Gen Z Made Emo Cool Again

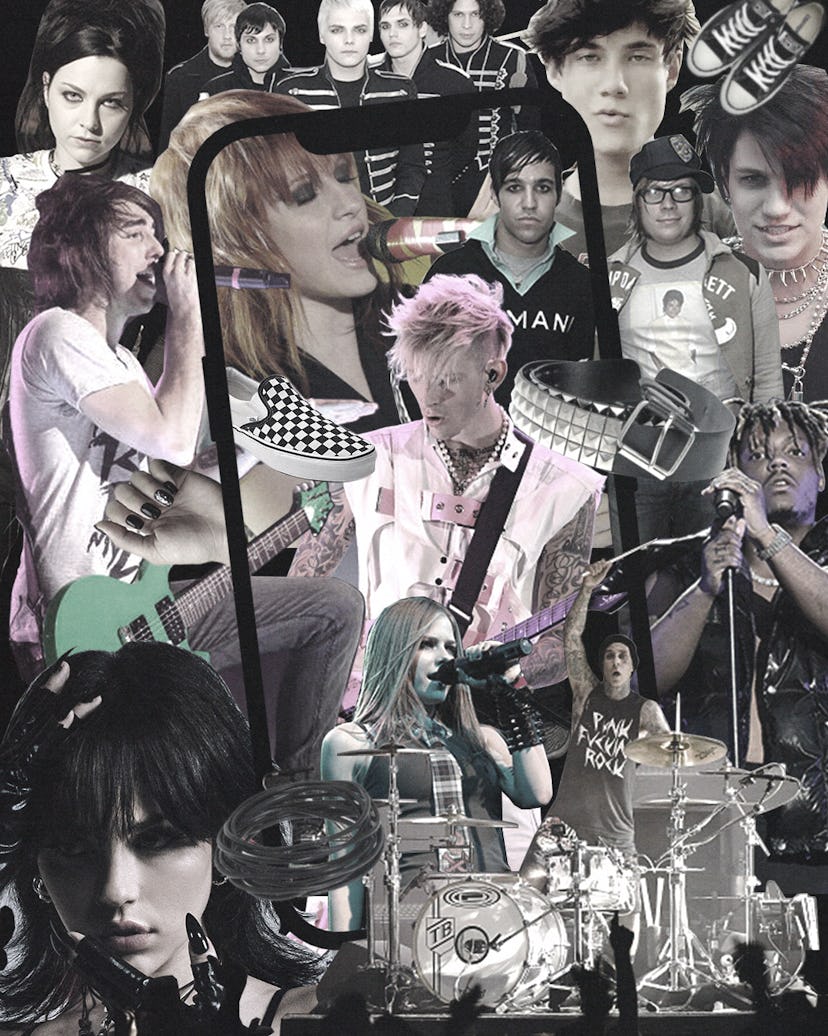

In January, Alex Gaskarth, the frontman of the band All Time Low, opened TikTok to discover thousands of videos with the hashtag #emophase made using “Dear Maria Count Me In,” a song his band released in 2007. A Domino's pizza delivery man, the Youtuber Trisha Paytas and countless others looked into the camera and made the same joyful declaration: “Mom, it was never a phase. It’s a lifestyle!” before belting the song’s first line, written roughly 15 years prior. “It was a weird, shocking but also very welcome moment,” Gaskarth told me over Zoom last month. As a Millennial who rocked a pair of checkerboard Vans, agonized over my Myspace song choice and cried to My Chemical Romance in the early 2000s, I also found myself bewildered and delighted by a TikTok trend that has people professing their adoration for a style of music that went almost tragically out of fashion after its mainstream peak in 2010.

These “coming out” videos are just one trend in a tidal wave of 2000s, emo-pop themed content (#emophase has now accrued over 766.8M views on TikTok) which include music ID challenges with text that reads: “if you know all of these songs you’re the most damaged one in the family,” eyeliner-laden and side-swept-banged #scenequeen makeovers and tutorials on how to dress like a Hot Topic employee in 2005. The sudden spike in nostalgia for this somber genre makes sense in the midst of a global pandemic, since the quarantine lifestyle eerily echoes the teenage conditions that allowed the 2000s “scene” subculture to thrive in the first place. Coronavirus has stripped us of our freedoms and sentenced us to wallow in isolation in our homes, desperately searching for connection and community online like brooding adolescents without driver’s licenses.

