Kenny Scharf’s Life in Parties

The artist known for his psychedelic, out-of-the-box interventions retraces his wild ride.

The first day Kenny Scharf visited New York, in 1977, he found himself at Food, the fabled artist-run SoHo restaurant, when a commotion outside alerted him to the fact that Faye Dunaway was running down the street in a split skirt, filming a scene for the fashion thriller Eyes of Laura Mars. “That was so much more Hollywood than anything I remember growing up,” says Scharf, who was raised in Los Angeles and attended Beverly Hills High School with the children of multiple stars. Less than a year later, he returned to Manhattan to study at the School of Visual Arts, drawn by the allure of Andy Warhol and the combination of art, music, and nightlife. “Me and every other kid who moved to New York at that time wanted to be part of that,” he says. Within his first week at SVA, he met Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Joey Arias. “The next thing I knew, I was onstage dancing as a go-go boy behind Klaus Nomi at Max’s Kansas City,” he recalls. By the time he graduated, in the early 1980s, Scharf had emerged as a core member of the DIY-driven East Village art scene, which was more concerned with taking over the streets than with infiltrating the insular gallery milieu. His go-to motifs—ecstatic blobs, strung-out rats, and cartoons appropriated from pop culture—soon adorned not just canvases but murals, merchandise, fashion collections, and the interiors of nightclubs. Eventually, Scharf won over the art world (he was represented by the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in the 1980s and included in the 1985 Whitney Biennial) and came to count Warhol as a friend. But his countercultural spirit endures: Today you’re just as likely to see Scharf’s work zipping by on the side of a car as you are in a museum.

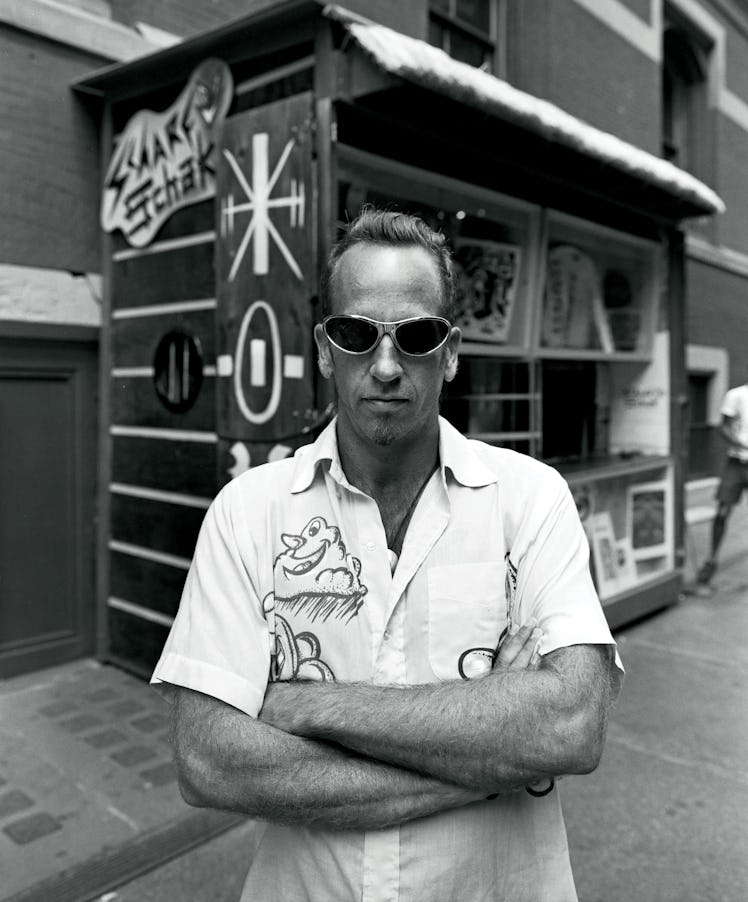

Scharf poses for his friend Wendy Wild, a musician and performance artist.

In the early 1980s, Scharf and his friends sourced most of their wardrobes from dumpsters. “We would find all these amazing 1950s clothes in the trash, like sharkskin suits and leopard housecoats,” he says. “We would cut them up and turn them into shirts.”

When Scharf visited the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro in 1985, he found the conditions lacking. “Back then, there was absolutely no money for art in Brazil. The museum had holes in the ceiling. I remember rain coming in,” says Scharf, seen below holding up a canvas featuring Rio’s Sugarloaf Mountain. “I painted that as a donation for them, and I did it there on the spot.”

When Studio 54 founders Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager opened Palladium, in 1985, they commissioned artists like Scharf, Haring, and Francesco Clemente to paint murals on the walls (above). For Scharf, the project was a natural outgrowth of ’80s East Village nightlife. “That was where we were coming from: Club 57, the Mudd Club, Danceteria—all those clubs were where the artists would go, not only to have fun but to meet each other,” he says. “There were artists making things and showing things in these spaces.”

Scharf poses in front of his work with friends Oliver Sanchez and Min Thometz-Sanchez, in Bahia, Brazil.

In 1983, Scharf married Tereza Gonçalves, a free-spirited woman he had met on a plane, and a few months later he absconded to her home country of Brazil. “I guess I was getting a little bit famous at the time, and I was a little confused at how people acted differently. Going there was like, Okay, these people don’t know anything about me.”

