Russell Tovey’s Documentary Life Is Excellent Fills In the Gaps on Queer Art History

When he was a teenager, Russell Tovey found himself terrified when he flipped on Queer as Folk and saw a scene involving what the Sex and The City girls might call “tushy lingus.” Now, as an adult, you’ll find few other actors as dedicated to exploring all aspects of the gay experience as Tovey. He’s co-starred in HBO’s Looking, the recent leather bar-themed iteration of American Horror Story, and next year he’ll play Truman Capote’s partner in the second season of Feud. On stage, he’s starred in The Laramie Project, the Royal National Theatre’s 2017 production of Angels in America, and, earlier this year, a live reinterpretation of Derek Jarman’s landmark film Blue. But Tovey knows his opportunities to take those roles as an openly gay actor can’t be taken for granted. “I feel such a responsibility to look back at who's done the work so that I can stand here today and say that I'm gay,” he says. “I feel the utmost respect for the generations involved in activism and protests to earn our rights, get representation, and amplify and encourage more people to be free.”

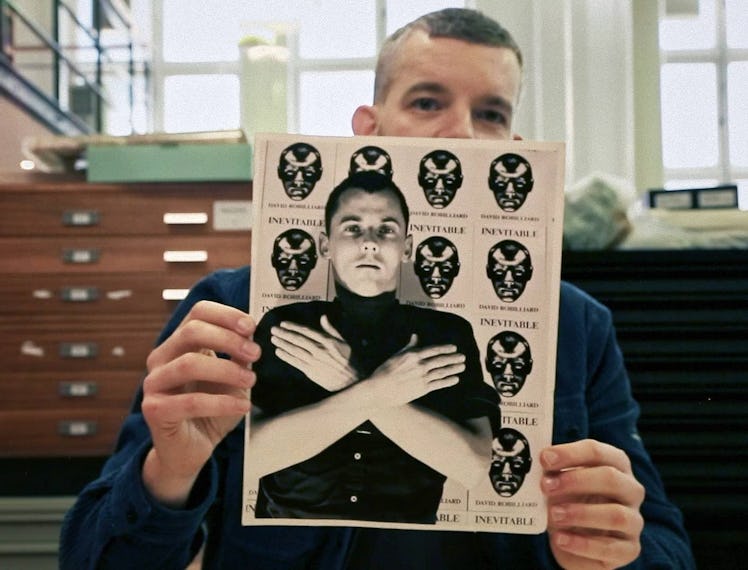

Outside of his acting work, he’s taken up the cause by championing queer visual artists (mind you, he’s also a serious art collector and has co-hosted the podcast Talk Art with friend Robert Diament for the past five years) with a specific mission of highlighting artist we lost to AIDS. That’s all led to Life Is Excellent, the first full-length documentary produced by WeTransfer’s WePresent platform that follows Tovey as he retraces the life of British artist and poet David Robilliard who died at just 36 in 1988. Tovey talks to Robilliard’s surviving friends, lovers, and frenemies, visits his hangouts, and explores his work, while notables like Bimini Bon Boulash, Princess Julia, and Harry Trevaldwyn appear to recite Robilliard’s poetry.

The documentary is now streaming for free. Below, Tovey talks about why Robilliard’s story fascinated him, watching queer movies as a teen after his mother went to bed, and Andy Warhol’s nude photography.

For gay men of a certain age, you look back and think there's a whole generation of people who could have been mentors, friends, and role models that are just gone. I'm interested in what led you personally to find out more about artists that we lost during the AIDS crisis.

Culturally, I've always been drawn to stories or artists that were around in the Eighties. I was born in ’81, and when I started realizing I was gay at 15 or 16, I was terrified of HIV/AIDS. For me, it was like every time you went to bed with someone, death walked into the room with you. It’s a generational trauma that we've all had. The art that I was looking at around that time were things like Angels in America and artists like Robert Mapplethorpe and Keith Haring. The more that you uncover artists like that the more that little doors open and they introduce you to other artists. Queer art has always sort of been othered. I remember being younger and finding a postcard book of Tom of Finland and being equally fascinated and terrified of it.

Recently, there's been a real boom in queer artists being commercially successful, which has never really been the case before. These artists haven't come out of nowhere. And all these queer artists I speak to on the podcast and know in real life always revert back to artists that have gone before them, but there are all these gaps. So I've always been inspired to make sure that the gaps are filled. These artists, and there are lots of them, their stories were cut short, but it doesn't have to remain that way.

How did you first come across David's work? Why did it resonate with you?

I think it was at the ICA in London. I discovered him when I was like 36. He died when he was 36, which was a terrifying notion. I'm not ready to go, and he wasn't ready to go. I remember seeing the exhibition at the time and thinking, Wow, this was a guy who in the ’80s was making this work that was so clear in his message and so gay I was like, “Well, what the fuck is this? Where has this been? This would help me.”

I made the documentary because I just wanted to know more about him. There wasn't enough out there, but there were still people alive who knew him, slept with him, were best friends with him, maybe didn't like him, but were touchstones in his life. So it felt like an absolute must to explore that.

