A Look Back at JAM, the Boundary-Pushing Art Gallery Still Unlike Any Other

Just Above Midtown’s seemingly impossible 12-year run gave Black artists an unprecedented commercial platform—and drove its founder, Linda Goode Bryant, deep into debt.

To say that Linda Goode Bryant did her utmost to keep the lights on at Just Above Midtown, the groundbreaking gallery she founded in 1974 as a rebuke of the gatekeeping New York art world, would be an understatement. Look no further than the 350 or so facsimiles of bills, debt reminders, and eviction notices currently papering a wall of the Museum of Modern Art, home to an exhibition exploring the enormous impact and legacy of its 12-year run, on view through February 2023. “I can’t remember how Citi Bank left my life,” Bryant recalls, noting that she never did end up clearing her debts. “I think they said, ‘Oh, fuck this shit—we’re out.’” It wasn’t that she was trying to get out of making payments, but that doing so simply wasn’t possible. JAM was a laboratory for artistic experimentation, and Bryant, who was a 25-year-old single mother of two when she started JAM, was beyond committed. If, say, David Hammons wanted to show greasy paper bags of barbeque chicken instead of the body prints she’d already excitedly told debt collectors she’d presold (meaning she would be losing out on a desperately needed moneymaker), then so be it.

JAM shuttered in 1986, and there’s been nothing like it since—hence why art world figures like Thelma Golden, director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem, have been chasing Bryant to reverse her “I don’t do dead art shows” stance for nearly a decade. But when she realized she could think of it instead as a challenge to see whether JAM could be JAM at MoMA, where the curators assured her they were open to including current works from the artists featured, Bryant changed course.

The venue for “Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces” is of particular significance: The first of JAM’s three outposts was just a few blocks north of MoMA, and the location was meant to be a provocation of the institution and its storied—and overwhelmingly white—neighbors. “The art world was really hostile when JAM opened,” Bryant recalls. “I was reminded, daily, that we didn’t belong there by several galleries in the building.”

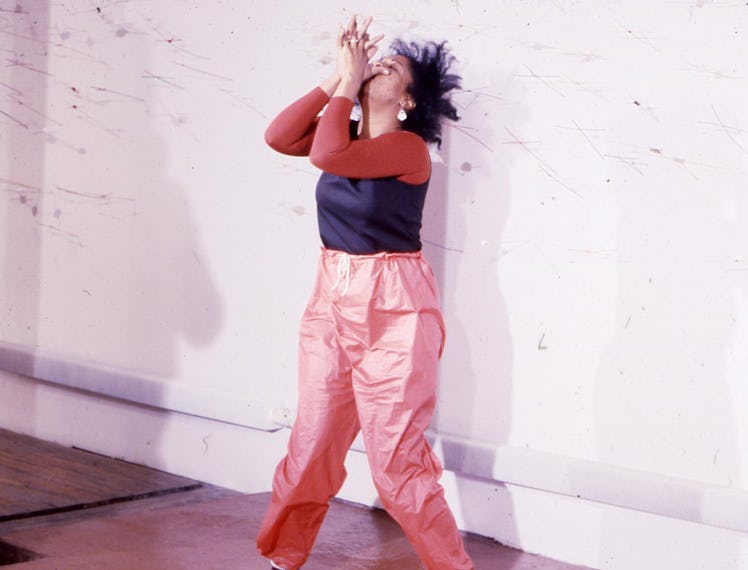

Linda Goode Bryant and Janet Olivia Henry (obscured) at Just Above Midtown, Fifty-Seventh Street, December 1974.

It’s no surprise, then, that JAM’s first opening made waves. “Black folks on 57th Street—that wasn’t happening back in 1974,” Bryant says. “So it was a big deal for artists in all fields, whether theater actors, filmmakers, dancers, or musicians.” As if JAM’s entrée onto the scene weren’t mold-breaking enough, Bryant had also decided to start things off with a hybrid of figurative and abstract works titled “Synthesis.” At the time, many in the community felt that to qualify as “a Black artist,” one’s work had to be figurative, not abstract or conceptual. Bryant wanted to take that on—and she wanted to show artists from California while she was at it. New York artists weren’t pleased—“724 square feet isn’t enough real estate for us, and you’re going to bring them in?,” pretty much sums up the response, she recalls. But Bryant stuck to her guns, convinced New York artists could use a look at work that pushed beyond Western abstraction and expanded notions of what could be considered art materials.

Barbara Mitchell (center right) and Tyrone Mitchell (far right) at the opening of the exhibition “Synthesis,” November 18, 1974.