Scharf staged his first show at Fun Gallery, a punk space run by the underground actor Patti Astor. Along with Scharf and his pals Haring and Basquiat, Fun championed graffiti artists like Futura 2000 and Lady Pink. “The art world was pretty closed-door at the time,” Scharf says. “There was no communication between us kids and traditional galleries or museums. But the whole city was a riot of paintings on the subway and in the street.” Above: He and Haring collaborated on a mural at the Houston Bowery Wall in the 1980s.

A woman dancing on top of a car painted by Kenny Scharf

Scharf’s exhibition openings often incorporated elements of nightlife and performance art. Actor Ann Magnuson, who also ran the hot spot Club 57, appeared at a 1984 opening at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery, performing on top of a Cadillac that Scharf had customized. “There’s still a scratch down the back of the car from her heels,” he says.

In 1984, Scharf became a father. “I’m very spontaneous. I was even more then.” He says one day Gonçalves asked him if he wanted to have a child, and “then the next thing you know, you have a baby.” Though the family eventually relocated, his daughter Zena spent her first 17 months in his East Village apartment (above), every surface of which was covered with Scharf’s work. Their second daughter, Malia, was born in 1988.

Scharf and Haring pose with Warhol at the birthday party for fashion editor Elizabeth Saltzman in 1986.

Andy Warhol was an inspirational figure in the downtown scene. “He gave us so much, and we gave him admiration in return,” says Scharf. “There’s nothing like having a bunch of us whippersnappers running around you, worshipping you.”

In addition to his apartments, Scharf adorned his cars and clothing with his work. “What excites me about the artists I love is that they live their art. If your clothes are painted, and your car is painted, and your phone is painted, and your house is painted, it’s like you create your own world,” he says. “Then people can see it, so they can be invited in as well.”

Scharf thinks that when the chemistry is right, fashion and art can be great bedfellows. In 1992, he collaborated with the clothing brand Bohemian on a collection of men’s dress shirts. “To have someone see something at a museum—fantastic; it’s such a high level. But then to have someone just parking their car and see it walk by, it’s also impactful, in different ways,” he says.

Scharf and Gonçalves at an opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1991.

Scharf still isn’t sure that he has fully gained entrance into the art world’s upper echelon. “I’m doing well and having shows, but when I think of the establishment, I think more about museums,” he says. “You can never try to get them to accept you. That doesn’t work. So I just keep doing what I do, and then, hopefully, if I’m not ancient or dead, I’ll get that acceptance. In the meantime, I’m enjoying myself, so that’s good.”

In the 1990s, Scharf created a custom room at Peter Gatien’s Chelsea nightclub, Tunnel, called the Cosmic Cavern.

“I wasn’t partying anymore; the people who were would come up to me and say, ‘Oh my god, your room at the Tunnel. How high was I?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, I’m glad I could help.’ ”

The HIV/AIDS epidemic had a profound effect on Scharf’s social circle and his youth. “What happened was, you know, party, fun, dance. And then, all of a sudden, everything was funerals in the day and parties at night to raise money for hospitals, doctors, everything. A lot of these kids, their families abandoned them,” he recalls. In 1989, he appeared alongside Jean Paul Gaultier and Lauren Hutton as a judge for the showcase at Susanne Bartsch’s legendary fundraiser, the Love Ball.

“I came out of that whole world of performance and installation,” says Scharf. “So I was able to create the Cosmic Caverns out of garbage—plastic, mostly—painted fluorescent, and make this whole world of a psychedelic womb.” Here, Scharf wears a jumpsuit customized by Stephen Sprouse in front of his installation at Palladium in 1985.

Scharf collaborated with fashion designer Todd Oldham on a print for Oldham’s spring 1994 collection (a version of which Fran Drescher would go on to wear on The Nanny).

However, his most fruitful fashion partnership has been with Dior Men’s artistic director Kim Jones, who incorporated Scharf’s work into the entire pre-fall 2021 collection. “It was amazing, because usually I want everything changed,” says Scharf. But he saw Jones’s work and said, “Perfect. Fantastic. Looks great.” Above: A look from the collection.

Like John Baldessari (above, with Scharf at the 2016 MOCA Gala in Los Angeles), Scharf sees himself as a California artist despite his career origins in New York. “I’ve lived in L.A. since 1999. I grew up here,” he says. “Yet to this day, people will say, ‘Oh, so how’s New York?’ ”

In 2002, in the early days of Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim, Scharf created a pilot for an animated show called The Groovenians. Appropriated characters from The Jetsons had long shown up in his work, and this was his own attempt at cartoon futurism, featuring a voice cast of Paul Reubens, Dennis Hopper, and RuPaul. Above: Scharf and his daughter Malia pose with Lenny Kravitz and his daughter, Zoë, at a party celebrating the premiere.

Scharf and his family moved to Newburgh, in upstate New York, in 1987. “We lived there and I painted there, and nobody came,” he says. “We thought people were going to visit all the time, but nobody did. I mean, some people did, but it wasn’t the Hamptons, let’s say.”

Scharf found himself temporarily back in New York in the aughts, this time in Brooklyn. His basement had collected fragments of Cosmic Caverns past, and the stock market was crashing—with the art market right behind it—so he started throwing parties with a $5 cover fee to help pay the rent. “It was highly illegal, could not have been done in Manhattan,” he says. “But in Brooklyn, no one seemed to care.”

This article was originally published on