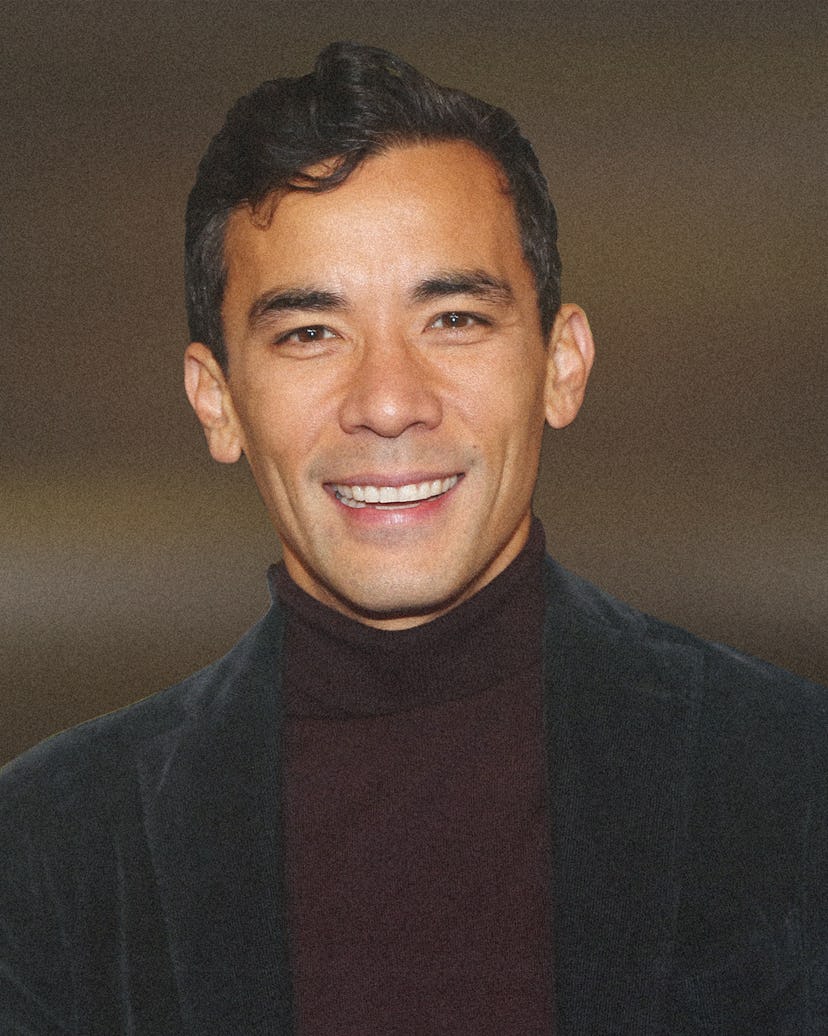

When Conrad Ricamora received the audition for Fire Island, the groundbreaking gay rom-com set on an island off the south shore of Long Island, the actor thought producers had made a mistake.

“Honestly, I was surprised they wanted another Asian American man for the male lead, which is sad, but that’s been my experience,” Ricamora tells W over Zoom a couple of days before wrapping his four-month run as Seymour in the off-Broadway revival of Little Shop of Horrors. “Usually, there’s [only] one in the movie. But they were like, ‘No, we want you to audition for this.’”

Written by Joel Kim Booster and inspired by Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Fire Island follows two best friends, Noah (Booster) and Howie (Bowen Yang), who flock to the gay haven every summer with their friends: Luke (Matt Rogers), Keegan (Tomás Matos) and Max (Torian Miller). But after learning their friend, Erin (Margaret Cho), is planning to sell the place they consider a second home, the friends are forced to make the most of what could be their last summer together on the island. While helping Howie make a move on an endearing pediatrician named Charlie (James Scully), Noah develops feelings for Charlie’s best friend, Will (Ricamora, as a reimagined Mr. Darcy), whose wealthy social circle looks down on Noah, Howie, and their eccentric group of friends.

“I remember we brought [Conrad] in for a chemistry read with Joel, and he was the only actor to fluster Joel,” says Andrew Ahn, the director of Fire Island. “There was this power play that really felt like Lizzie and Darcy in Pride and Prejudice, and very quickly we knew he was the right one. I loved how Conrad, as an actor, is pulling something off that is almost impossible, which is that you have to get audiences to hate you at the beginning and then 100 percent love you by the end.”

“It was very easy to fall in love with Conrad every day,” adds Booster. “I think it’s a huge indictment on this industry that this is the first time Conrad Ricamora is playing a romantic lead, because he’s so good at it, and it’s effortless and natural to him that I hope this is the launching pad for him to be the next Matthew McConaughey. Why the fuck not?”

