To be an architect or an artist?

Donald Judd found himself preoccupied with this vocational debate while he was stationed in Korea during 1947 as an 18-year-old engineer with the U.S. Army. The late legend ultimately pursued both paths—while he remains one of today’s most sought-after contemporary artists around the globe, his expansive architectural projects (particularly in Marfa, Texas, where he lived and worked from the late 1970s until his death in 1994), have transformed the desert city.

Revisiting the country that helped crystallize his career, gallerist Thaddaeus Ropac has opened Judd’s first Korean solo exhibition in nearly a decade, in conjunction with Frieze Seoul. On view until November 4 at the Austrian gallery’s Seoul Fort Hill outpost, “Donald Judd” provides a concise overview of the artist’s material evolution, from his early 1960s paintings to his floor boxes, “stacks,” and prints of the 1980s and 1990s. According to the show’s curator, Flavin Judd—the artist’s son and artistic director of Judd Foundation—Donald’s departure from representation reflected his desire to “make work that is not hiding something.” Below, Flavin Judd explains the power in taking his father’s work at face value, as well as the surprising parallels between Korean aesthetics and Donald Judd’s philosophy.

With this tightly curated show, were there any works you knew you wanted to include from the get-go?

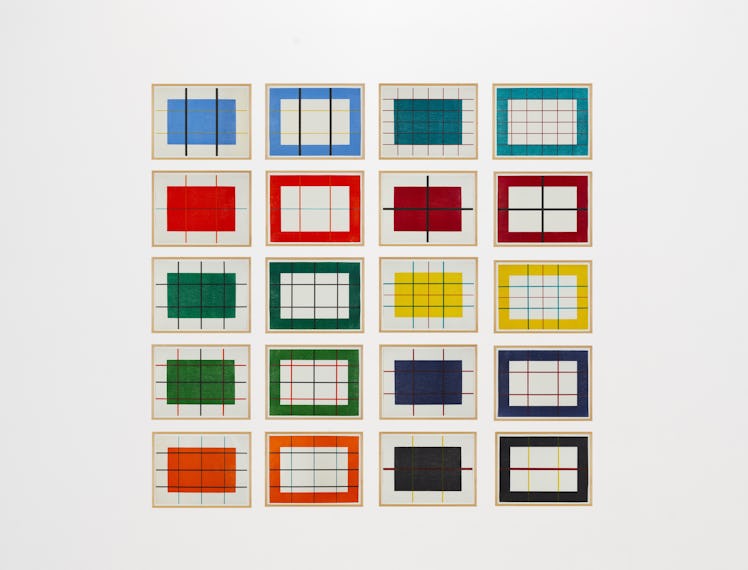

I think the print set was the first, because it can really hold its own on a long wall. Don initially started those prints in the ’90s when he was in Korea. He bought some hanji paper [traditional Korean paper made from mulberry tree bark] off the street and brought it to Robert Arber [Judd’s printmaker] in Marfa to make a set of prints. But it turns out you can’t use hanji paper to make prints because it’s not chemically the right formula, so the whole project got put on hold. Years later, we revisited the project and made custom paper to finish the prints.

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1960.

What was your father’s experience being stationed in Korea like? How influential was the country on his work?

As an 18-year-old from the Midwest, Don must have been quite surprised to experience Korea’s fascinating and complex culture. When he spoke about his time at the airbase, however, he mostly discussed his relationship to his crew because he really respected their experience. I don’t think he got to spend much time outside of the base because it was very tightly controlled. He only returned to Korea as a visitor in the early 1990s.

Korea was definitely special to him because of the connection to his own past. There are some buildings at Las Casas [the last and largest ranch Judd purchased, which is located 80 miles outside of Marfa] that my father specifically wanted to have “black Korean tiled roofs.” It seemed like an impossible request before I went to Korea, but now it seems totally obvious, and we’re working on getting them.

Donald Judd in Marfa, Texas in 1993.

Flavin Judd

The exhibition catalogue parallels the way Donald and Korean aesthetics value space and emptiness. Can you explain the significance of Donald’s deliberate use of space and how it echoes other cultures?

Don’s stacks were the first time in art that space itself became part of the artwork. In certain cultures, the emptiness of something takes up a space that cannot be violated, and you work around that. For instance, in the old Parisian houses on apartment blocks, there is always a courtyard in the middle. That’s different from an American type of building where there is no space, and everything is filled to capacity.

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1985.

What do you think are the greatest misconceptions surrounding Donald’s work?

I think the biggest mistake is to believe that his work is somehow minimalistic. The space between the units of his stacks is not an allegory to the space between stars. Don is not interested at all in allegories or myths. He wants a physical experience and is inviting viewers to be as aware of their immediate surroundings as possible. That’s actually as maximalist as you could get because it’s very much about the physical.

For Don, as an atheist, this is all we get—maybe 60, 80 years on Earth out of the billions of years that the universe has been around. To exist is a privilege. That’s as exciting as it gets, so you should enjoy it. The banal things that we take for granted, like the movement of the sun or the way the colors change with light, or the shadows or space between things, are absolutely amazing. What’s interesting to him is what’s here now.

Donald Judd, installation view, Thaddaeus Ropac Seoul.

How does Donald’s emphasis on dimensionality affect the experience of viewing his work?

You’re supposed to be able to see over the works, so that it’s clear that they’re three dimensional. That’s why Don made many floor works because you’re forced to walk around them. The dimensionality is also what makes them challenging to photograph. I had a photographer tell me that shooting in Marfa is really hard because the architecture is not designed from one perspective. I almost always find that the sign of a good artwork or building is that it doesn’t photograph well.