Yasmin Kara-Hanani, the young, bold investment banker on the HBO and BBC Two series Industry, recently tried to level with her manager.

“We’re all cunts, aren’t we? So let’s just lean into it, yeah?”

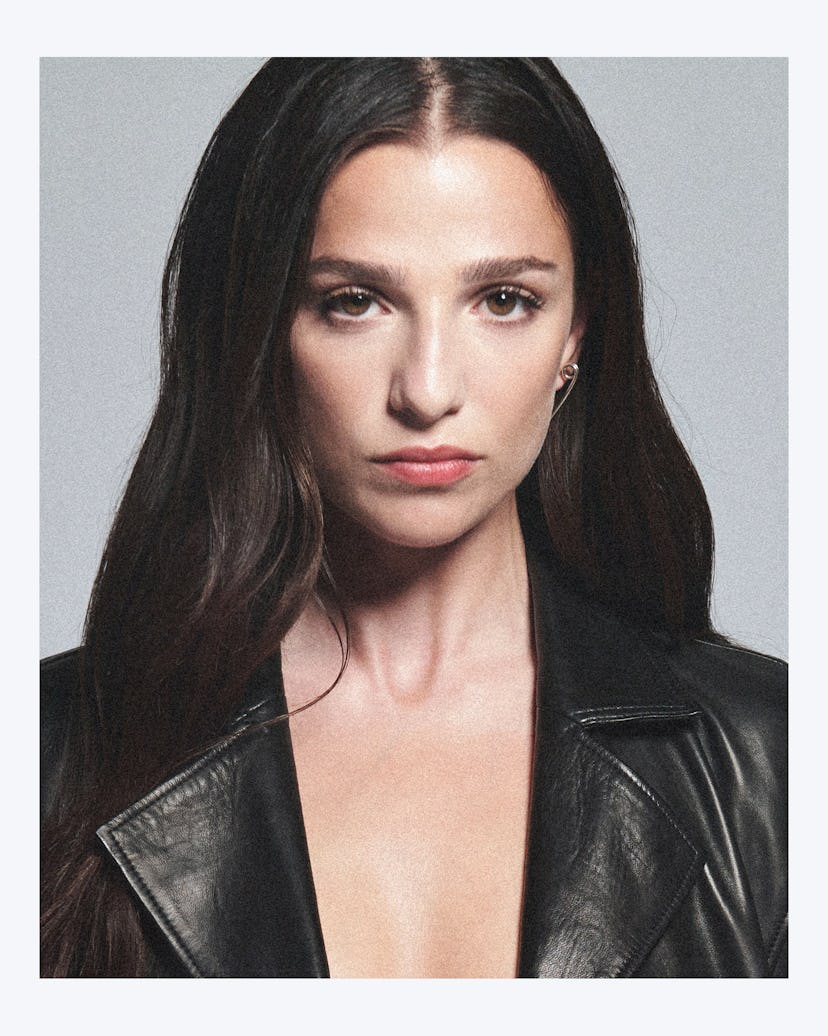

It’s a stunning line, delivered with delicious confidence by Marisa Abela, the 25-year-old who plays her. No one would accuse the English actress of that—or of sharing her character’s radiating ruthlessness—but she is entirely in command, and certainly leaning in.

Look at Abela’s career trajectory: Before even graduating from the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA), one of the world’s most prestigious acting programs, she’d shot a recurring role in the action series Cobra and was already working on Industry. (She sent selfies with her graduate degree to Lena Dunham, who directed the series’ pilot.) As its second season snowballs more viewers and attention on social media, Abela wraps work on Greta Gerwig’s buzzy Barbie movie, and is in early talks to play Amy Winehouse in the upcoming Back to Black biopic—a prospect she is hesitant to discuss, but has her fingers crossed.

“If you’d have told me that by the time I was 25 I’d have worked with Lena Dunham and Greta Gerwig, I’d have geeked out,” she says. “It’s just inspiring, working with these women who have crushed it in the most ultimate way.”

Just as those two women, and just as her character on Industry, which streams on HBO, Abela understands the trials and benefits of hard work. Born in the arty coastal town of Brighton to a stage actress mother and a comedian-turned-director father, the actress knew firsthand what she would be up against if she pursued acting. She jokes that her parents warned, “Unless there’s nothing else you can do, don’t do it.” This led to a brief period—her “rebellion,” she calls it—where she intended to become a human rights lawyer.

