In Montreal, a New Exhibition Spotlights Basquiat’s Devotion to Music

Jean-Michel Basquiat, one of the most captivating artists of his generation, has been the subject of countless exhibitions delving into his triumphant (albeit fugacious) career. But a new show now on view at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts sheds light on a crucial and mostly unexplored facet of this trailblazing American artist: his devotion to music.

A collaboration between the Philharmonie de Paris and the MMFA, “Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music,” open until February 19, 2023, is the first expansive exhibition dedicated to surveying the importance of music in the life and career of Basquiat.

The show features more than 100 pieces, including archival documents, film footage, notebooks, and artworks. In addition to exploring the melodies that inspired his artistic output during the ’70s and ’80s, the show illuminates how Basquiat turned to music as a means to call out racism and inequality, while also honoring his relationship with a wide array of performers, such as Charlie Parker and Max Roach, and, most notably, his career as a musician with the band Gray—of which he was a co-founder.

“[Basquiat’s] friends and collaborators say there was never a moment in his studio when music was not on. He owned 3000 records, and there’s never been an exhibition that has looked deeply at how music was much more than a soundtrack to his life. In many ways, it structured his practice,” says Mary-Dailey Desmarais, chief curator at the MMFA and co-curator of the exhibition with Dieter Buchhart, guest curator, and Vincent Bessières, guest curator of the Philharmonie de Paris.

Moreover, “Seeing Loud” spotlights Basquiat’s unique ability to experiment with music and painting techniques. “He embraced a spirit of DIY experimentation and invented instruments. A convergence of hip hop and visual arts, poetry, and literature in interesting ways—the backdrop against which he made his paintings,” Desmarais adds.

Below, a selection of some pieces included in the exhibition, with fascinating reflections by Desmarais regarding their significance.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), King Zulu, 1986. MACBA Collection, Barcelona, Government of Catalonia long-term loan (formerly Salvador Riera Collection). © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

“King Zulu is an essential painting that lays bare how music was for Basquiat a means of engagement with diasporic histories,” Desmarais says. “In this painting, he refers to a key event in the history of jazz and blues: an episode in the life of Louis Armstrong, who, in 1949, was named King of the Zulus during the Mardi Gras Festival in New Orleans. It’s a painting that shows the depth and complexity of Basquiat’s knowledge of jazz.”

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), Kokosolo, 1983. Rechulski Collection, New York. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

The title of this painting, Kokosolo, is a direct reference to a famous jazz composition by musician Charlie Parker. “In this work, [Basquiat] has photocopied many of his own works and made a composition that evokes—in its arrangement—the ways jazz musicians compose their solos,” Desmarais explains.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), Now’s the Time, 1985. Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

“Now’s the Time is an enormous disc Basquiat made in homage to Charlie Parker's record of the same title," says. “Basquiat saw Parker as a kindred spirit and a staggering genius who was a pioneer of bebop. The phrase ‘now’s the time,’ reads like a kind of decree and almost call to action—not just to recognize the importance of jazz and bebop, but to seize the day.”

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) et Andy Warhol (1928-1987), Arm and Hammer II, 1985, acrylique sur toile, 167 x 285 cm. Männedorf-Zurich, collection Bischofberger. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. © 2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN

Explaining the significance of this collaboration between Basquiat and Warhol, Desmarais says, “In his intervention of the canvas, Basquiat places an image of Charlie Parker with the date of his death on the bottom, almost as if to make a logo, but also as a sort of commemorative coin. In doing so, he brings in so many other issues, notably issues of race, commodification of celebrity, and how musicians like Parker were beholden to record industries and often underpaid.”

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), Beat Bop, 1983. Collection of Emmanuelle and Jérôme de Noirmont. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Beat Bop is a reference to a song of the same title by American artists Rammellzee and K-Rob, which was produced by Basquiat. According to Desmarais, “Basquiat was profoundly aware of the fact that African American contributions to American culture were underrecognized; so many of his paintings celebrate Black artistry.”

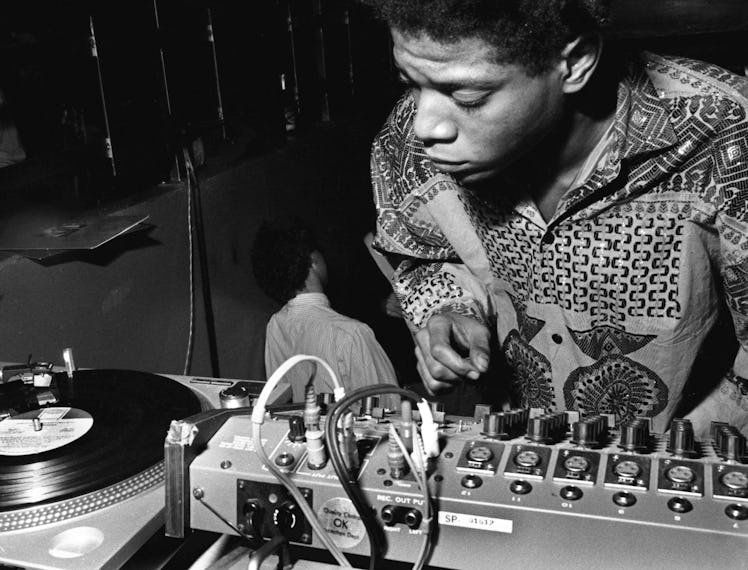

The band Gray performing at Hurrah, 1979. Photo Nicholas Taylor. © Nicholas Taylor

An entire section of "Seeing Loud," looks into Basquiat's participation in the band Gray, which he co-founded in 1979. The band was named after the renowned medical book "Gray's Anatomy," which was gifted to the American singer by his mother when he was a child and went on to inspire many of his creations.

“3x3,” with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Danny Rosen, and Wayne Clifford, directed by Ed Steinberg, 1980. Production by Rockamerica/Rockamedia.

This never-before-seen archival film is one of many on show at the MMFA exhibition. Here, Basquiat is pictured with fellow Gray bandmate Wayne Clifford and his close friend, Danny Rosen, a regular of the riveting New York club scene.

View of the exhibition Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music. Photo MMFA, Denis Farley. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Speaking about the series of Basquiat’s notebooks included in the exhibition, Desmarais says, “we wanted to show how he understood the musicality of language. He was a poet, and this is something that's not always discussed in his work, but he had a profound understanding of the sound and shape of words and how they echo against one another."

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), Untitled (Sheriff), 1981. Collection of Carl Hirschmann. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

“This painting is quite fascinating because it's a work that hung behind the bar for quite a long time at Club 57, one of Basquiat’s favorite musical scenes. So, on one level, it speaks to this confluence of music and art at the time, but it’s also a painting that shows an episode of violence between a sheriff and what looks like a prison inmate. There are these letters ‘O, A, O, A’ which conjure the sounds of a body getting beaten, and he's using them almost like musical notes,” Desmarais says.