Jacqueline Stewart Shares 10 Essential Films to Watch This Black History Month

Film expert Jacqueline Stewart’s work is steeped in the rich history of Black filmmaking. You may recognize her from the Turner Classic Movies (TCM) channel, where she hosts the Silent Sunday Nights film series—or as the director and president of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. The scholar, educator, programmer, author, and archivist served on the advisory committee of the Academy Museum’s Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971, a new exhibition that looks at the history of pioneering Black film artists, and features an accompanying high school curriculum. Inspired by an independent, all-Black-cast movie from 1923 by the same name, Regeneration revives lost or forgotten films, makers, and performers for a modern audience.

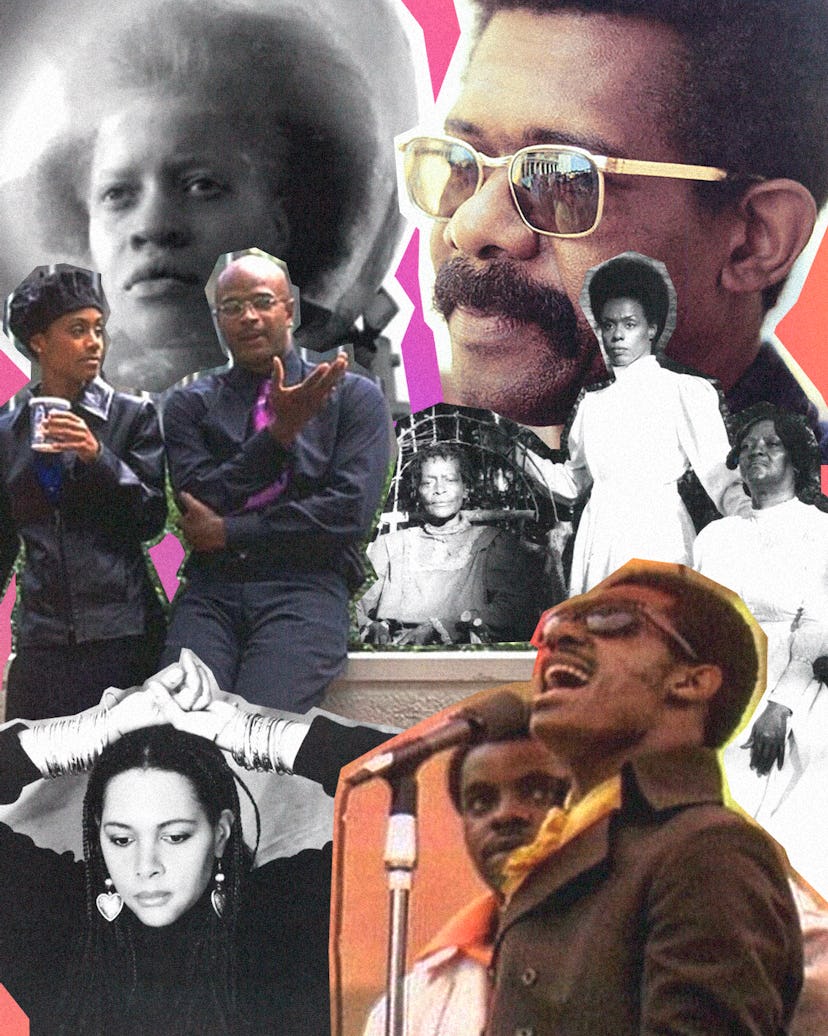

For W, Stewart has handpicked a list of ten films to watch this Black History Month and beyond, including her favorite film of all time, Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust. “I really tried to think about films that reflect on moments in Black history,” Stewart says of her picks. Read on for those recommendations, which span 62 years of filmmaking and run the gamut of genres, styles and lengths.

