How Fran Kranz Created a Subtly Spiritual Meditation on Grief

Earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival, Mass, an intimate drama about two sets of parents who meet years after a violent tragedy, emerged as a a must-see. The film opens with a parish worker (Breeda Wool) fussing about the setup in the basement of an Episcopal church while a professional mediator (Michelle N. Carter) tells her to remove the snacks and place a box of tissues in just the right spot. It is soon revealed that the reason they’re there is to faciliate a meeting between with four parents—played by the impeccable Martha Plimpton, Jason Isaacs, Ann Dowd, and Reed Birney—to discuss the mass shooting that took the life of Gail and Jay’s (Plimpton and Isaacs) son, and which was perpetrated by the son of Richard and Linda (Birney and Dowd). The question that hangs on every sentence uttered by the four bereft parents in that room over the next two real-time hours: Is forgiveness is really possible after an unspeakable act of violence?

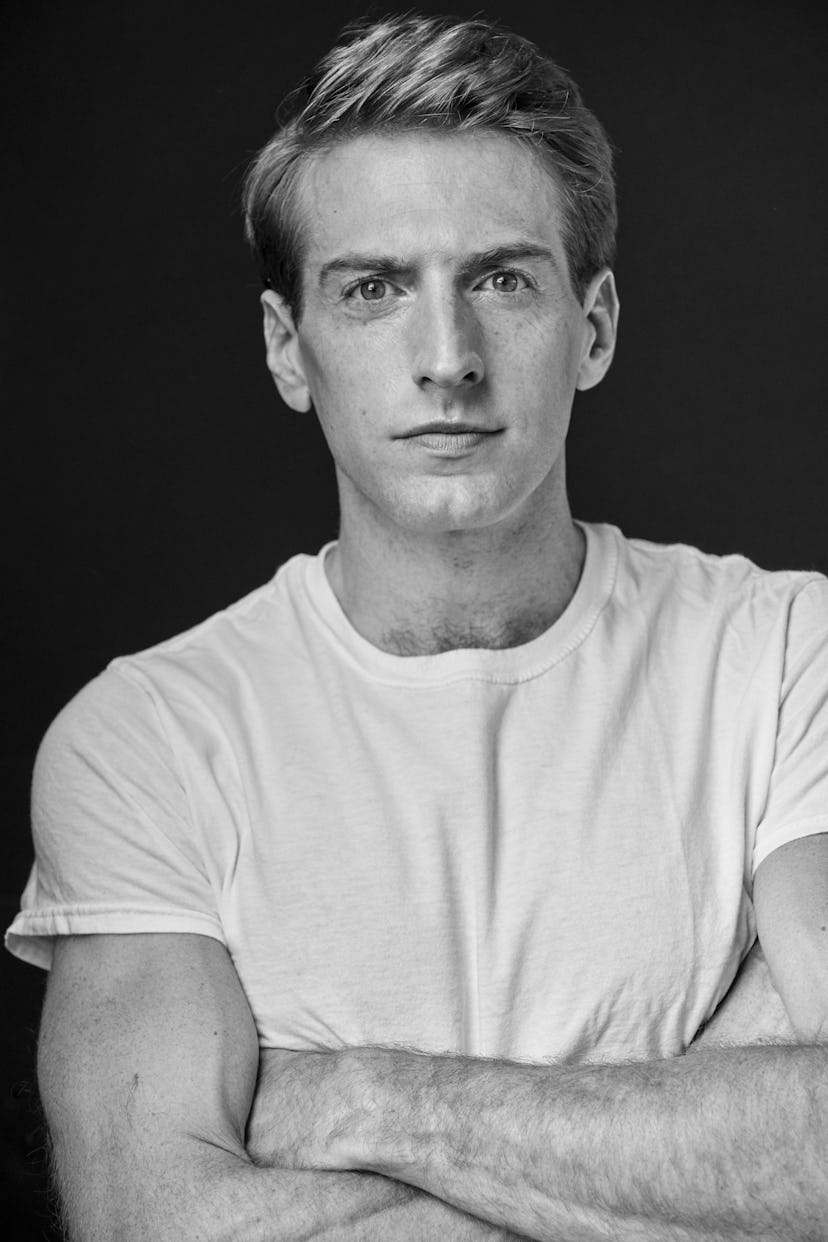

Fran Kranz, who wrote and directed the project, which will be released in theaters on October 8, says he first started thinking about it after 17 high school students were killed during the Parkland shooting on Valentine’s Day in 2018. “Children are not present [in the film], but so much of it is about them,” he said on a Zoom call from Washington, D.C. last month. Kranz, who is best known as an actor, had never written and directed a film until Mass, but had appeared in plenty of film, television, and theater credits as an actor, most notably Mike Nichols’s 2012 revival of Death of a Salesman. (Nichols’s familial approach to encouraging actors to bond before performing, Kranz later explained, would turn out to inspire his own ability to draw out the necessary intimacy from the four main actors in Mass over the course of a two-week indie film shoot.)

Parkland was the first mass shooting to garner national attention since the birth of Kranz’s daughter, and it struck a nerve. “It really upset me in this whole new way,” he remembered. “I remember where I was when Columbine happened and I was the same age as the shooters, and it scared me. It was an upsetting world shift for me to be that same age and be at school and look around at the world with this new perspective.”

Suddenly the actor, who had always wished he would turn one of the stories he had in mind into a film, found himself ordering books about mass shootings on Amazon, studying the motivations of school shooters and the devastating effects on the lives of gun violence survivors. The film, he said, came about “out of a newfound empathy, compassion, and obsession with what was happening because I find it to be inexcusable and it seems shocking to think this has continued fairly undeterred for 20 years.”

“It should feel personal,” he said. “This is a credit to some really incredible journalists, but also the vulnerability and openness and honesty of the individuals in these communities and survivors who talk about it. We’re not taking it personally enough. We don’t know their names as well as we should,” he continued, getting a bit choked up at the thought of gun violence statistics. “You learn about what these kids were doing and what they were wearing to school that day, wherever they were planning to go to college or their summer plans, you get these details and it destroys you.”

