Alessandro Michele Reflects on Making a Gucci Collection in One Week

In just five years, Gucci’s Alessandro Michele has transformed the fashion landscape with his constantly evolving, ageless, gender-fluid designs.

Five years ago, the revolution at Gucci, which jump-started a revolution in fashion, began with what appeared to be a classic loafer. Its front was made of soft black leather, decorated with the traditional Gucci gold horse-bit ornament; the back half, however, told another, more surprising story. It was completely open, like a slipper, and the footbed was lined in long kangaroo fur that spilled out in all directions. It was worn by both women (on whom you might expect the frivolity of a fur-lined mule) and men (on whom you might not) at Gucci’s fall 2015 show, in Milan. Even more challenging to the staid norms of male attire, the shoe was paired with a deep red suit that resembled narrow-cut pajamas and a patterned chiffon shirt that was tied at the neck in a soft pussy bow.

The rest of the collection was similarly bold: women in diaphanous gowns with furry, caveman-like flats; a unisex overcoat in zigzagging stripes of bright pink and maroon; men carrying Gucci handbags or wearing wallpaper-floral-print suits. It was a dramatic departure from the previous hyper-sexy Gucci era, which had been wildly successful during Tom Ford’s ’90s and early aughts tenure, but less so after his successor, Frida Giannini, took over.

“I thought I was going to lose my job,” Alessandro Michele, the creative director and designer of Gucci, told me on a sunny winter day in Miami. He was in the city—for the first time ever—for a Gucci and Snapchat event taking place during Art Basel Miami Beach. Michele has a baby face under his long hair and full beard, and, like a very curious child, he is immediately engaging. He was sitting on a velvet sofa in his suite at the Faena Hotel, wearing a straw hat, burgundy velvet shoes accented with pearl embroidery, jeans, and a plaid flannel shirt in shades of rust, blue, and brown that he had styled over a pink T-shirt and under a maroon vintage Aran cardigan. He had rings on every finger, and several chains around his neck.

“The entire beginning felt like an accident,” he said. “Frida Giannini was gone, and I was ready to leave the company. And then Marco Bizzarri [Gucci’s president and CEO] said, ‘Let’s have a coffee.’ He had heard of me because I was not only in charge of accessories and jewelry at Gucci but I was also the creative director of Richard Ginori [the -porcelain tableware company]. Marco came to my house and said he was fascinated by how it looked.” Michele, who has now outfitted the Gucci stores in the same manner as his home—deeply patterned rugs on top of other rugs; embroidered throw pillows that often feature images of his two dogs; worn velvet couches in jewel tones—has a deep love for color and decoration. In every aspect of his designs, whether it’s a handbag, a dress, or a shoe, he likes to take a classic idea and subvert it.

Michele didn’t reveal his plans for the first show to Bizzarri—he didn’t have time. “Marco thought I was the right person to do the collection,” Michele recalled. “He told me, ‘I need you to show a collection in one week. You have five days to design it.’ I said, ‘Why not?’ I love this kind of challenge.”

