The Private Provocations of Karl Lagerfeld

In an exclusive excerpt from his book Paradise Now, author William Middleton, a former W editor, recalls his adventures with Lagerfeld—and sheds light on the designer’s famous falling-out with Yves Saint Laurent.

It was January 1995 that I first met Karl Lagerfeld. He would be turning 62 that year; I was 33. At that point, I was the newly named Paris bureau chief for Fairchild Publications, overseeing Women’s Wear Daily and W magazine, which had been, for decades, two of the most formidable and feared fashion publications in the world. The group was run by John Fairchild, always referred to as Mr. Fairchild, who had turned a sleepy, family-run firm into a media powerhouse. One of my responsibilities was going to the major houses to do a preview of the 1995 spring/summer haute couture collections that would be presented later that month.

It was only a few minutes’ walk from our offices at 9 Rue Royale to the famous headquarters of Chanel at 31 Rue Cambon. Once past a security guard who placed a call upstairs—the house was so much smaller in those years, simpler—our photographer and I took a tiny elevator up to the top floor. The door to the atelier was beige with black block letters spelling out the word “Mademoiselle,” the preferred title of the founder, and, below, only one word, a warning, really, “Privé.” The door led directly into the large room with a wall of windows on the far side and floor-to-ceiling mirrors on each end. It was a matter of days before the couture collections, and the Chanel studio was buzzing. Karl was sitting at his semicircular, oversize desk, his back to the windows, wearing a black suit by Yohji Yamamoto. “I wear only black jackets, black pants, black ties, and white shirts,” he explained in those years. He had just started, however, powdering his hair white. Karl was a master at media relations, so, of course, he was charming from the moment we were introduced. He lowered his sunglasses, offered a warm smile, and the brisk handshake favored by the French, one pump, up and down. Karl had that skill, incredibly rare, of being able to concentrate completely on the act of greeting someone, blocking out everything else that was around.

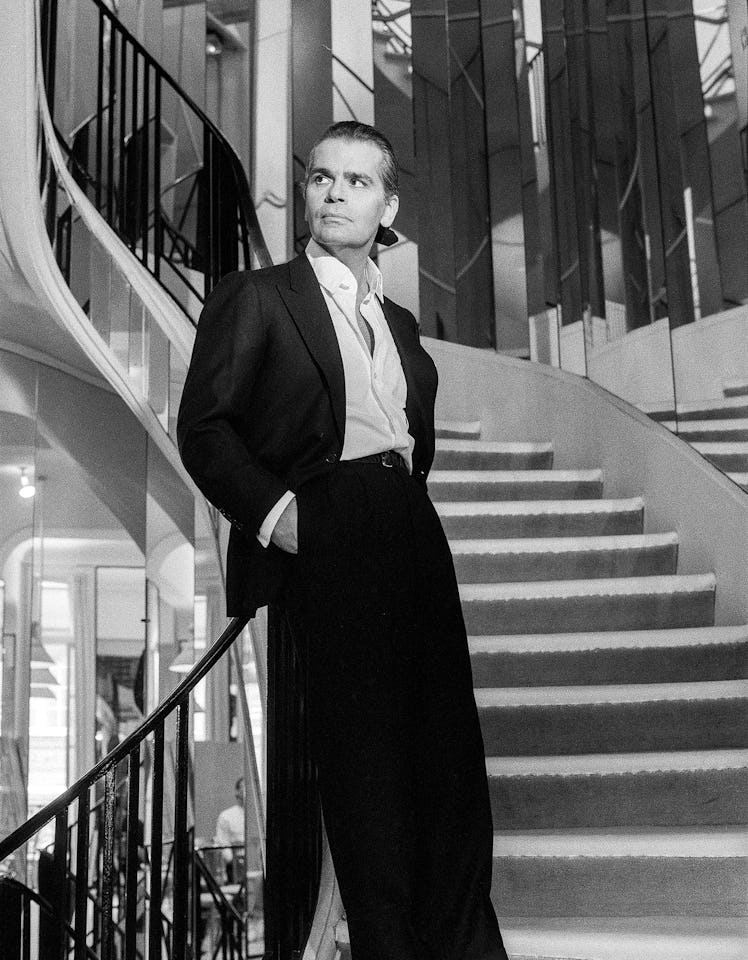

Karl Lagerfeld at his home on the Place Saint-Sulpice in Paris, November 1976.