“I thought, Maybe there’s a way to sort of capture some of this intimacy and this personal knowledge—fictionally of course—as a way to cultivate and inspire greater empathy in audiences and our society in general, because maybe that is something that’s missing,” Kranz said. That intimacy is key in Mass, which takes place in real time. Once the film begins to unfold, it becomes quite clear that the title is a double entendre, referring not only to the type of violence inflicted upon the families grieving, but also a reference to the site of mediation.

Kranz, who is not religious but was inspired by Desmond Tutu’s No Future Without Forgiveness, felt that placing the characters in a church was paramount to his mission of getting people to engage with forgiveness and reconciliation, while also giving the film a spiritual, but not necessarily theological, bent. “I’m paraphrasing, but Tutu essentially said that forgiveness, reconciliation, and reparation are not the normal currency of political discourse. These ideas exist in a spiritual or theological realm,” he explained. “To me, it had to be in a house of spirituality or worship. And in fairness, some of the meetings I’d read about did take place in a house of worship.”

“I believe it already does raise spiritual questions about the explicable and the mystery of life, and life and death in general,” he went on, pointing out that each character’s different relationship with spirituality was purposefully written so that audience members could find someone to relate to in the story no matter their personal perspectives.

As I wondered if he might ever adapt Mass into a play, considering the constraints of the location and the dependence on gut-wrenching dialog from these four exemplary performers, Kranz informed me that it actually started out that way. At first, it was a 60-page script meant for the stage, until the limitations of getting a play to debut Off-Broadway got in the way. “I felt really discouraged and thought, wait a minute, this is one location and I bet we can make this for $100,000 dollars,” he said. “My heart was always set on a movie and I knew I would get it done much faster if I make the movie. And so I did.”

Time of the Wolf, Michael Haneke’s 2003 post-apocalyptic family drama starring Isabelle Huppert, served as a bit of cinematic inspiration for Kranz—not aesthetically, or even narratively, but in terms of the feeling he felt when he first saw that film. “It ends with such an incredible combination of bleakness and hope, and the mystery of that, the sort of paradox that that is, that feels so like the human condition,” he explained. “I wanted to capture a feeling like that.”

“I really hope the survivors in these communities feel like I’ve paid attention and cared about the personal level of all of this,” Kranz said in a final moment of reflection. “Hopefully I can make more people pay attention to that—that would be a really positive outcome of it all.”