Being cast in Fire Island, which centers the lived experiences of queer Asian Americans, was an all-time career highlight for Ricamora, who didn’t always aspire to become an actor or take pride in the many intersections of his identity. Born in Santa Maria, California, Ricamora moved frequently with his Filipino-born father, who was in the Air Force, and his stepmother before settling in the predominantly white town of Niceville, Florida, where he channeled his frustrations about being bullied for his ethnicity into becoming a high-level tennis player. “I love that you have to figure it all out on your own: there are no substitutions, there’s no coaching while you’re playing the match,” says Ricamora, who dreamed of winning Grand Slams of his own while in college.

Still, the actor had a range of other interests: he majored in psychology at Queens University of Charlotte, North Carolina, which he attended on a tennis scholarship, and, during his junior year, took an acting class where he was assigned a monologue from Lanford Wilson’s “Lemon Sky,” about a young man looking to connect with his estranged father. The “electricity” he felt when he performed that monologue—which struck a chord with his own feelings about his mother, who left his father when Ricamora was seven months old—is something he has been chasing for the better part of the last two decades.

That feeling kept nagging at him, even on the court. In 2001, Ricamora played a low-level professional tennis tournament in North Carolina, where he remembers feeling “super lonely” after playing on his college team for years. During that tournament, “I just felt like there was a whole other part of myself that I wasn’t living, so I decided to quit and sleep on my friend’s couch in Atlanta,” he recalls. Ricamora got a job waiting tables—and kept thinking about that acting class.

“I started doing local community theater—and then it started paying,” he says. “It was a natural progression: there wasn’t a day when I was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to be an actor now!’ I just started doing it again because I remembered I really loved doing it.”

After playing a number of theater roles, Ricamora made his television debut in 2014 on the Viola Davis-starring legal drama How to Get Away With Murder. Pete Nowalk, the show’s creator, immediately recognized the chemistry that Ricamora shared with costar Jack Falahee, upgrading the former to a recurring role for the first two seasons and then a series regular for the final four.

The show’s success, paired with his nuanced portrayal of one of the few openly gay, HIV+ and Asian American men on network television at the time, propelled Ricamora to stardom. “I was able to provide that [representation] for people that are like me—in a small town in rural Florida, feeling like I was the only Asian, gay person in the world,” he says. “All of the representation that I was able to provide just because my face was onscreen is something that was not there at all when I was growing up.”

But at the same time, the popularity of the show “changed the fact that I couldn’t get on the subway without people staring. The first three years of it were really awkward,” Ricamora says with a laugh. “Learning how to navigate people coming up to you on the street after living your whole life just being able to breeze by, I had a little bit of social anxiety. Then it became normal.”

How so? “I think it was from playing tennis and my psych degree that I learned to not worry about things that I can’t control. I would show up to work and then I’d live my life,” he responds. “[I’m] still the same person.”

While he had never visited Fire Island, Ricamora, who was a big fan of Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice, could tell that Booster’s script had the right balance of real-life heart and humor with a distinctive focus on the queer Asian American experience. “It’s something that I loved about comedies like Bridesmaids—comedies that are hilarious, but still have integrity and have a strong heart,” he says.

Fire Island doesn’t shy away from the issues of race and class that can arise in a queer mecca like the Pines, which can be both liberating and, as Booster has put it, “oppressively white and inherently classist” at the same time. In fact, it’s a central theme of the plot. “People who have white skin and wider eyes can come over to this country and people are like, ‘Oh, you’re American.’ But for some reason, Asian Americans—even if we’re [the] second-, third-generation—we are still thought of as ‘other,’ as if we’re not Americans,” Ricamora adds. “And I think one of the reasons it’s important that our stories get told is that we can show—not just for ourselves, but for other people: ‘Hey, we live here, we’ve been here for a long time, we’re not going anywhere.’ And I think that it’s important for [Asian men] to see ourselves as sexual beings, because it’s so detrimental when you are continually shown to be the butt of the joke.”

But the film also honors the importance of queer friendships and chosen families—a sentiment shared by the director and principal cast, who stayed in a house together during the two weeks they shot on the island. “My number-one hope is that people are entertained and feel that sense of community we felt while we were making it,” Ricamora says. “Everyone has a seat at the table and you can be your authentic self.”

Ricamora is also willing to create his own seat at the table. He and his best friends, Kelvin Moon Loh and Jeigh Madjus, have spent several years developing “No Rice,” a half-hour comedy series based on their own real-life experiences as gay Asian American men in New York City.

“So much of our stories from the past have necessarily been telling the trauma that we’ve had to endure and still have had to endure—and it’s important to not forget their stories,” Ricamora says. “But it’s important to also celebrate the joy of being in the queer community, because there is so much joy, there is so much that is so beautiful and fabulous and exciting and sexy about it. In the midst of all of those stories being told, it’s important for us to celebrate as well. Otherwise, what are we fighting for?”