Daughters of the Dust by Julie Dash (1992)

This is my all-time favorite film, by a filmmaker I admire so much, Julie Dash. She was a member of the so-called L.A. Rebellion School of Black Filmmakers out of UCLA. Daughters of the Dust is about an extended Black family that lives on the Gullah Islands off the coast of South Carolina. It’s 1902, and they’re preparing to engage in the Great Migration. There’s real conflict about what it means for the family to leave behind their ties to the soil and their ancestral history, for what they’re imagining is going to be a life of modernity and opportunity. It’s gorgeously photographed all in natural light, and it takes seriously the history and the beauty of Black women.

Julie also reimagines the way slavery haunts African American people. When the family’s ancestors were brought over to the islands, they worked in the indigo fields, which was certainly true of that area. Julie does this fascinating thing where, at one point, you see that the old people’s hands are still stained indigo—really dark blue. Indigo doesn’t stain people’s hands like that, but she wanted to create a visual that was different from seeing scars on former slaves’ backs to reimagine what those scars of slavery could look like. It’s a powerful artistic approach that gets us to think about how slavery continues to have an impact on individuals, families, and our culture. That’s the kind of historical reimagination work that I love.

Streaming on Prime Video and Apple TV.

Nat Turner, A Troublesome Property by Charles Burnett (2003)

This is a documentary by Charles Burnett, another member of the L.A. Rebellion Group well-known for his films Killer of Sheep and To Sleep With Anger. Many artists have reflected on Nat Turner, who led a very bloody and infamous slave rebellion. William Styron wrote a novel about him, and there’s a lot of debate about what kind of person he was and what his motivations were. This documentary looks at all those different representations over time to show how various artists and historians have talked about him, and it questions, how do we really know the histories that we narrate? It has amazing structure, and Charles even includes himself in the film toward the end.

Streaming on Prime Video.

Sankofa by Haile Gerima (1993)

Haile Gerima, the third and last L.A. Rebellion artist on this list, made this film. Sankofa is the story of a Black model at a photoshoot in the Goree Islands of Senegal, the last stop before Africans were packed into ships and sent to the New World. She’s posing for this fashion shoot and, all of a sudden, she finds herself transported into the tunnels of one of the slave castles. It echoes in many ways Octavia Butler’s Kindred, which also tells a story about a contemporary Black woman who was transported into slavery times. The film does a lot to give us insights into what the experience of enslavement was like and why that history is not in the past—we still live with it today.

Streaming on Netflix.

Watermelon Woman by Cheryl Dunye (1996)

Watermelon Woman is the first feature by an out Black lesbian filmmaker. Cheryl Dunye, who was recently named to the National Film Registry, plays a character also named Cheryl, an aspiring filmmaker working at a video store who becomes enamored with an actress she sees playing a maid in a bunch of old Hollywood films. In the credits, this woman is only listed as The Watermelon Woman,” and Cheryl goes on a search to find out who she is. She ends up finding a foremother who becomes an inspiration to her in her pursuit of becoming an artist in her own right. It’s a hilarious, really fun, and super imaginative film shot in Philadelphia. You see all of these quirks of the lesbian community in it. And Cheryl continues to do amazing work today.

Streaming on Prime Video and Showtime.

I Am Not Your Negro by Raoul Peck (2016)

This is a reflection on the life and work of James Baldwin, done by a masterful filmmaker. Narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, the film traces reflections that Baldwin makes about race and inequality in America. Baldwin wrote a lot about it, and it’s definitely a film that people should watch to gain deeper insights into how seemingly benign Black representation in film really does shape our understanding of difference. As he always does, Baldwin gives us some pathways to rethink our assumptions.

Streaming on Hulu.

Summer of Soul by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson (2021)

An incredible film—and not just for the ways it documents the Harlem Cultural Festival, which featured luminary Black artists like Stevie Wonder, Mahalia Jackson, The Staples Singers, and Sly and the Family Stone. As a film archivist nerd, I love Summer of Soul for how it champions the importance of film preservation. It was locked away for many years by the folks who shot it, because it didn’t immediately find a commercial audience. It’s fantastic that Questlove was able to bring this footage to light. He does an outstanding job of selecting the most powerful and entertaining moments in the performances, and also in putting the footage in historical context of the Black power movement, along with the transition from the Motown era into more diverse forms. It grounds you historically, giving new insight into what you might otherwise just see as a music festival. But it was much more than that. It was a cultural celebration.