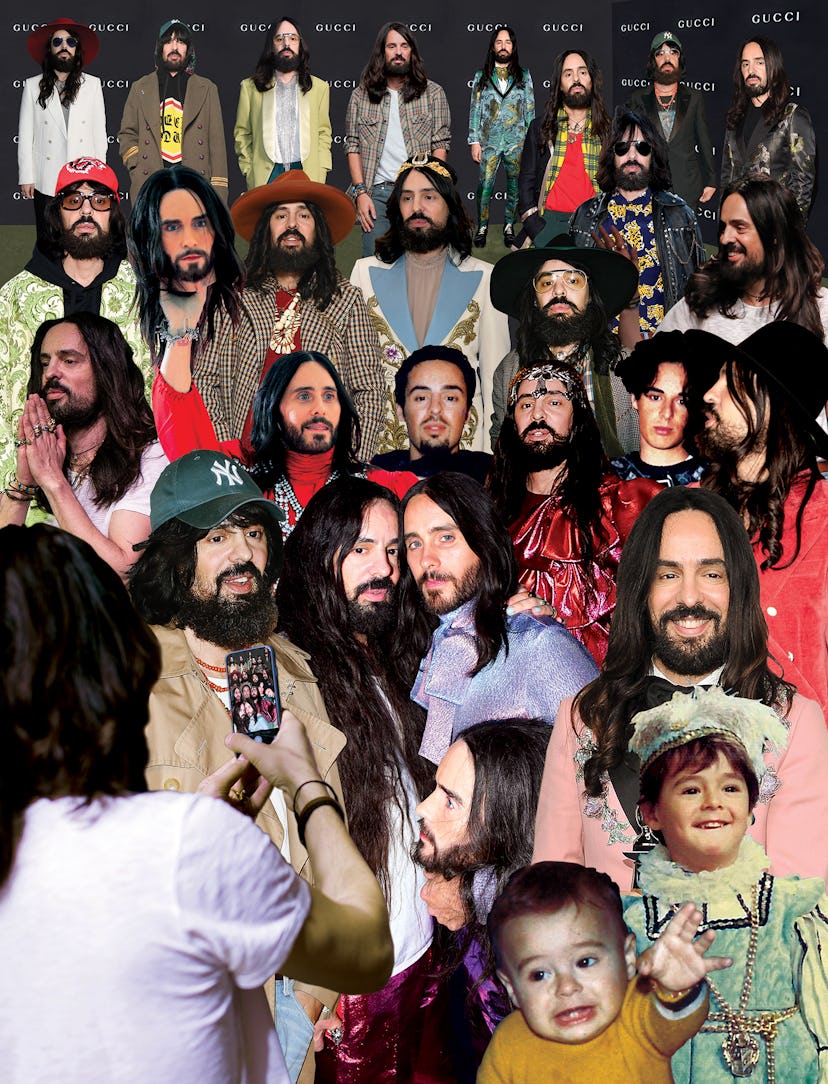

OUTSIDERS ARE IN Celebrities like (from left) Iggy Pop, Cate Blanchett, Chloë Sevigny, Lou Doillon, Dani Miller, Soko, Ana Kraš, Devonté Hynes, Curtis Harding, Zumi Rosow, Alessandro Borghi, Jared Leto, Kirsten Dunst, and Rihanna have been instrumental to Michele’s success.

Much has been said about how Michele’s work helped usher gender fluidity into fashion. And while it’s true that putting pussy bows on men felt like a risk just five years ago, there was something deeper about Michele’s approach: He spoke, in a broad context, to the idea of not belonging. “I was an outsider, and I still am an outsider,” Michele said. “They call me the ruler of gender fluidity, but to me, I was just pulling out beauty. Conventionally beautiful people have always confused me. The more you are a hybrid—young but old; male but female; female but male—the more you look interesting.” His vision was statement dressing, but of a very particular sort, in which gender and age were not delineated. “In the beginning, the guys around my office would say, ‘You adore things that are ugly or strange,’ ” Michele continued. “Like the shoe with the fur. They were saying, ‘Oh my god, Alessandro is crazy! And you’re putting it on a man and a woman! Oh, no!’ ” Michele smiled. “It was our biggest seller. We did a non-fur version to be safe, and we only sold the crazy ones. People like to be crazy and special and chic!” He paused and took a sip of water. “To do the wrong things in the right way is complicated,” he said. “But that is my idea of beautiful.”

A month earlier, Michele had been in Los Angeles for the Art+Film Gala at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The yearly event honors a filmmaker (for 2019, it was Alfonso Cuarón, the director of Roma) and an artist (Betye Saar, the groundbreaking assemblagist). Gucci has underwritten the event, which is considered the West Coast’s equivalent of the Met Gala, for years. Nearly every bold-named attendee was wearing Gucci: Donald Glover, in a white silk shirt with a loosely tied bow under a brocade tuxedo jacket; Salma Hayek Pinault, in a tight sequined halter dress; Ava DuVernay, in a gown that seemed to be made of pleated silver Mylar; Greta Gerwig, in a 1920s-inspired, heavily beaded pink gown.

Michele’s designs were everywhere, and yet everyone in the room looked individual, as if they had picked out an outfit that best revealed their personality. Michele was standing in the middle of the dining room, near his close friend the actor and musician Jared Leto, who was talking to Giovanni Attili, Michele’s longtime boyfriend. Michele was wearing black pants with a white double-breasted dinner jacket over a T-shirt with a geometric test-pattern design that was quite hypnotic, a wide-brimmed red hat, and matching red tassels on a cord necklace. “Fashion, for a long time, has been in a box,” he said as he looked around the crowded room. “ ‘That’s fashion;’ ‘That’s not fashion.’ Fashion is bigger than that! Let people be free.”

At that moment, Billie Eilish, Michele’s tablemate at dinner, arrived. The LACMA gala took place a few months before the singer would win five Grammys. “I love the way she looks,” Michele said about Eilish, who was in a Gucci tunic and board shorts, as she shyly said hello and sat down. Just like Michele, Eilish was the weird outsider who became extremely popular. In fact, Eilish may be the perfect incarnation of Michele’s sense of the brand: a self-proclaimed misfit who sings about alienation, yet engages millions of fans.

Michele, 47, has always had a maximalist, color-drenched sensibility. He grew up in Rome, and was first inspired by his aunt Giuliana—his mother’s twin—who worked, as his mother did, in the film business. “She really let me think that the things you say and do and wear are a big part of your freedom,” Michele said. “When I was 6 years old, I wanted open clogs—like the shoes you wear on the beach in the summer, but I wanted them in the winter! I would have colorful socks with my clogs: yellow, green, orange. My mom said, ‘No!’ And my aunt said, ‘Go ahead!’ Even now, I want to do the same thing: wear socks with sandals. In everything, I want to show that journey from conformity to creativity.”

