Charlie Engman and His Mother Kathleen Discuss the Photographer’s New Book, Mom

The photographer and the muse are tied in more ways than one, and have a tome coming out that documents the subtleties of their relationship.

Charlie Engman is an artist making things with the person who made him. I mean this in a literal sense: the photographer is creating work with his own mother, Kathleen. For the last 10 years, Engman, the photographer, and his mother, the muse, have collaborated on a number of photo shoots that have caught the world’s attention, leading to global recognition in the fine art and fashion industries. After exhibitions in China, fashion campaigns for brands like Collina Strada, and fashion magazine editorials, Engman is releasing his first book, appropriately titled, MOM. I FaceTimed Charlie and Kathleen to discuss the evolution of their relationship, art, and their new book, in celebration of Mother’s Day.

In art school there’s always this talk about the difference between taking a picture versus making a picture. Taking a picture is, for example, showing up at a party and documenting it. You don’t really know what will happen at the party, but you’re there to react to whatever does happen with a shutter. Making pictures means having a clear idea of what you think you want, assembling a variety of variables (subjects, set design, etc.) and then trying to realize that vision. I think that when you are approaching your mom in this book, it’s clear to me that these pictures are made. At the same time, this book is also about this collaboration or relationship between you and one of your variables: your mother.

Charlie: Even the language that we use there is really interesting. This idea of taking something versus making something. In the interviews my mother and I have done before, I often characterize photography as a territorial process, where you’re trying to stake some ownership over an idea of reality or context that you are finding yourself in. That’s actually just baked into the photographic process—to actually have that, for lack of a better word, colonial aspect. Where are the ethics within that, or can you inject that accumulative process, where you really are using this verb “take”? Can you invert that and make it into a somewhat more generative process where you might use the word “make”? One is accumulative, and the other one is more generative. To me, the idea of making something doesn’t have a lot to do with whether you put together the elements, whether it’s in a studio and you have to supply all the elements yourself, or whether you’re on the street and you happen to find something in front of you with your camera. All photography is constructed in a sense, because you are choosing how you mediate whatever thing you find in front of you that you end up photographing.

This is an issue we have in photography: can you ever really do anything ethically in photography? And is the photographer the only person who has to bear the weight of that question? Especially when images are being made, not taken, you’d have to poll the whole team to really know the truth. Does the subject feel okay about what was made? The hair team? Makeup?

Charlie: Did you have something you wanted to say, mom?

Kathleen: What you just said made me think of something. All these years, I’ve learned so much from you, and I suddenly have a picture of the weekend that we did the green screen video for the exhibition in Toronto two years ago. When I look at the video footage, I think, “How did I do that?” It was because of what you just said. I didn’t inhabit, I didn’t perform something, some person. It was the making. I don’t know a lot of people who do this for a living. I don’t do this for a living, so I don’t know how people talk about this.

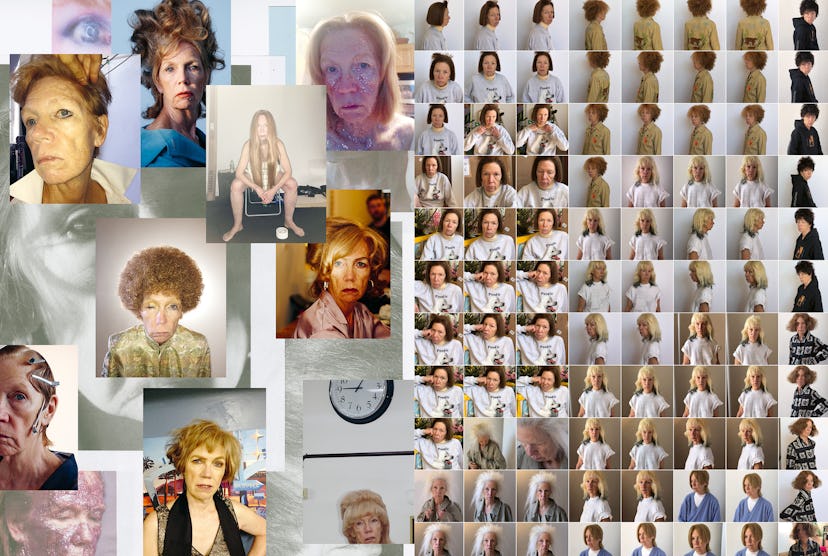

Photograph from Charlie Engman’s new book, Mom, published by Patrick Frey Edition.

Photograph from Charlie Engman’s new book, Mom, published by Patrick Frey Edition.

I don’t pose for photographs the way you do, Kathleen, but I do take a lot of my own pictures. People who don’t work in this field don’t always realize how cathartic it is for a model, or subject, to perform a character or to help translate someone’s vision. What has it been like making pictures with your son in this way for 10 plus years? I typically think of the mother and son relationship as one where the mother exists above her son, but the relationship between a photographer and subject is usually more democratic. What is it like to have that relationship change when making work together?

Kathleen: I hear you speaking about and working through your own relationship with the idea of mother or mom in that question. This book is special. Not everybody has a book for Mother’s Day. But I have to say, the more that I live with this, the more powerfully it occurs to me that this changed my life. The paradox is learning to say yes. And then just try it! It’s about discovering what it feels like to trust.

