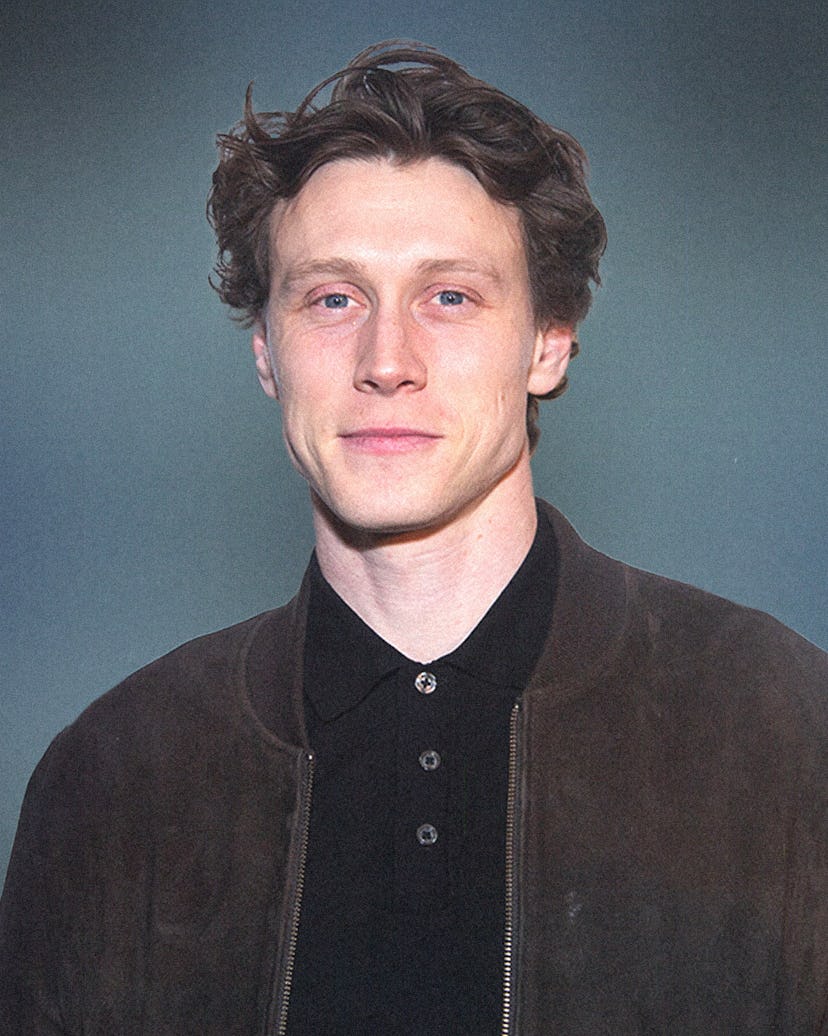

George MacKay Steps Into His Villain Era With a Pair of Dark Films

In Femme and The Beast, the British star of the award-winning 1917 pushes himself to the extremes of toxic masculinity.

When George MacKay was cast in Sam Mendes' award-winning 1917, he had no idea the film, a harrowing drama about WWI soldiers filmed as if it were in one take, would go on to land 10 Oscar nominations and three wins. "Ironically, the longest time I've not worked was when we were promoting that film," he says.

MacKay has been acting consistently since childhood, but 1917 was a breakthrough for the 32-year-old, and his first major studio press tour. He played lance corporal William Schofield, a paragon of nobility exposed to the horrors of trench warfare as he attempts to deliver a crucial message to stop an attack. You can see the innocence seep from his wide eyes as he completes his mission.

After that film's awards run, however, the world shut down with the pandemic. But MacKay forged ahead and now he's emerging with two new roles that find him exploring the darkest corners of humanity.

First, there’s the thrilling, tense, queer neo-noir Femme, in which MacKay plays a closeted gay man whose internalized homophobia leads him to viciously assault a drag queen (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett), who later gets her own revenge. In Femme, directed by Sam H. Freeman and Ng Choon Ping, MacKay brims with put-upon arrogance as Preston, a man so uncomfortable in his own skin that he reacts to others with violence.

Nathan Stewart-Jarrett and George MacKay in Femme

Then there's French director Bertrand Bonello’s romantic sci-fi drama The Beast (La Bête), loosely based on the 1903 Henry James novella, The Beast in the Jungle, in which he and Léa Seydoux (Dune: Part Two) play lovers fated to meet under catastrophic circumstances throughout many lifetimes.

MacKay plays Louis, whom we meet under these circumstances: In 1910, he woos Seydoux's Gabrielle, who is married to a doll factory owner. In 2014, he's an Elliot Roger-styled incel ranting about women from a car outside the mansion where Gabrielle, now a wannabe actress, is house-sitting. And in 2044, they meet again as she considers a procedure that will make her less emotional and more employable in this strange future.

"The exciting thing I found about Louis is he is Gabrielle’s beast," MacKay says over coffee one chilly afternoon in New York last month. "He’s the thing that destroys her every time. That was my throughline.”

MacKay didn't know much about incel culture before signing up for The Beast, in which provocateur Bonello uses the exact words from the manifesto of Elliot Rodger, who killed six people near the University of California, Santa Barbara campus in 2014. "I was mindful of the ramifications of giving any sort of limelight to [the words]," MacKay says. "But at the end of the day, I'd say the moral of that part of the film is not to be ruled by fear and how fear can turn into spite. I thought it was a worthwhile cautionary tale."

Léa Seydoux and George MacKay in The Beast

Off-screen, the London-born Mackay is exceedingly courteous. After a miscommunication leads us to two different locations of the same coffee shop, I arrive flustered and late to our interview. Still, he greets me with a hug and a latte. Since 1917, MacKay has become the father to two children—and parenthood has shifted his approach to choosing roles, even when that means signing up for material as dark as Femme and The Beast.

"I had this incredible opening up when my family came about," he says, explaining that having a child made him think more deeply about how we present ourselves to the world, to our families, and the secrets we might keep in crafting our outward identities. "That theme draws you to people who are hiding or expressing things on an extreme level,” he says. “I subconsciously was turned onto that."

The features were shot almost back-to-back in the summer of 2022. For Femme, MacKay wanted to bulk up his body. Stewart-Jarrett's Jules, the performer assaulted by MacKay’s Preston, is a classic drag artist, but Preston wears his machismo like a form of drag, too. In addition to putting on muscle mass, MacKay worked with hair and makeup to design Preston’s shell down to his tattoos.

"His outer layer was really important because the drag aspect of the film is such an integral theme," MacKay says. "There was a very detailed story to be told in how he wanted to be seen."

Playing such complicated, violent characters meant that The Beast and Femme became exercises in empathy for the actor. "That's one of the things I think is beautiful about the job,” he says. “You have to understand or empathize with whatever your character is doing.”

Next up MacKay will continue to ponder life's existential questions, this time with Tilda Swinton and Michael Shannon in The End, a musical from renowned documentarian Joshua Oppenheimer about the last family on Earth living their days out in a bunker. Mostly he's operating on what he calls "gut instinct."

"I'm just a fan of cinema," he says. "And big cinematic visions."

Femme and The Beast are both currently playing in theaters.