Trapped in an emotionally overwhelming reality, it's understandable that Millennials have been yearning to relive the sonic catharsis of their #emophase(s); meanwhile, Gen Z (who make up 60% of TikTok users) are finding solace in the romanticized version of a period in music history they never experienced firsthand. “It’s interesting how, when an era gets perceived a second time around, it gets reimagined and distorted,” Gaskarth said. “The funniest thing about all of this is that we never even considered ourselves an emo band.”

Emo music started in the basements of Washington, D.C.’s hardcore scene in the mid ’80s with bands like Rites of Spring and Embrace, who inspired the subsequent wave of ’90s bands, like The Promise Ring, Sunny Day Real Estate, American Football and The Get Up Kids. In addition to blending pop elements (like catchier melodies and variations in tempo) into the austere and intense soundscapes of hardcore and punk, they deviated from the hyper-masculine, “middle-finger up” attitudes that were pervasive in underground rock by writing introspective, poetic lyrics about pain, suffering and alienation. Outsiders tagged them with the patronizing label “emo” (short for emotional hardcore), a word previously used as an insult, meaning melodramatic or pathetic. Almost every band associated with the genre has publicly denounced it. “Being called emo is a scarlet E across your guitar strap—a mark of shame or some reason to please ignorance,” author Andy Greenwald wrote in his 2003 book, Nothing Feels Good: Punk Rock, Teenagers and Emo.

In the new millennium, bands like Dashboard Confessional, Hawthorne Heights and Jimmy Eat World began to appeal to a more mainstream crowd, eventually paving the way for the superstars of the stadium era of emo-pop in the mid 2000s. Fall Out Boy (whose first singles “Sugar We’re Going Down” and “Dance, Dance” both became top 10 Billboard hits) Panic! At the Disco (whose first album went triple platinum) and Paramore (whose second album was nominated for a Grammy) sold millions of records to misfit suburban teens and became global rock sensations.

Meanwhile, the emo aesthetic became a pervasive alternative to the era’s reigning normative trends, like Juicy Couture tracksuits, Ugg boots, Von Dutch trucker hats and bedazzled True Religion jeans. The mall goth look (linked to franchise stores like Hot Topic and Spencers) flourished among emo-pop’s substantial fandom, who wore things like black jelly bracelets, fingerless gloves, striped hoodies, thick studded belts, black nail polish. These teens were key players in popularizing new emo music on platforms like Myspace, but also increased the genre’s associations with taboo subjects, like sexual experimentation, self-harm and depression. The cringey stigma of the “emo” label not only endured throughout its radio heyday, but perhaps even increased, despite the music’s mass appeal. My Chemical Romance frontman Gerard Way, the nonconsensual poster boy for mall goth emo, called the genre a “pile of shit” in an interview in 2007.

Now, long after that boom and subsequent bust, emo’s reputation has transformed. Musical ingenues like Lil Peep and Juice Wrld, who merged the confessional agenda and dark sounds of emo with trap beats and droning rap delivery laid the groundwork for this shift in perception. These artists, who sang foreboding lyrics about their struggles with heartbreak, addiction and suicidal ideation, were celebrated for deviating from the capitalistic bravado of radio rap and became the anti-heroes of late 2010s youth culture. Their success with young listeners has helped illustrate that Gen Z, who were born on a dying planet in the middle of an economic recession, reared in the Trump years, and are now coming of age in a global pandemic, are looking for alternatives to the polished and privileged celebrities who dominated the Instagram era. The Billie Eilish generation craves a specific set of qualities from their stars: vulnerability, imperfection and transparency about emotional hardships. Now, with conversations around mental health not only normalized, but somehow even expected from musicians, the emo aesthetic and ethos of the early Millennium is the pinnacle of cool.

Rapper turned rockstar Machine Gun Kelly has emerged as the figurehead of Gen Z TikTok rock, which combines the indulgent and upbeat sounds of pop punk with the darkness and weight of emo sentimentality. In September, Kelly released Tickets to My Downfall, a collaboration with Blink-182 drummer Travis Barker, a leading figure amidst the genre’s revival. In the chorus of the album’s opening track, Kelly sings about self harm and suicide: “I use a razor to take off the edge/ Jump off the ledge, they said” over a high-energy and danceable beat. The album, which included a nostalgic cover of Paramore’s “Misery Business” that went viral on TikTok in the fall, hit number one on the Billboard charts in October of 2020. The album’s outstanding commercial success has recalibrated the landscape of the music industry and inspired many other artists to follow Kelly’s lead. In January, Kelly followed the album with Downfalls High, a “rock opera” he made with fellow pop-punk artist MOD SUN. The 50 minute film, which has already racked up 15 million views on Youtube, features a cast of Kelly and Barker’s headlining collaborators like Yungblud, Trippie Redd, Iann Dior, as well as newcomers and TikTok heartthrobs Chase Hudson (LilHuddy) and Jaden Hossler (Jxdn), who have recently launched rock careers with Barker’s help.