There's still so much available to discover about that generation, but the time is slipping away.

They felt like they were running out time and I feel like we're running out of time to record the stories with people who were there that knew them and can speak clearly about that time. It's such a sensitive thing to approach people who lived through it because it was hell. It feels like only recently that people are ready to talk about it because enough time has passed. It's still painful, it's still terrifying, and it's still very triggering for so many people.

It also seems like so many of the people who have gotten their due were those who were already established with mainstream appeal. But there are so many stories that were cut short, or maybe their appeal would only resonate strongly with a queer audience.

People are ready for it now. There are artists now that are so out and proud. The imagery within their work is so queer; artists from the ‘70s, ‘80s, and earlier were making this work, but it was hidden. There was also a certain legality with some of these works that were being drawn or photographed. I heard a story about Andy Warhol's dick pics that he was taking. He could have gone to prison if they'd been intercepted. If someone would've seen the fact that he was sharing these images, which were art, he would've been arrested. These works just existing in the world is political, and I fucking love that.

Was there a piece of media that first stirred the queer identity within you?

I saw a movie called Beautiful Thing when I was 15. I was living at home with my parents and it was on Channel 4. It was about two young lads on a housing estate who fell in love. I was watching it, my mom was upstairs and told me to go to bed, and I turned the TV off. She went to bed and I put it back on mute and I was like, “That's me. That's who I am.” It made such a difference.

Then when Queer as Folk came on in the UK, it terrified me. I remember the first episode, there was a rimming scene. I was like, “What the fuck is going on?” I had no idea what that was. It was terrifying, but so “wow!” The show felt like a light shining. I'm going to look at that light. I'm going to head towards there because that seems like a safe ground and it's going to explain all the things that are going on in me.

And any visual arts?

The photography of Nan Golden and the photography of Wolfgang Tillmans. I was introduced to them by someone that I was having this mad affair with when I was in my early twenties. I remember going, “fuck, look at this!”

Nan Golden was documenting her friendships in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Just the most moving, upsetting photographs of her friends deteriorating and the way she documented them. Cookie Mueller and all these people were being introduced to me through these images, through these friendships. And then artists like Jack Pearson, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Robilliard, David Wojnarowicz.

What's the best gay movie you've seen recently?

I like Passages. I thought that was brilliant. I saw All Of Us Strangers, Andrew Haigh’s new movie, that was fucking powerful.

I watch documentaries constantly. Recently, I'm watching every interview that Francis Bacon's ever given.

Derek Jarman has become big for me. I remounted his last film, Blue, but I’ve gotten into his writing. In his diaries Modern Nature, and I quote this all the time, he said, “If you wait long enough, the world moves in circles.” That felt so profound because he was writing that in the ‘80s. Now here we are again where homophobia is back, but it's been replaced heavily in the tabloids by transphobia. I sort of remember how that was in the ‘80s. As an adult I have more of an opportunity now to say something and do something about that. I don’t konw if you heard of something called Section 28, but it was put into the British education system by Margaret Thatcher, and meant you weren't allowed to promote homosexuality within education.

So I'm of that generation—if they thought you were queer, the teachers weren't allowed to discuss it with you. You came out of school feeling already ostracized by society, already not accepted, didn't know where you fit in. All of these things now feel like that could seep back into education.

I'm originally from Florida and they've reintroduced those laws there recently. So it is, like you said, things repeating themselves.

You take a step forward, then it's two steps back, but you keep having to push forward. My way of doing that, and my contribution to that is through art. It's through the roles that I take as an actor and the choices I make, the things I write about, but also through the podcast, through who we amplify, through who we encourage people to be interested in.

Inspired by the rimming scene—but also all the art you've talked about—there are some people who might want to water down representation, but in your work and the work you're highlighting here, it feels like you want to go there. Is that important to you?

I don't want to present a sanitized version of things. I think there's a two-pronged approach to this. I've been really considering this recently because the way that you connect with as many people as possible is you tell the story of someone's existence and make it as universal as possible.

I worked with Andrew Haigh on Looking and we were just talking about his new film. He’s able to show intimacy in such a way that you don't see anything but everything's happening. It makes it so universal. I want to tell stories that connect to as many people as possible, but I also want to go fucking hardcore and talk about the piers and Alvin Baltrop and all those stories.

I assume you’ll have to consider each piece of work on its own to figure out whether you should go the intense route or not.

I think of my mom listening to the podcast. My mom's very open-minded, but if you'd start talking about hardcore stuff on the podcast, which I do, I know that my mom might find it a bit like, “All right, calm down.” And that’s great. That’s part of it.

At the same time, someone else is listening to it thinking, “Oh, I’m not as much of a freak as I thought, that experience is actually completely normal.”

Exactly. I’m trying to find that balance. The minute you start making work you deciding what to put in and what to take out, you’re an editor. It's quite interesting, and I'm really enjoying the process of it.