“Synthesis” was JAM’s first show, but the aforementioned Hammons exhibition is the most related to the gallery’s genesis. Bryant had been encouraging the Black artists in her New York City circle, including those she encountered through her job at the Studio Museum, to take the lack of commercial opportunities into their own hands for some time. The idea to do so herself had been germinating when she approached Hammons at an arts conference in Chicago. They got to talking, and eventually, Bryant discovered she wouldn’t be seeing his work in New York any time soon: “I don’t show in white galleries,” he told her simply. Her initial disappointment soon gave way to excitement: “I said, ‘Well, I guess I’m gonna have to start a gallery.’”

By the time Bryant eventually showed Hammons, in a 1975 exhibition titled “Greasy Bags and Barbeque Bones,” it was clear she had started much more than that. Reactions such as “oh hell no” and “what the fuck is this motherfucker showing?” rose to a resounding chorus, and Hammons—to add insult to injury, yet another artist from the West Coast—wanted to let the artwork speak for itself. “I just asked everybody to sit down and talk,” Bryant recalls. “Everyone was saying, ‘What is this shit? How are you gonna make art without art supplies? Why?’ And at some point, an artist got out of the shock and anger and said, ‘Well, why not?’ And that was the last time I ever heard the debate about how you’re not a Black artist if you’re not a Black artist working figuratively.”

David Hammons (left) and Suzette Wright (center) at the Body Print-In held in conjunction with Hammons’s exhibition “Greasy Bags and Barbeque Bones,” Philip Yenawine’s home, 1975.

David Hammons, Untitled, 1976.

It’s no wonder why Bryant first billed JAM as a “forum”; such controversies and ensuing debates were commonplace. Which brings us to another controversy: the fact that she specifically billed it as “a forum that presented Afro-American artists on the same platform with other established artists,” meaning that not all of the artworks on display were made by artists who were Black. “I mean, the whole thing about just showing Black artists is that that would have been replicating what was happening in the art world,” she says. Her approach, which has been described as desegregationist, also served to highlight lesser-known non-white artists; a notable 1976 group show titled “Statements Known and Statements New” found Jorge Luis Rodriguez and Raymond Saunders on display alongside Jasper Johns.

Still from video footage in the JAM Records featuring Randy Williams, Marquita Pool-Eckert, and David Hammons with Jorge Luis Rodriguez’s Circulo con cuatro esquinas (Circle with Four Corners) (1976), in Rodriguez’s exhibition “Circulos,” Just Above Midtown, Fifty-Seventh Street, 1976.

Alas, breaking barriers meant breaking the bank. For JAM employees, lunchtime called for cheap buttered rolls; as for dinner, it started out with everyone pooling whatever they had in their pockets onto the table to make sure no one went to bed hungry. (Especially her two kids, whom the gallery’s artists helped care for by picking them up from daycare when Bryant was too tied up with JAM.) Bryant and what she refers to as her “family” at JAM started a brunch series that benefited not just their finances, but their mission to cultivate new art collectors: “You got a meal, something to drink, and a lecture from someone in the art world.” (It’s worth noting that Stevie Wonder was also a years-long member of their clientele.)

Janet Olivia Henry’s The Studio Visit (1982).

Flier for Just Above Midtown Gallery, c. 1985.

By the time its third location, a 25,000-square-foot industrial loft in SoHo, shuttered, JAM was at its most laboratory-like stage. Artists such as Lorna Simpson and Sandra Payne got more experimental (particularly via performance) than ever, which is another reason why Bryant was skeptical that “JAM could be JAM” at MoMA. So, apart from commissioning JAM alums and artists to create new groundbreaking artworks, she’s taken the exhibition outside of the museum’s walls. “Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces” ends with a wall text listing the ways in which the exhibition continues not just throughout MoMA, but also through Art Inside/Out, a collaborative series with Bryant’s urban farming initiative Project EATS.

The highlights of the latter are the very first thing that Bryant wants to discuss when she calls me from the same Harlem apartment where she and her JAM family used to cook up those dinners. The new video collaboration she commissioned from Arthur Jafa and Garrett Bradley, for example, will be on view not just at MoMA, but also at the Lower East Side and Brownsville, Brooklyn outposts of Project EATS. Meanwhile, stills from a memorable 2002 Hammons installation can be found in five bus shelters in Brownsville, and soon on a billboard by the Williamsburg Bridge.

Another highlight is Maren Hassinger’s video Industrial Nature, on view on the rooftop of Project EATS’s LES location beginning November 14. Like the original JAM, its location is significant: The work will be visible to the New York City Housing Authority residents Bryant noticed were peering out their windows when she first visited the site. “I’m very much interested in art that has not only just real-life consequence, but is also just a part of daily life,” she says, noting that she considers Art Inside/Out her most direct expression of that goal yet. “Bringing art to communities that don’t go to art institutions to experience art—which, frankly, is most of the world.”