Ethel Cain’s America

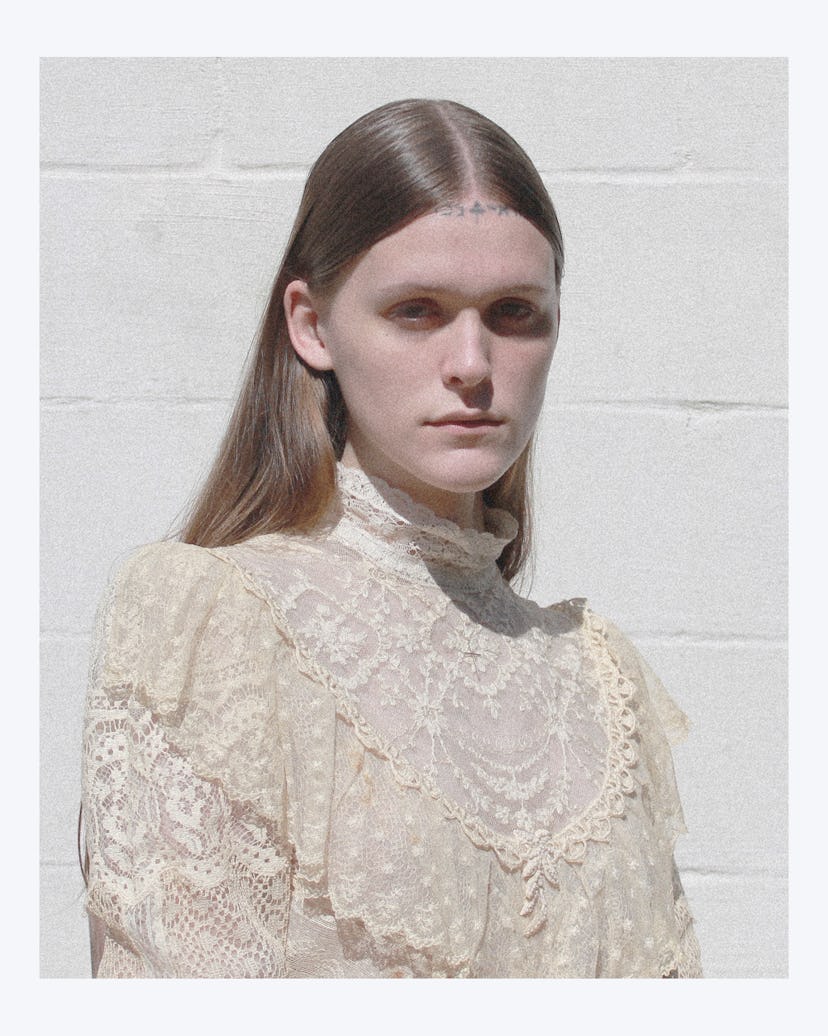

With the release of her debut album, Preacher’s Daughter, the musician invites you into her Southern Gothic fantasy.

The musician Ethel Cain is no patriot. So why does she appear on my computer screen wearing a T-shirt with an American flag printed on its front? And why is there an American flag hanging on the wall of her modest home in Alabama, whose wood-paneled walls and old-timey furniture evoke imagery of Little House on the Prairie instead of an emerging pop star’s pad? “I’ve always been very much about, keep your friends close and your enemies closer,” the singer-songwriter, whose real name is Hayden Silas Anhedönia, says with a wry smile.

The story of the flag is this: Cain, who hails from a small town in Northern Florida called Perry, grew up Southern Baptist in a family full of proud Americans; “country boys,” as Cain describes them, many of whom served in the U.S. Army. “Growing up, it was drilled into me and my siblings: Don’t let the flag touch the ground. Don’t let it get dirty, or faded, or torn. Don’t hang it upside down,” she tells me. So when Cain accidentally kicked up a ratty, ripped, and dust-covered American flag left in an abandoned town near her current place in Alabama, she knew she wanted to keep it.

“I have my cross necklace on, and I have my American flag t-shirt on—and I’m not a huge fan of either of them,” she adds. “I just keep them as close to my heart as possible, in my own way of staying above them. I think that’s why I talk so much about it in my art, because it’s easier to get the upper hand: I’m not gonna get rid of you, so I might as well have this power over you.”

The religious and political iconography associated with Cain’s childhood have become the inspiration for her art form. The 24-year-old musician has been making hazy ballads and orchestral tracks since she was 15, but burst onto the scene with her Gothic Americana style in 2019, with the release of her first EP, Inbred. Since then, she’s signed a deal with Prescription Songs, created her own record label Daughters of Cain, and put out her highly anticipated debut album Preacher’s Daughter on May 12. Her fuzzy alt-pop has captured the attention of record labels, fashion brands, and rapt listeners alike, giving Cain the opportunity to dive headlong into stardom. (In all honesty, though, she’d rather not: “If it was up to me, I would just sit in my house and never leave, and be a nobody.”) But with the release of Preacher's Daughter, Cain has agreed to play the game of album release promo. She has plans to travel to Paris in the weeks following this interview—her first time flying out of the United States. “It’s definitely a little nerve wracking, but I’m choosing to see it as something fun that you get to do and not a chore that you have to do,” Cain says. “I’ve been trying to rewire my brain.”