While all of these rising stars have consciously marketed themselves as pop-punk, the echoes of emo themes and scene style are pervasive in this new music and its internet friendly image. LilHuddy, who has over 30 million TikTok followers, has described his upcoming album (produced by Barker) as “hardcore sad music that’s gonna be relatable.” The gothic music video for his single “21st Century Vampire” is reminiscent of My Chemical Romance’s videos from the 2000s. Last month, he released a soul-baring track about his relationship with TikTok’s biggest star, Charli D’Amelio, called “America’s Sweetheart.” It opens with the line: “I feel so alone in a crowded room.”

Hossler—who signed to Travis Barker’s label DTA last year and will accompany Machine Gun Kelly on tour in 2022—is equally transparent about sensitive subjects in his music. “Rock is coming back because authenticity is coming back,” Hossler told me. “I love rap music and hip hop, but I have a hard time singing about bitches and money all of the time. It gets old after a while. Where’s the struggle?”

In January, Lindemann, a former pop star (who also made an appearance in Downfalls High), reinvented herself with the release of Paranoia, an EP inspired by the women of 2000s rock, like Avril Lavigne, Evanescence and Paramore. “That’s actually my favorite time in music, but I felt like I had to hide that side of myself in order to fit this pop princess vibe,” she said. “This new generation has been raised with the knowledge that mental health matters and that words hurt.” The collection of tracks, which rather aptly speaks to the anxieties and traumas of the past year, explore her neuroses. On “Loner” she sings, “I’m a loner/and I like it that way/ I like a dark room, with nobody but pain” and narrates her PTSD and night terrors in “Knife Under My Pillow.” Beyond finally feeling capable of showing what she feels are her true colors as an artist, Lindemann says one of the biggest benefits of the genre switch is support from fellow artists. “It doesn’t ever really feel like competition, it feels like friendship,” Lindemann said.

Intergenerational collaboration is proving a hallmark of this new wave, with artists popular in the early 2000s stepping in as producers or seeing resurgences of their own. This year, Fall Out Boy released a song with hyperpop group 100gecs, MOD SUN dropped a single called “Flames” with Avril Lavigne, and Jeris Johnson partnered with Papa Roach to recreate “Last Resort.” The Madden Brothers of Good Charlotte have also taken on younger pop punk bands, like Waterparks. We’re also seeing popular artists from the 2000s capitalize on a more welcoming climate for their sounds. Evanescence, AFI and 3Oh!3 have recently put out new singles and albums. “I’m glad people are shifting more toward our musical direction,” said Awsten Knight, the lead singer of Waterparks. The band, which has been making pop-punk since 2012, saw an increase in monthly Spotify listeners from 800,000 to 2.3 million during the pandemic, despite being largely inactive online for the majority of 2020. “Although saying a particular artist is bringing [rock] back does feel kind of like a slight. People have been doing this, regardless of what’s at the forefront of culture.”

So will Gen Z’s obsession with emo persist into brighter, post-pandemic days? All of the artists I spoke to responded with a resounding yes. “This resurgence in rock music is [going to be] amplified by people's craving for live shows,” Gaskarth said. “This is going to be an opportunity for artists to truly step up their game and shine.” All Time Low, who are enjoying their first major radio crossover moment this year with the hit song “Monsters,” are, like so many other rock artists who have exploded in the last year, patiently awaiting the opportunity to avenge the spirit of the music on tour. Tom Mullen, who started the podcast Washed Up Emo in 2011 to highlight the genre’s pioneers from the 80s and 90s and combat some of the negative stereotypes associated with it, told me the true essence of the genre is not, in fact, the alienation and sadness that comes through in the lyrics, but rather the joy of togetherness at shows: “[Emo] is about community and the feeling of connection with other people, and having the gumption to make music and not worry about repercussions, or who likes it.” Those who suspect Emo may not endure need look no further than TikTok to be reminded that, for true fans of the genre, this isn't a phase. It’s a lifestyle.