Lagos is a major, central location in Nigeria—but it’s also a beguiling character. The city, overflowing with people from within and outside Nigeria and considered the country’s foremost cultural hub, has remained a source of inspiration for many creatives. And while some attempt to capture its energy through writing or in films, making it an essential part of their storytelling, the Nigerian photographer, stylist, and director Daniel Obasi considers the multilayered body of the city through his photographic work.

In “Beautiful Resistance,” his debut photo book created in collaboration with Louis Vuitton as part of its Fashion Eye Series, Obasi explores and observes Lagos in its rawest state: a place where historic and political movements like the #EndSARS protests have occurred; or as a religious epicenter filled with otherworldly elements that inform the experiences of those people inhabiting the city. However, the most striking angle Obasi explores in this book is the place of queer Nigerians in Lagos—and what that might look like in an imagined utopian future.

“Lagos curates an experience that is unique to you,” Obasi tells me on a warm Wednesday afternoon. “Your experience of Lagos and my experience of Lagos are two different things. For me, it’s not even the scenery that attracts people to Lagos, but people are so tied to this city.” The photographer and I are sitting across from each other in his bedroom—the quietest place in his spacious Lagos apartment, a rare gem in a city whose architecture is known for pinched rooms in glossy buildings. From the window, the Lagos Lagoon is visible, stretching out to resemble a calm, gray floor.

Obasi began to work on “Beautiful Resistance” at the beginning of 2020. Although the initial tone of the project was meant to be somewhat journalistic, Obasi ultimately decided to create intentional images alongside candid shots of the people, places, and elements that define Lagos. “I wanted to be more surreal or metaphorical with the images I put together,” he says, “and because I had so much I wanted to say at that time with images, it just made sense to use the book and the city as the canvas to do that.”

In one of the metaphorical shots, a person painted gold, their face half-shielded by a shining, moon-like mask and wielding a cutlass, stands in the middle of a gathering filled with older-looking people wearing traditional attires. “In that particular image, I was thinking about where people were in very traditional setups,” Obasi says. “You could use it as a metaphor for meetings with elders where they all sit down and make these very damning decisions around the fate of young people without including young people in it.” In another image exploring the imagined queer futures, a man wearing wings on his back—his pants sagging so low that his briefs with the word Barbie scribbled across can be seen—skates while holding a flag and wearing an emperor’s helmet. This figure represents trade culture (men who have casual sex with other men but do not explicitly identify as gay) protecting queerness, Obasi explains—an especially daring projection, knowing that trade culture exists out of a need to maintain anonymity from any public affiliations with queer identity.

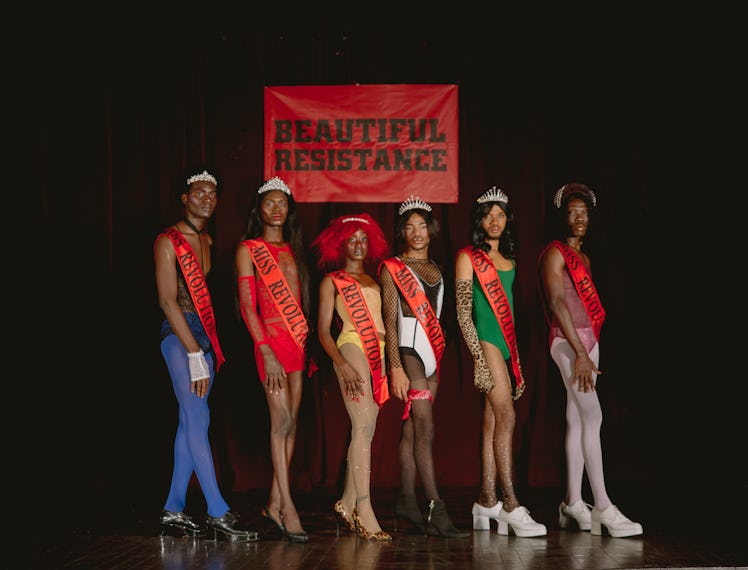

Courtesy of Daniel Obasi

While working on this book, Obasi drew substantial inspiration from those #EndSARS protests that took place in October 2020. The movement saw young Nigerians marching across the country in protests against rising cases of police brutality. But a perplexing phenomenon Obasi explores in “Beautiful Resistance” is the marginalization queer Nigerians experienced at the demonstrations, including harassment, verbal abuse, and threats from their fellow country people, with whom they were marching in solidarity. Protesters considered the experiences queer Nigerians faced at the hands of the police an unnecessary distraction that needed to be squashed.

Ultimately, in “Beautiful Resistance,” Obasi aims to tell a true and unburnished story of Lagos. “I think the city is beautiful, but there are things in the city that have not always agreed with me,” he says. “And trying to navigate all of that became much more real during the #EndSARS protests, when queer people were being asked to leave the protest ground. It just became more real, like, this is actually my life. This is actually where I live. This is a huge part of who I am, or a huge part of what I have become—and what I will become.”