Marisa Abela and Adam Levy on Industry.

Her showbiz genes ultimately won out, and she wound up in London, albeit a very different one than the money-hungry metropolis portrayed in the series. While Yasmin is made to suffer all kinds of harassment from her toxic higher-ups, Abela knew that enduring a bit of humbling during her acting training would strengthen her chops, something she says helped her clue into a finance world about which she had no idea.

“You do these objectively humiliating exercises in both,” she says. “If you want it badly enough, you have to blindly trust that pretending to be a giraffe for 2 hours on a Monday morning is going to get you where you need to go. Not that it was a bad time—I had an amazing time at RADA—but, you’re crawling around like a dog… literally. You might be metaphorically crawling around like a dog in finance, but you are actually doing that in acting school.”

The giraffe comment refers to an exercise she did during her studies—the large animal assigned to her because, she says, it’s far from who she is: smaller, more cat-like, “less gracious.” I suggest that, despite her 5’5” stature, she seems to have a large enough presence, and that cats are among the more gracious animals; she replies they’re graceful “in a different way.” Her instructors, she says, “wanted me to be more above it all.”

“There’s this unwavering belief in both [finance and acting] that your superiors know everything,” she says. “I think it’s why you can only come into a career like these if you start very young. Because in order to put up with the bullshit at the beginning, you have to be young enough to think it’s acceptable.”

Her own youth informs the way she is able to view these structures so clearly, though Abela’s dedication to her craft is equally indebted to a very English workmanship. As someone born in the generationally nebulous 1996, she shrugs off over-emphasizing any one label. She says growing up with social media “must be the big delineation” between Millennials and Gen Z, but observes that the way the two groups react to outside stressors offers another way to understand them.

“The Industry headline will be, “the first real Gen Z drama,” and I’m like, ‘What?’” she laughs. “Millennial, Gen Z… I think, in a way, that’s what the show is about: These cuspers who aren’t woke enough to call bullshit when they see it, and know what they can and can’t stand up to; but not Millennial enough to put up with it and endure the trauma. That’s where our drama sits, in the friction of those two worlds.”

Marisa Abela on Industry.

A “Zillennial” myself, I mention that I’ve yet to come across another character in our age group who, like Yasmin, displays her sexuality proudly and prominently without it being packaged for shock value. Throughout the series, Yasmin regularly indulges in casual sex after leaving an unsatisfying boyfriend, and the way her sexuality coexists with her professionalism becomes one of her character’s most fascinating arcs.

“Yasmin is very unsure of herself at work—unsure of how to navigate these relationships with people she might not otherwise have ever met in her life,” Abela says, mirroring her own outsider status with finance types. “Rather than having this constantly terrified, birdlike girl, there needed to be a real surety with her sexuality. I thought it would be really exciting to see this young woman not questioning whether anyone thought she was sad about the way she looked. How exciting, you know?”

She continues, speaking from a place of thoughtfulness and assuredness, and I’m reminded of other venerated English thespians who were completely self-assured from the jump, treating onscreen nudity as both an intellectual acting challenge and a completely natural form of expression: the Vanessa Redgraves, the Helen Mirrens of the world. (Quietly, I punish myself for setting up this dichotomy.)

“Women struggle with their sexuality and sensuality, and there are so many amazing television series and books that help us understand that but, what if, just once, with this character, that is not the issue?” she asks. “She loves her body, she loves having sex, she loves the way people are attracted to her. And that just turns her on, in every aspect of that phrase. I thought, as a sort of a provocation point, why don't we just go for that? If the question on the exam is, ‘Is Yasmin purely happy in her sexuality?’ Then yes. ‘Discuss?’ That’s what the show does.”

Still, Yasmin’s character struggles with other aspects of her life, particularly her troubled home life which, though well-bred and affluent, is on the constant verge of collapse. I ask about her character’s ease with languages, since the series almost borders on comedy every time she whips out a new, perfectly spoken tongue with a foreign client, or at her Persian home.

“Yasmin’s a chameleon, and that's where she feels comfortable: in trying to mirror the people around her,” Abela explains. “If that's a natural proclivity for you, languages make sense. She's entitled, but she's not entitled enough to have never learned another language, and that's where her insecurities come in. She just wants to make sure everyone around her is comfortable and that she's not putting anyone off. She’s well-bred in that way.”