The room was filled with more than a dozen members of the Chanel team and those brought in for the preview: the directors of the couture ateliers, seamstresses, models, hair and makeup stylists. Introductions were made to the team. His assistant was Gilles Dufour, the designer who had been a friend of Karl’s since the 1970s; tan, also wearing sunglasses, in an impeccable dark suit with a tie and pocket scarf. Victoire de Castellane, Dufour’s niece, responsible for Chanel jewelry, had a sparkling personality and an irreverent style—including fetish gear that she picked up at sex shops in Pigalle—that was a great inspiration for Karl. There was music playing, and the mood in the room was lively and much friendlier than might be expected—the studio did not feel like an ivory tower or a super serious laboratory of haute couture. There was some tension in the air, of course—it was the first time the new collection had been shown—but everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves. At the same time, there was a brisk efficiency about it all. And Karl, at 61 years old, was very much running the show.

A model walked out from behind a screen in the corner of the room, wearing one of those perfect Chanel suits. This one was black wool, with a nipped waist, strong shoulders, and skirt length just above the knee. Karl opened the sketch pad that was always on the top of his desk and drew a quick outline of the silhouette. With just a few strokes, he was able to convey the newest line. He tore off the page and gave it to me. That season, he explained, would be practically all black. “It is not black in the sense of black,” he explained. “It’s black in the sense of chic!”

The earliest known drawing by Lagerfeld—from 1942, the year he turned 9—shows him taking a nap in his room, his bedside table crowded with books.

The designer at 4 years old, in 1937.

It was an absurd comment, of course. It meant nothing. And, yet, it said everything. And Karl’s line flowed right onto the front page of Women’s Wear Daily. “ ‘It’s not black in the sense of black—it’s black in the sense of chic,’ says Karl Lagerfeld of the spring Chanel couture collection he will unveil Jan. 24,” read the cover. “That may be the leading shade at Chanel but Karl’s hair has gone positively white. ‘I’ve taken to powdering it,’ he admits. It’s all the better to get into his retro mood, with a new silhouette that features a longer corset, squared shoulders and a raised waist.” The newspaper headline was “Taking a Powder,” suggesting that, by that point, information about Karl’s life could be as newsworthy as the fashion.

It was the first of many occasions we had to work together. For several years, just before the couture and the ready-to-wear shows, I was the first to talk with him about what he was going to present—at Chanel, at Chloé, and at Lagerfeld—and then to explain it to the world. The first magazine story we did together, in July 1995, which he photographed, was his just-renovated apartment in Monaco (the title: “Monte Karl”). He had filled the interiors with the best neoclassical designs from the French 1940s, including lacquered daybeds by André Arbus, forged iron and marble tables by Gilbert Poillerat, a corner canapé, in a dusty rose, by Christian Bérard for Jean-Michel Frank. “I’m a frustrated interior designer,” Karl said about his work on the apartment. “It’s fun to play with different styles, different periods, different atmospheres. It’s a very luxurious, very expensive way to play, but it’s fun, non?”

Lagerfeld presenting his debut couture collection for Jean Patou, July 1958.

In the spring of 1996, I flew with him in his Falcon 50 jet to Hamburg to do a story on a neoclassical house he had bought, like a modernist Greek temple, in the same neighborhood where he had been born. Karl photographed that story, as well. For the trip to Hamburg, we were to meet at the private airport of Le Bourget, north of Paris. I joined a group waiting for him: members of his teams at Chanel and Lagerfeld, his financial manager, his antiques consultant, and his picture framer—his team of movers, who shuffled between his various properties, was already in Hamburg at the house. Karl was notoriously tardy, so we waited. And waited. “It’s not that Karl is ever late,” quipped one member of his team. “Whenever he arrives is the right time. It’s the rest of us who are early.”

Of course, our relationship was also mutually beneficial. I represented two publications that were extremely important in his world, so it was in his interest to cultivate me. And he was the leading figure in the Paris that I covered, so it was essential that I establish a rapport with him. Nevertheless, quite quickly, Karl and I began to have a good working relationship, even a friendship. He had handwritten notes messengered over to the office, in thanks for a story or a review, with comments on the latest fashion news, or with his most recent photographs of beautiful young men. The cards were extravagant, with designs drawn by Karl and, I later learned, printed in Germany by Steidl. They arrived in large portfolio envelopes, with an oversize card inside and matching paper. He also sent extravagant bouquets of flowers from Lachaume, still his favorite florist, with a thoughtful, handwritten note. It was usually clear when a bouquet from Karl arrived—the lavishness of the arrangement gave it away from across the office.