When he was 23, Michele applied to work at Versace, which was, in the ’80s and early ’90s, the red-hot center of Italian fabulousness. “I was in love with Gianni,” he recalled. “Versace understood fashion as a great language.” But the company did not hire Michele, so he went to Fendi, where he designed accessories, and then Gucci. “Before Tom, Gucci didn’t exist as a brand,” Michele said. “I may have made some adjustments, but I built what I’ve done on his foundation.”

Before Michele’s first collection, the stock for Kering SA, Gucci’s parent company, was struggling. After Michele, there was an immediate double-digit growth in sales, and Gucci continues to be a juggernaut. But once the surprising becomes commonplace—nearly every designer’s collection is gender-fluid these days—it becomes necessary to innovate further. “That’s why we are rethinking the ad campaign,” Michele said. He was excited about the prospect of shooting in Los Angeles a couple of days after the LACMA event with the filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos, who directed The Favourite.

NEW MODEL ARMY A sampling of Michele’s collections from the past five years.Alessandro Michele Collage: Photographed by Venturelli/Getty Images for Gucci; Photographed by Ernesto S. Ruscio/Getty Images for Netflix; Photographed by Daniele Venturelli/Getty Images for Gucci and Maxxi; All other images Courtesy of Gucci. Gucci bus stop: Chloë Sevigny: Photographed by Mike Windle/Getty Images for LACMA; Rihanna: Photographed by Raymond Hall/GC Images; Kirsten Dunst: Photographed by Gisela Schober/Getty Images; Jared Leto: Photographed by Taylor Hill/FilmMagic; Soko: Photographed by Rabbani and Solimene Photography/Getty Images for Gucci; Cate Blanchett: Photographed by Jeff Spicer/Getty Images; Zumi Rosow, Lou Doillon, Alessandro Borghi, Ana KraŠ, Devonté Hynes, Iggy Pop, Curtis Harding, and Dani Miller: Photographed by Vittorio Zunino Celotto/Getty Images for Gucci. Gucci park: Look from Fall 2015 men’s wear, Looks from Fall 2016 ready-to-wear, looks from Fall 2017 ready-to-wear: Photographed by Catwalking/Getty Images; Look from Resort 2016: Photographed by Fernanda Calfat/WireImage; Looks from Resort 2017: Photographed by John Phillips/Getty Images for Gucci; Looks from Resort 2017: Photographed by Karwai Tang/WireImage; Look from Spring 2017 men’s wear: Photographed by Pietro D’aprano/Getty Images; Look from Resort 2018: Photographed by Venturelli/Getty Images; Looks from Spring 2019 ready-to-wear and look from Spring 2020 ready-to-wear: Photographed by Vittorio Zunino Celotto/Getty Images for Gucci.

At Michele’s request, Lanthimos had already done an unsettling series for him, which was turned into a limited-edition book. The pictures are of androgynous models in Gucci clothes interacting with fully nude geriatric men and women who are painted chalk white; shot in the gallery of an 18th-century Roman villa, they convey an overwhelming sense of mortality. A ghostlike woman looks under the skirt of a sleeping (or dead?) girl. An elderly naked man sits next to a young woman dressed in black. This is far, far away from the joyous gatherings in Gucci’s earlier ad campaigns, in which, for instance, Harry Styles was photographed with a cute pig and baby goats and lambs. “I decided to change because Yorgos can see something that I can’t, which is the speed of life,” Michele explained. “Fashion is fast, and life is fast—there is something magnificent about showing that, even if it isn’t easy to look at.”

Fashion has long been afraid to display any sense of age or, worse, decay. Perhaps even more radical than Michele’s embrace of gender fluidity is his strong belief that age shouldn’t be a factor when designing clothes. “You have to love things that are not so young!” he said. “Everyone will age—you can’t change that, and it’s a crazy thing to fight. I didn’t push women to dress like young girls, I did the reverse.”

Back in Miami, Michele was hosting the big party with Snapchat to celebrate Gucci-designed glasses with built-in cameras that could record short films. The director Harmony Korine, who also did a limited-edition book for Gucci, had directed a mini movie using the camera-glasses; it would premiere at the event. The glasses would be displayed, but they were not going to be produced for sale. “I wanted to do something just for one night,” Michele explained. Still, he seemed apprehensive about the frenetic pace of technology today. “If I made a movie—and I would love to make a movie—I would want it to last,” Michele said. I asked him if he had an idea for a film. “I was thinking less about the genre of movie I would make and more about the structure. I don’t want there to be a conventional beginning or an end. Let’s do a movie that starts in the middle! I can’t remember when I was born, and I don’t know when I’ll die, so I’m in the middle.”

He laughed at this notion. Perhaps this was a way of assuaging anxieties about something Michele had told me earlier. “One day,” he had said, “I imagine myself not working in fashion. Ever since my first collection, I’m always thinking that I could be fired.” The idea of sudden termination actually seemed to motivate him. He shrugged. “It’s not a bad way to keep yourself excited about the job. For me, being the designer at Gucci is like being in a complex relationship: It is never easy, and it shouldn’t be—but it is always interesting.”