I will be chasing this high for the rest of my life.” On June 7, Simon & Schuster published the end result of his pandemic experiment in the form of a novel, Just by Looking at Him, a “traumedy” about a gay TV writer with cerebral palsy struggling with an alcohol addiction and deep-seated unhappiness.

Writing the book was deeply personal and therapeutic for O’Connell. “The character is a high-functioning alcoholic,” he explains. “At the time I had a really bad problem with alcohol that I needed to change. I knew [I was] voicing feelings that I’d never given myself permission to voice in the mouth of this character. When you see, you can’t unsee.” Halfway through writing the novel, O’Connell got sober. However, he wants to be clear that Just by Looking at Him is not a memoir like his first book published in 2015, I'm Special: And Other Lies We Tell Ourselves, one he does not look back on fondly. “I mean, don’t give a 26-year-old a book deal. They cannot be trusted. They’re unwell,” he says semi-jokingly.

O’Connell has now developed a hunger for the entire creative process, from acting to writing and producing, and he hopes to eventually mentor and mold new voices for the screen. He will not, however, watch scripted television in his free time. “Honey, I work in TV,” he says. “When I watch TV, I need to be fully lobotomized. Watching scripted TV for me is like doing fucking homework.” For now, O’Connell says he’s in his “gay disabled era, creatively,” and he hopes Queer as Folk helps queer people feel seen as it tackles inclusion in a way that feels authentic and centers characters that have been historically relegated “to being the appetizer,” he says. “It feels corny but it’s true: representation matters.”

This article was originally published on