With sketches of Chanel’s fall/winter haute couture collection, March 1984.

I was not, in any way, one of Karl’s best friends. But I respected him, as a designer, of course, particularly for what he had accomplished at Chanel, but also as someone who was fully committed to the culture of his time. He knew everything that was going on in the worlds of art, cinema, music, photography, and design. And he had a firm grasp of history. He was also eager to share his knowledge, but, at least with a journalist, in a gentle way.

In September 1996, I worked with English photographer Miles Aldridge to do a series of previews of the upcoming ready-to-wear collections for W. We photographed Vivienne Westwood at work at her atelier in London, John Galliano in a café across from his apartment, and Gianfranco Ferré with a model sitting on his desk at Dior. Yves Saint Laurent was captured alone in his private office on the Avenue Marceau. He was wearing a dark pinstripe suit and his signature tortoiseshell glasses, and was looking directly at the camera. To explain the season, Saint Laurent sighed and told me, “I’ve seen so many dresses in my life.” He seemed to be exhausted by it all.

Outside the headquarters of the couturier Pierre Balmain, who had hired Lagerfeld as an assistant on the night of the young designer’s victory in the Woolmark Prize competition in 1954.

Posing for a portrait with model Kristen McMenamy at the Chanel studio, January 1993.

For Karl, we photographed him in the courtyard of Chanel on the Rue Cambon, in the back seat of his Volvo, with the model of the moment, Kristen McMenamy. He was wearing a black corduroy suit by Yohji Yamamoto, a dress shirt, a dark tie, and sunglasses, while McMenamy was modeling next season’s velvet dress for Chanel in vivid lavender. Of course, Karl came up with a sharp quote: “I should walk, but, on the streets, people always ask me for jobs.”

During the shoot, it was clear that Miles, an attractive young man from London, was taken with Kristen. Who wouldn’t be: She was one of the most beautiful models in the world, with an electric personality. After we got the picture, she said goodbye to the team and started walking back into Chanel. I told Miles that he should go in and invite her to come to our last photo that day, which was happening at Anahi, a South American restaurant near the Marais that was a fashion canteen. He did. She came to the restaurant. We shot a lovely portrait of the designer Martine Sitbon and her art director husband, Marc Ascoli, before all having dinner together.

That night, Miles and Kristen began a romance. She often said that they were a couple who began in the back seat of Karl’s car. It was a racy-sounding comment that delighted the designer.

With his companion Jacques de Bascher in Paris, 1979.

Giving away McMenamy at her wedding to photographer Miles Aldridge in London, October 1997.

A year later, at a ceremony in London, Aldridge and McMenamy were married. Six months pregnant by that point, she wore a gorgeous, Empire-waist gown in peach chiffon designed by Karl for Chanel. He also made the trip to London, to walk her down the aisle. “It’s not easy being the father of the bride,” Karl said to me that day.

I began to spend enough time with him that I had a good sense of how he was when he was offstage. His public image, particularly at that time, was harsh: the somber suits, the oversize fans, the dark glasses, the bitchy bons mots. But that was not the person I saw behind the scenes, and I was struck by the difference. One day, having lunch at his apartment on the Rue de l’Université, I raised the subject. I told him that I had never seen anyone who had a public persona that could be so harsh, intimidating, even unpleasant, but that once you got to know him, you discovered that he could actually be quite warm, even touching. He shot back: “Better that than the opposite, non?”

Karl loved to provoke. For the press, it was a role he played, meant to ensure that he was never far from the spotlight. And it worked: His constant presence in the press, his sheer quotability, helped fuel his reputation. In private, his provocations were different. They were warmer, less mean-spirited, tending to involve a little gossip, a clever turn of phrase, or were just to have a laugh. They could still, however, pack a punch.

Lagerfeld (center) in his apartment at 35 Rue de l’Université, with model Pat Cleveland and fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez, circa 1969.

For many years, Karl and Saint Laurent had been the best of friends. Yet by the time I knew them, they had not been close for years. A rupture had taken place in the 1970s, when Saint Laurent pursued, and then slept with, Jacques de Bascher, a seductive aristocrat who was the great love of Karl’s life. Their affair did not make Karl jealous. His relationship with de Bascher was an emotional and sentimental one, a passionate friendship, rather than something sexual. But Pierre Bergé, the business partner and longtime lover of Saint Laurent, felt that de Bascher was a threat to his relationship and to the house that they had built. So, Bergé forced a falling-out: between Saint Laurent and de Bascher and between the two designers. It created something of a schism: Two of the biggest names in Paris fashion were estranged, and most felt the need to choose one side or the other. There were exceptions, but for many years, you were on either Team Lagerfeld or Team Saint Laurent.