Streaming on Hulu.

Mr. Soul! by Melissa Haizlip (2018)

This film was made by the niece of Ellis Haizlip, the producer of a Black public affairs show called Soul. It was part of a wave of shows in the late ’60s and early ’70s made by and for Black audiences. They were a response to a report by the Kerner Commission, which pointed out that one of the most glaring aspects of racial inequality in this country was the lack of adequate and truthful representation of Black people in the media. So stations had a governmental obligation to give time and space to Black public affairs shows, and Soul was one of them. It might be one of the most aesthetically accomplished of these programs—a combination of musical performances and news pieces that talked about issues in the Black community, like employment, healthcare, and housing. It would be amazing if we lived in a moment where that kind of community-engaged programming was still happening. Ellis Haizlip took to heart the importance of this programming and threw himself into creating this space in an otherwise all-white television landscape for Black audiences to see reflections of themselves.

Streaming on HBO Max.

Afronauts by Frances Bodomo (2014)

Afronauts is a short by an incredibly talented filmmaker. It’s based on a historical episode in which a scientist in Zambia wanted to create a space program, and actually began putting together a ship and crew that could travel to the moon. It was obviously very under-resourced, but he was committed to this project. Frances Bodomo imagines what the experience would’ve been like for a young woman afronaut to train to go to space. It’s really beautifully shot in black and white, with a surrealist quality to it. This is a nod to Afrofuturism and the dreams of space travel and freedom, and how those become associated in the Black imagination.

Streaming on Youtube and Vimeo.

The Cry of Jazz by Ed Bland (1959)

Often, if people know things about Black film history, they know about the Blaxploitation era of the 1970s and the filmmakers who came thereafter. They may know about the Black independent filmmakers of the ’30s and ’40s, but the ’50s are really underrepresented, so I wanted to pick something from that period. For The Cry of Jazz, musician Ed Bland made this low-budget, independent film, in which we see scenes of an interracial friend group in Chicago debating the origins of the genre. The film makes the case that jazz is an indelibly Black art form, and that it foreshadows the civil rights revolution that’s about to come. We see shots of street life in Chicago, incredible real-life sequences, and Bland shows us how the rhythms of jazz express more than any other art form what the day-to-day lives and the spirit of Blackness represents. Sun Ra performs the music for this thought-provoking film. The debate scenes between white and Black intellectuals are very wooden, like, “I stand for this and I stand for that,” but this kind of homegrown filmmaking is really, really rare—and worth the watch.

Streaming on Prime Video.

Bamboozled by Spike Lee (2000)

This is one of Spike Lee’s most important films. It’s about a network television writer played by Damon Wayans who becomes frustrated by the lack of opportunities to tell meaningful stories. He decides that if he comes up with the most racist possible idea, he’ll get fired and escape his predicament. So he creates a minstrel show, casting performers played by Tommy Davidson and Savion Glover in black face, doing a lot of really racially offensive joking and word play. Despite Wayans’s hopes, the show becomes a huge hit.

Apologies for being super nerdy, but one of the things I love most about this film is the way cinematographer Ellen Kuras creates an approach using multiple digital cameras, giving it a frenetic quality. There are so many issues that come up in the film around, “What do we think is funny and why? Is it okay to laugh at racialized humor?” Using so many different cameras and points of view drives home the idea that there’s no single, definitive answer. The film ends with a prolonged montage of racist imagery across the history of Hollywood film, from Shirley Temple to Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland to cartoons, showing how dehumanizing these images have been, and making clear that the legacies of misrepresentation and stereotyping are not relegated to the past—they’re things we still actively need to think through right now.

Streaming on Prime Video.

This article was originally published on