That’s a testament to the power of this body of work. I can’t help but question the mother and son relationship at large, or think about my own. Do a lot of people come up to you, during interviews and whatnot, and project their relationship with their mother onto you, because of this body of work?

Kathleen: The short answer? Yes. But if you want an anecdote, I’ll give you a longer answer. When I was in Toronto, where we first debuted this body of work at Scrap Metal Gallery, we had all this work on the walls and the feedback had been, “Holy shit.” When the exhibit was coming to an end, I went back to Toronto to break the show and get it back into a van and drive it to New York. A 30-something, 40-something couple comes up to me. The man says, “You saved my marriage,” and the woman starts to weep. Then she’s like, “Come on, tell her.” The guy says, “I can’t even remember how many times we’ve been in the show. All these women in this space. I finally can actually be with them, and I don’t have to ask them to explain themselves. I get that people have really strong feelings and they can just have them, and that if I’m patient I don’t need to make her tell me. She’s actually already trying to tell me.” I will never forget this.

Charlie: It’s interesting because we had another exhibition of the work in China recently, in November. One of the questions that we had from a woman in the Chinese audience ask my mom, “If I do what you are doing, will I be happy?” Which I just thought was such an interesting question to receive.

Photograph from Charlie Engman’s new book, Mom, published by Patrick Frey Edition.

Photograph from Charlie Engman’s new book, Mom, published by Patrick Frey Edition.

Charlie, I have a question for you. At the start of this series, I spoke with the photographer Molly Matalon. We talked about this idea of photographers contributing to a body of work and then eventually publishing that body of work in book form. It can be difficult to choose when to do that, especially if the content will look similar in future works. If you’re going to continue taking pictures of your mom, how do you decide to stop and release a book during that process? This is also my way of asking, will you continue to take pictures of your mom now that this book, over ten years in the making, is finally out?

Charlie: From my perspective, this sounds a little bit like buying into this myth of photography as something that can unground the ultimate truth surrounding a subject. The more I make photos and the more I try to arrange them and see how they interact with each other, the more it becomes clear that everything is very much situated in its own time and place. I made this work in the second decade of the 2000’s, mostly from 2010 until now, and that’s visible in the work. That doesn’t mean that the work doesn’t have a timeless quality, but the value is attached to those kinds of very specific things. It’s important for me to lean into that, rather than trying to minimize things so they could exist at any time, in any place, or under any context. It’s about creating a balance between making work that’s grounded, but also expansive. Which is why having a subject that is very specific, like my mom, is a beautiful opportunity. We can take something that is concrete, like the relationship we have, and we can pull out as much as we possibly can with the context of our relationship.

Kathleen: We’ve done so many interviews, and a recurring motif is this idea of context specificity.

Charlie: Right, I’m obsessed with this idea. For me to have made the images that exist in the book is pretty important because the relationship between images is much more interesting than each image alone. I was trying to realize what the ethics revolving around the representation of this person that I care about are. What is the image-making process doing for our relationship? And then, by extension, what is that doing for the viewer, the third party? I’m actually really uninterested going forward, at least for the time being, in continuing that exact process, which in one sense is actually a very internal, very sort of navel-gazing, type of process. When you look through the book, it’s just my mother over and over. The fact is actually that she exists in a much broader context, too. There’s a part of the work that has been solved by the book, and going forward it feels much more valuable to look at what the work does now that it’s been externalized, and it’s kind of forced my mom into the public realm in this way.

Michael: Right, so now it’s looking at the result of this book-making or photo-making process, which becomes its own process.

Photograph from Charlie Engman’s new book, Mom, published by Patrick Frey Edition.

Photograph from Charlie Engman’s new book, Mom, published by Patrick Frey Edition.

When you two go abroad to Toronto or China, do you feel this pressure to be ambassadors of the work?

Kathleen: We actually don’t hang out in real life (laughs).

Charlie: What are you saying? Of course we hang out. This is something that is very important to me, actually. When people interview me about the work, they always ask subjective questions about my mom, like how does she feel, or what was her experience? Well, I don’t know. I can’t answer. It’s not appropriate. It’s actually unethical for me to decide what she feels about the project. It’s incumbent upon me to give a platform of authority to my mom in this example, so that she can have a voice outside of the image.

Kathleen: What I said earlier about that couple in Toronto, neither Charlie nor myself was in the room when that man felt his marriage was saved. It was just the man, his wife, and the work. So of course the work is doing a lot of the work itself.

Charlie: Right, but what I’m saying is that it’s important to me, going forward, that when the work is being discussed, or we’re having these kinds of situations, to bring you into these conversations.

Kathleen: I appreciate that, and that is one of the reasons you’re so good at what you do. I mean, I’m sorry. Charlie’s just like, “Oh, that’s just mother talk.” But he’s wonderful.

Photograph from Charlie Engman’s new book, Mom, published by Patrick Frey Edition.

Related: Campbell Addy on Shooting Kendall Jenner and Megan Thee Stallion Before the Pandemic