By the mid-’90s, the great fashion triumphs of Saint Laurent were behind him. The house was successful—perfect, really, in many ways—but it existed mostly on inertia and the sales of fragrances and cosmetics. One day, we were doing an haute couture preview for WWD on the streets, near the YSL offices on the Avenue Marceau. The model was wearing thigh-high Saint Laurent boots in crocodile and an incredibly formal checked suit. It was very elegant but overwrought. Tom Ford, who was in the midst of his rejuvenation of Gucci, the most successful repositioning of a historic house since Karl had done the same at Chanel, happened to drive by our shoot. A few nights later, I met Ford and his partner, Richard Buckley, for dinner, and he raised the subject. “I saw your Saint Laurent preview,” he said, with an arched eyebrow. “I wouldn’t say that it looked particularly modern!”

Lagerfeld’s sketch of de Bascher, 1975.

A note card to the author with a drawing by the designer.

Saint Laurent was barely 60 by that time, but his years of alcoholism and drug abuse had caught up with him. He appeared much older than his age, moving slowly and speaking hesitatingly. His image was propped up by a circle of enablers of his various addictions, by sycophants who treated his every move as an act of genius, and especially by the pugnacious Bergé, who controlled every aspect of the designer’s public persona and shot down any inquiry that might have come too close to the truth. Bergé’s combativeness allowed Saint Laurent to play the suffering genius. And play it he did.

Karl, in those years, was fully engaged and, when it came to his former friend, ready to stir things up. One afternoon, in his apartment on the Rue de l’Université, Karl was holding court around a massive round dining table in blond wood. Designed by Andrée Putman, it was his version of Frederick II’s round table at Sans Souci, the painting he had owned since childhood, which was hanging in his bedroom. Karl reached across the table, his own tafelrunde, and gave me a glossy print of an old black and white photo.

Taken in the ’50s, it showed him at the beach in Deauville, at the height of his bodybuilding phase, with the model Victoire Doutreleau, who had been hired personally by Christian Dior and was considered by many to be one of the first supermodels. I later learned that the photo was taken in the summer of 1956, meaning Karl was 23 years old at the time and working at Pierre Balmain. He was standing on the right of the frame in profile, wearing a skimpy dark swimsuit. Victoire, who was also 23, was in the center, wearing a polka dot bikini, her hands behind her back, smiling, with her eyes fixed on the camera. The beach extended all around them, and behind were the half-timbered buildings of Normandy. It was a striking image, one that I had never seen. When I told Karl how much I liked it, he suggested I go into the next room to see the original on the computer.

The photo had been taken on a weekend getaway to Deauville with Karl, Victoire, Yves Saint Laurent, and Anne-Marie Muñoz, who managed the studio for Saint Laurent throughout their long careers. In the ’50s, ’60s, and into the ’70s, the four were the best of friends. They went to the same restaurants, the same clubs, were members of the same social set. In 1963, when Muñoz had her son, Carlos, she asked Karl to be the godfather.

Lagerfeld at the beach in Deauville, France, in the summer of 1956, with model Victoire Doutreleau. Missing from the photo is a young Yves Saint Laurent, who was sitting on the sand to the left before Lagerfeld had him erased from the image

After he handed me the photo from Deauville, I went into the next room in Karl’s apartment, a massive salon that had been converted into a photography studio. The floors were wood parquet, while the ceiling, very high, was covered with ornate swirls of white plaster moldings. I relayed what Karl had said to his assistant. Working on one of those unwieldy computers of the time, he located the scan of the old photo. It turned out that there had been one major alteration to the lovely scene in Deauville. Karl had asked that it be retouched. In those days, Photoshop was far from ubiquitous, so reworking the photo required effort.

On that sunny day at the coast, there had actually been three people in the frame. In the original, just to the left of Victoire, sitting on the beach, was Saint Laurent. On the print that Karl had given me, where Saint Laurent had been, was nothing but a mound of sand.

Excerpted from Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld, by William Middleton. © 2023 by William Middleton, published by Harper on February 28, 2023.