Cain’s mind is attached to her surroundings in the American South. She calls the region, with all its conservative leanings and cultural paradoxes, a “weird comfort.” Perhaps that’s why the artist is able to approach her musical subject matter with a critical, yet somewhat loving eye. She speaks of her super religious, nationalistic, and traditional upbringing with equal parts nostalgia and a kind of sobered frustration.

Her childhood began and ended with the church: Cain’s father was a deacon in their First Baptist congregation, and her mother was in the choir. She spent at least four days out of the week in kids choir and youth group. “That small-town church was my whole world,” she says. “It was all-consuming. I wasn’t allowed to know anything outside of it.” The church turned out to be Cain’s first exposure to music: she’d often sit through her mother’s choir practice and spent weeks in the summer attending Vacation Bible School, a musically based getaway for the parish. “My whole life was always singing, always, always music all the time,” Cain says. “It’s no wonder that I fell in love with it, because it’s such a constant force in my life.”

Other than hymns and liturgical tunes, Cain’s parents kept things family-friendly in the house. They’d listen to Karen Carpenter, Steve Miller Band, and Christian contemporary artists—and, on occasion, if the musician found herself alone in her father’s truck with him, he’d turn on some Lynyrd Skynyrd. (“He’d be like, ‘Don’t tell your mom,’” Cain recalls.) She began taking piano lessons at eight years old, playing classical music. “I think that has lended itself to the melodrama that I find permeates my life, still,” Cain says.

In her young childhood, Cain describes herself as being close with her family—but when she hit adolescence, “it was made clear to everyone that I was not like other people,” she says. “Whenever I started to develop, I started to come into my own as a trans woman.” It was an instant war. “We were a house divided,” Cain adds. “It was me versus my whole town.” Around the age of 16, her attendance at church began to wane—she blamed it on a busy schedule taking dual-enrollment classes at a nearby community college, but in reality, she couldn't reckon the politics within the church and the actual scripture they followed. “Every church we went to, it never felt super right,” she says. “It never so much for me was about god. It was more for me about the way people were interacting with each other in the name of god. All of the personal drama was really weird. I was like, god does not even feel like he’s in here. I’m spiritual in my own way now, but Christian religion doesn’t really go further for me than just fodder for my artwork.”

Cain began making music by using the Garage Band app on her iPod Touch and a MacBook her grandparents and parents pooled money together to buy as a graduation gift. Her very first song, a track called “Altar” was highly experimental. “I didn't know anything I was doing, production-wise,” Cain recalls. “But I made the song in one night.” She posted it on SoundCloud, and continued making “super ambient, vocal-heavy songs with organ sounds, weird synths, and way too much reverb” in the months to follow. Those tracks went onto Spotify and Apple Music—catching the attention of fellow artists like Nicole Dollanganger and the Midwestern emo rapper Lil Aaron, who grew fond of her sound.

Dollanganger and Lil Aaron both connected with Cain through Instagram—Cain took a Greyhound bus from Florida to New York City to attend one of Dollanganger’s concerts, and ended up opening for a Chicago concert of hers. Meanwhile, Lil Aaron invited Cain to come to Los Angeles to meet the team at Prescription Songs (including Dr. Luke, the producer and polarizing music industry figure who heads up the publishing company). She played them three demos that would come to be central pillars of Preacher’s Daughter, including the song “A House in Nebraska.”

The making of that track galvanized the entire album. Cain had previously begun working on the record in early 2018; for about eight months, she created an entirely different project. Its sound, name, and feel was nothing like Preacher’s Daughter. While downloading samples for the other project, she stumbled upon a piano sample that she couldn’t get out of her head. “It just hit me,” she says. “I was sitting on the bedroom floor in this old house I lived in, in Florida. The song just wrote itself in, like, 20 minutes—it was a big, dramatic, piano ballad.” She scrapped the previous project, changed the name, and began working on what became Preacher's Daughter, all of which revolved around this proverbial house in Nebraska she’d dreamed up in her head. “I saw Nebraska as the center of America, a wide open expanse, an open wheat field that just went on forever and ever,” she says. “It was this empty place that I would imagine myself running away to someday, being completely alone with the love of my life forever. It’s heaven on earth—you’ll never be bothered again.”

Despite Nebraska becoming a faraway dream of a better place, and a centerfold for the album—Preacher’s Daughter is set in the patriotic and religious South, like most of Cain’s music. Even her very first EP, Inbred, pokes fun at the stereotypes associated with a Southern lifestyle. “Growing up in the South, you hear no shortage of jokes about marrying your cousin,” she says. “But a lot of my music is about intergenerational trauma and problems that are bred into your family—that carry over through bloodlines.

“[When I made Inbred,] I was not an artist. I barely had a following at all. So I was like, Oh, there are no consequences,” she adds. Presently, Cain says she’s trying to get back to that place, making music just for herself, without worrying about what others might think. “Going from absolutely nobody to getting a billboard in Times Square, it’s been a lot to process in the past two years,” she says. “I made this record so specifically to my tastes—and right at the end, I made some changes based on my own anxieties about: Is it gonna get good reviews? Is it gonna do well in the press? Are people gonna like it? Are they gonna stream it? Moving forward, I’m just putting my phone down. I don’t wanna think of myself as an artist that is any bigger than I was when I started making music. My whole world exists in this room, with my guitar, my piano, my computer, and my words.”