Ming Smith Relives Her Famed Works, in Her Own Words

Ahead of the photographer’s first solo exhibition at a major institution, Smith tells the backstories behind some of her greatest images.

On May 25, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston opens “Ming Smith: Feeling the Future,” the photographer’s first solo exhibition at a major institution to survey her work from the early 1970s to the present. Curated by James E. Bartlett, the exhibition will emphasize the photographer’s post-production techniques (painting, sumperimposition, etc.) that lend a distinct aesthetic and underline a certain message in her portraits of Black life. In addition to the street photography for which she is well-known, Smith has snapped some of the greatest Black entertainers over the years like Grace Jones, Nina Simone, Tina Turner, and Alice Coltrane. These come up often in her oeuvre, as she cites music as the greatest source of inspiration—jazz in particular, which reflects the improvisational nature of her work. Ahead of the opening, Smith spoke with W magazine about a selection of photographs featured in the show, which will be on view through October 1, 2023, including the backstories behind some of her most famed works.

Transcendance, Turiya, and Ramakrishna

Ming Smith, Transcendence, Turiya and Ramakrishna, for Alice Coltrane, 2006.

“I was doing a series on Harlem Gardens. I had a friend, the late Joyce Dukes, whom I told that I wanted to a project with nudes and visual femininity. I wanted a Black woman and I said, ‘Maybe next year,’ and she says, ‘Well, I’ll do it now. I’ll do a nude for you.’ It was very spiritual, actually, the photographing of her. A young man was sitting on the fence and he came up and said, ‘That was the most beautiful experience to watch you photograph.’ It was a young man who didn’t talk about the nudity, but the experience—and that meant so much to me.”

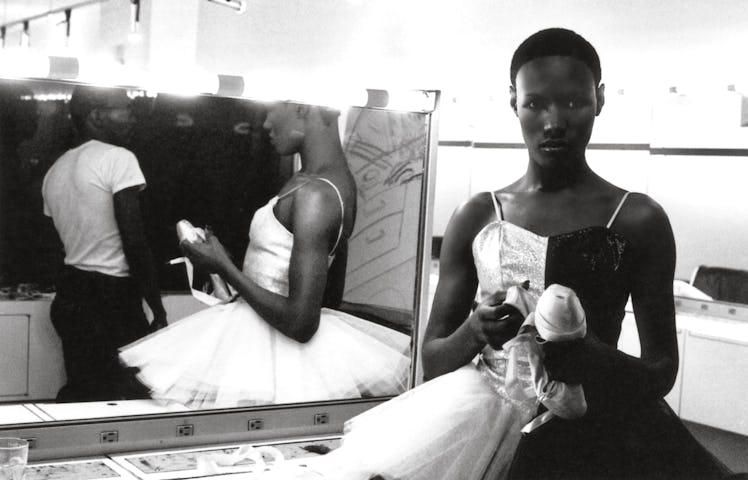

Grace Jones at Cinandre’s

Ming Smith, Grace Jones at Cinandre, 1974.

“I went to get my hair done or make an appointment at Cinandre’s, which was a hair dressing place on 57th. It was the contemporary, ‘who’s-who’ place to get your hair done. Everyone talked about how he was a genius. Grace was actually there that day trying to get Andre to cut her hair in the flatop that she’s famous for. We were both aspiring Black models, so we talked about how we fit in or didn’t fit in, about being to exotic, etc. I had my camera there, so I took photographs of her. She went to Paris not long after and became a big hit with her music.”

Acid Rain (“Mercy, Mercy Me,” Marvin Gaye)

Ming Smith, Acid Rain (“Mercy, Mercy Me,” Marvin Gaye), 1977.

“Acid Rain was a series I did in New York and it was dealing with pollution and climate change. They used to call it acid rain and the big hole in the ozone. Then I heard ‘Mercy, Mercy Me’ by Marvin Gaye and he sings about the same things, so that’s why it was dedicated to him.”

America Seen Through Stars and Stripes (Painted), (New York)

Ming Smith, America Seen Through Stars and Stripes (Painted), (New York), 1976.

“That was taken in 1976, which was the Bicentennial of America. But it deals with this person seeing what was really going on in America as far as Black people were concerned. I painted that one to emphasize the bloodshed of what had been done and what is being done to Black people.”

Prelude to Middle Passage (Île de Gorée, Senegal)

Ming Smith, Prelude to Middle Passage (Île de Gorée, Senegal), 1972.

“I think this is kinda funny because we all know about the Middle Passage, but there was a Senegalese travel guide and I told her, I’m new in the world, and I asked about polygamy. There was a lot of political unrest and American Black men were saying that they believed in polygamy because that’s what they did in Africa. I was very curious about what she thought of that, and she told me ‘We don’t play that!’ That’s the old way. It’s 2023, and I know so many young African men that have a wife in Africa, a wife here, and maybe a cute girlfriend. She might not have played that, but it’s still happening today!”

Sun Ra Space I

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space I, 1978.

“I’m a big advocate of dance—I still dance, and I danced back then. One of my friends who was studying belly dance said she was thinking of going to dance with the Sun Ra Orchestra. She asked me if I wanted to go along with her to check it out. I decided to go—and that’s when I took those photographs. But it was just to accompany her for emotional support. I remember really not wanting to go, but then look what happened. I not only made money, but I made history with those photographs. Karl Lagerfeld said it was his favorite photograph. I was looking forward to meeting him, but he passed.”

Goghing With Darkness and Light (Sunflowers), (Singen, West Germany)

Ming Smith, Goghing with Darkness and Light (Sunflowers), (Singen, West Germany), 1989.

“So I’m on a bus going across Europe with my ex-husband, his octet, and a few other jazz musicians. We had been traveling for at least six or seven hours and saw these fields of sunflowers. I was like, I’d love to photograph those. All the men were hungry and tired, but I had to muster the energy to ask them to stop for two minutes—I see a photograph that I just have to take. Of course, Van Gogh would paint sunflowers because they’re just so beautiful. I felt that connection. You don’t understand until you’re there. I hopped out of the bus, took the photographs, went back, and was so relieved.”

Mother and Child

Ming Smith, Mother and Child, 1977.

“This is probably one of my earliest photographs, when I first started shooting on the streets of Harlem. The image of Harlem and Black people was always poverty and violence. It was a lot of shame, and the visuals representing this didn’t really tell the story of Harlem because it’s a very warm place where people live their entire lives. I saw this image of a mother and child. She was poor, obviously, because she didn’t have a phone in her house, so she was using the phone booth. The daughter was clinging to her and the mother looked like she was missing someone, or she’s asking for money. There was something going on where she was very involved in the conversation. That image spoke to me.”