Directing Summer of Soul Taught Questlove to Believe in Himself

One week before Questlove’s directorial debut, Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), was due to hit Hulu on July 2, and after it had just been released in theaters, the multi-hyphenate appeared on a Zoom screen, ticking off the major artistic milestones in his life.

“I’m an 11-year-old at Radio City Music Hall, and my dad is telling me, ‘Alright, well, you got to drum now because the drummer’s injured, go on stage.’ No sweat,” he says, punctuating his commentary with a whistle. “Tariq [Trotter] telling me, ‘Let’s take a bucket on South Street in Philly and busk to see if people like our music.’ No sweat. Telling my dad I'm not going to Juilliard and getting a record deal, no sweat. Leaving all that behind for late night television, writing a book, teaching at NYU, no sweat whatsoever. But for some reason, when this movie came into my lap, I was like woah, uh-uh. This is too much. I don't know if I'm the guy for this."

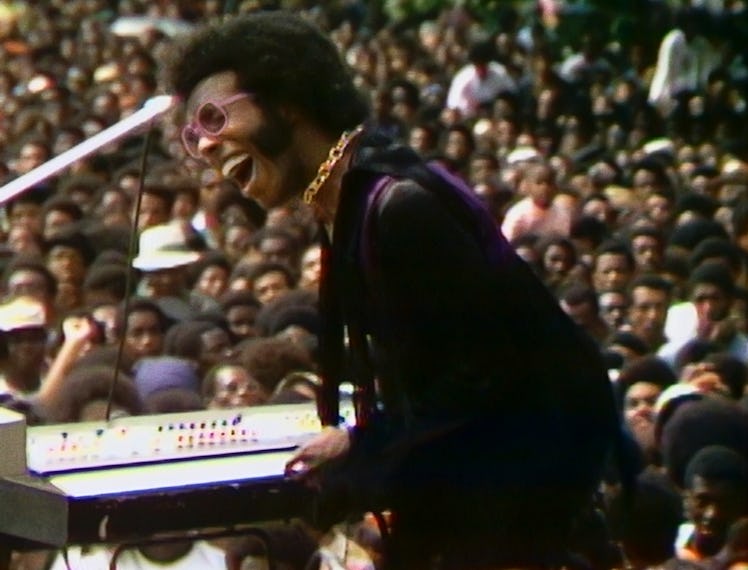

The reasoning behind any trepidation felt by Questlove, born Ahmir Thompson, is understandable. The film was compiled from 40 hours of footage from the Harlem Cultural Festival, a spectacular concert attended by thousands that took place over the course of six weeks in 1969. Woodstock occurred the same year—and has taken its place in history as a monumental show. But the Harlem Cultural Festival was worth its salt, too: Nina Simone, Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder, Gladys Knight, and Mahalia Jackson were among the performers from June 29 to August 24, 1969. The republican mayor at the time, John V. Lindsay, also made a speech at Mount Morris Park (which is now named Marcus Garvey Park,) as did the Reverend Jesse Jackson. The Harlem Cultural Festival was a celebration of Black and Brown artistry during the crest of the Black Power Movement. Yet it disappeared from the public's memory for decades.

Tony Lawrence hosts the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969, featured in the documentary SUMMER OF SOUL. Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures; 2021 20th Century Studios.

According to Questlove, "Very few people knew this footage existed,"—save the concert's producer and videographer, a man named Hal Tuchin, who had shot the entirety of the festival and spent years shopping the flick around to television and film networks as what he dubbed the "Black Woodstock."

"There was a point in 1979 where he just stopped trying to peddle this film," Questlove adds. "He kept going over and over again, recontextualizing it—half those stars became household names by that point—and still no interest. So it just sat in his basement in Upstate New York." Questlove's two producers, David Dinerstein and Robert Fyvolent, approached Tulchin before he passed away in 2017, hoping to buy the footage. Tulchin held on tight to it, until about a week before he died.

"I do wonder what effect this film would have had on me, had it come out in real time—the same way that Woodstock affected people, could that have changed my life? I know I wound up being a musician anyway, but I'm sure there are 4 billion other people whom this one could affect in a different way,” Questlove says. “And I wonder about them. Could this have made a paradigm shift in their life?"

Nina Simone performs at the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969, featured in the documentary SUMMER OF SOUL. Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures; 2021 20th Century Studios.

Gladys Knight & the Pips perform at the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969, featured in the documentary SUMMER OF SOUL. Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures; 2021 20th Century Studios.

For the musician, timing is everything (at one point in our conversation, he wonders if Michael Jackson's Thriller would have had the same impact if it didn't come out on November 30, 1982—when MTV was in its prime, playing music videos all day long. "The answer is sadly, no," he surmises). And Questlove is cognizant of the fact that Summer of Soul will be screened at the perfect time—after people have spent months cooped up at home, longing for live music, and at a juncture when movie theaters are finally opening back up. (Questlove watched the movie in theaters for the very first time last week during the premiere in Harlem, because he wanted his “first experience [watching the full film] on loudspeakers in a theater.”)

Hugh Masekela performs at the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969, featured in the documentary SUMMER OF SOUL. Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures; 2021 20th Century Studios.

There was just one accolade Questlove didn't mention when he was rattling off his landmark achievements: launching Okayplayer, the music blog platform upon which he shared personal stories of his run-ins and experiences with fellow celebrities, from Beyoncé to Prince and Patti LaBelle. I ask Questlove whether this tendency to want to chronicle his life and the lives around him contributed to the desire to work on Summer of Soul, too. He says his friends and family members, and most of all, his girlfriend, reminded him that his abilities and strength already existed within himself.

"I had to take a kind of metaphorical cliff jump to get to a new level of creativity," he says. "The reason I had trepidation with making this film is simply because this was more than just a movie. I was being told that I have to restore history—it felt like I'm at a foul shot during the playoffs with one second left and the ball has to go in the basket, and can I do this? But I'm smart enough to listen to my ledge-talkers. I'm always on the ledge, ready to jump, ready to end it all. And there's someone always like, Amir, come back inside. You can do this, breathe. That was the process."

"This film taught me more about myself as a human being, than as a creative," he adds. "And now it's never going to leave me. Anything I do creatively or personally will always be in the guise of me facing the fear of this film. I'm never going to be the same again."