Janette Beckman Photographs Punks, Hip-Hop Legends—and Maria Grazia Chiuri

Welcome to Ways of Seeing, an interview series that highlights outstanding talent in photography and film—the people behind the camera whose work you should be watching. In this week’s edition, senior content editor Michael Beckert chats with the renowned documentary photographer Janette Beckman, whose latest project involves New York City radio DJ Megan Ryte.

How did you first get into photography?

I always knew I wanted to be an artist of some sort. I was always drawing as a kid or in the art room at school. I ended up going to art school and I wanted to draw like David Hockney, who was the trendy artist at the time, but I honestly didn’t think I was good enough. I ended up switching to photography and when I graduated, I started teaching at a college. It was a time in England when everything was sort of awful really. The economy had crashed and nobody had money, but it was free to go to college in the UK. Punk was starting to happen all around, and I started photographing kids on the street. One day I walked into a music paper called Sounds with my portfolio—which, actually, didn’t have any music pictures in it at all—and the editor was like, “What are you doing tonight, do you want to go photograph Siouxsie and the Banshees?” I didn’t really know what I was doing, but I said yes and the rest is history. I started shooting for all the music papers, and eventually The Face magazine.

When did you decide to move from your hometown in London to New York City?

Around 1982, the first hip-hop show came to Europe; we’d never seen anything like that before. I was photographing the show that night for a publication, and I started photographing all the people there—they looked really different to me. Punks didn’t really look like that, it was a whole different style of music, but also a different style of fashion. It was a renaissance moment for me. Months later, I went to visit a friend in New York, and I never went back to London.

So New York drew you in immediately.

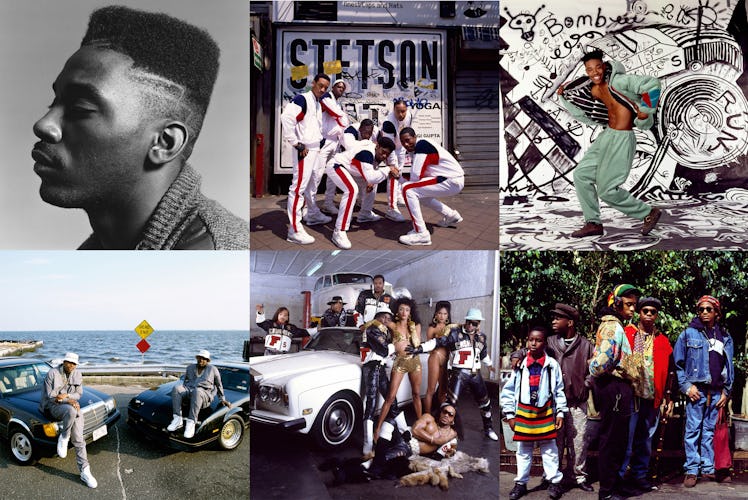

That’s exactly what happened. My friends lived in Tribeca—of course, it wasn’t the Tribeca that is there today. It was so great; you’d walk out onto the street, the subways were covered in graffiti, kids were breakdancing, you could buy a fake Gucci handbag for $5.00. I ended up moving to the East Village in the eighties. The energy in New York was just so much more vibrant than London’s, especially at that time—it was so different than the punk scene. Everyone here in New York seemed more upbeat and optimistic. Everyone had style and attitude, they were rocking the latest Puma sneakers. The Face magazine knew I was here, so they’d call me up and ask me to photograph a new group. Back then, they’d just give you a phone number and you’d call them up and agree to meet down by Hollis station in Queens to take pictures. Years later, these photographs are a real part of history, but back then, we didn’t even know hip-hop was going to end up being the biggest music genre in the world.

LL Cool J, New York City, 1985. Photograph by Janette Beckman.

There were a lot of similarities between punk and hip-hop. Rappers and punks both came from poor economies, from kids whose voices hadn’t been heard before. You listen to the Sex Pistols singing “No Future,” and then you listen to “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash, and you see the similarities. They’re describing what their lives are like.

Queen Latifah, New York City, 1990. Photograph by Janette Beckman.

In an American Photo Magazine article, you said many of the people you photographed early in your career weren’t legends yet. Do you prefer working with people before or after they’ve been so heavily documented?

I did the first Police album cover, and I’m working on a book about the band that’s supposed to come out this year. I got this great quote from Sting—he said “We were just three guys standing in a tunnel. None of us knew that this photograph would become so iconic.” We were all figuring out the shot together. When you’re photographing someone that is already a legend, it’s a whole other situation: you’ve got the manager, the hair, makeup artist, stylist. I’ve done a lot of shoots for Interview magazine, where we’ll take an artist like BANKS, and we’ll turn her into a superhero. She’ll arrive to set in regular clothes, and we’ll throw her in this tight latex look and high heel shoes, and suddenly she’s a totally different person. There are some legends I’d love to photograph, but there’s something so great about just taking someone off the street and photographing them as they are.

You’ve shot some incredible ads for Dior, Levi’s, and the cast of Pose. What has it been like to translate your practice, which originated in documentary photography, into a more commercial space?

Those shoots have come to me in the last few years. The creative director of Levi’s, for example, is a huge music fan, and I guess he loved my pictures of hip-hop artists. The Levi’s shoot was a three-day shoot in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, and in Jersey City, New Jersey. We had a DJ on the street, and our casting director would street cast right from the neighborhood. For Dior, I was shooting in Detroit when I got a call from their creative directors saying they wanted me to come to Paris to shoot their campaign. That was Maria Grazia Chiuri’s first collection, and she was a big fan of punk—she had my Made in the UK book. I went there, and we had a meeting. She was like, “What would you like to shoot, Janette?” I told her, “What if I document you making the collection?”

Tell me about this new collaboration with DJ Megan Ryte of Hot 97, the New York City hip-hop and R&B radio station? It was a great commission, and it came during Covid, of course.

We had to make sure everything was Covid safe. Working with Megan was pretty amazing—we had an immediate connection the second we met. There was definitely this shared female power between us. Every photography project, for me, is a collaboration, and when you’re working with a subject, you need to make them feel comfortable, so that was my top priority. I think because I was a woman, she felt okay to be who she was. We wanted her to have attitude, and look powerful. She was wearing sneakers, but she looked so fierce, and her nails were incredible. This project was the first one I had done where the creative director was remote over Zoom, so that was strange, but it worked out so well.

DJ Megan Ryte of Hot 97 photographed by Janette Beckman, in collaboration with Platoon.

What are you most proud of in your career so far?

I’m so proud that I’ve been able to witness and document so many of the amazing people I’ve met throughout the years. From photographing the Harlem bike club the Go Hard Boyz, to working with Levi’s, people have allowed me into their communities to make this work, and I’m so grateful. I should mention that growing up, I was sort of horribly shy as a kid, and then I suddenly realized at a certain point, if you pick up a camera, it gives you an entryway into someone else’s life. It allows you to go up to someone on the street and ask to take their portrait. It changed my life.

Collaboration between Janette and DJ Megan Ryte was commissioned by Platoon. Stream Megan’s new album here.

This article was originally published on