“There is no Filipino art history,” one of the artist Carlos Villa’s professors at the San Francisco Art Institute told him in 1961. Whether that professor meant to sound dismissive or not, the tough reality was that, to an extent, it was true—especially when it came to Filipino-American art of the era. But hearing these words became a catalyst to change the route of Villa’s artistic manifesto, inspiring within him a deep desire to search for cultural truths. And now, Villa's art—from his paintings and drawings to sculptures and performance pieces—finally gets the recognition it deserves at the Newark Museum of Art, where a solo retrospective, a first for the Filipino American artist, has opened.

Titled Carlos Villa: Worlds in Collision the exhibition, produced by curators Trisha Lagaso Goldberg; Mark D. Johnson; and Newark senior curator of American Art, Tricia Bloom, demonstrates the need to fill a notable gap in art history, while also rejecting non-Western art being shown through a Western lens. The show opens with the first of three grand capes, which are nothing like the royal wares depicted in traditional English or French renderings of their respective monarchies. Instead of red velvet and typically Western styles, the capes resemble large moth wings adorned with all sorts of materials: feathers, swirling acrylic paint, and even chicken bones. “[Villa] made dress critical to his work to form a connection with oceanic cultures,” Lagaso Goldberg, the exhibition's chair and co-curator, tells W. “But he himself also thought of clothing seriously. He often dressed meticulously and presented himself super professionally.”

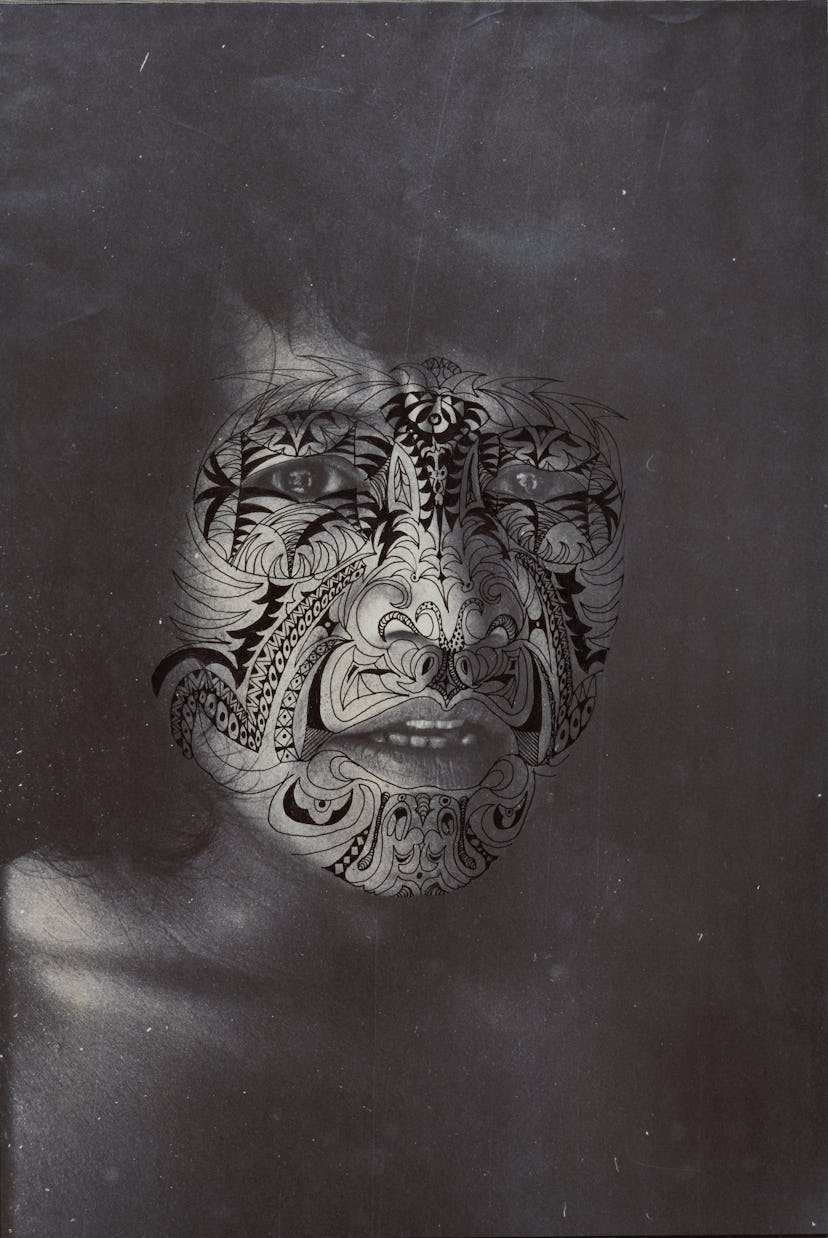

There are two other variations of capes hanging in the center of the exhibition space that command respect and attention: a self-portrait with oceanic-inspired tattoos inked onto Villa's body and face; his early modern paintings of multicolored coils, and even a video of himself partaking in a ritualistic dance. In another room, viewers can immerse themselves in the social activism and community-building at the forefront of Villa’s life during the ’70s. In 1976, the artist organized a curatorial project titled Other Sources: An American Essay, which exhibited women and artists of color, including modernist sculptor Ruth Asawa, Native American artist Frank Day, queer abstract artist Bernice Bing, and Nicaraguan painter Rolando Castellón. Winding down the exhibition is a set of paintings on the other side of the space. Here sits a collection of muted paintings created during the latter part of the artist's life.

While the works boast a high level of beauty, a closer look into the retrospective tells a story of a Filipino artist through several pivotal chapters of his life: from finding his footing in the world as a young artist to someone experiencing a racial awakening to a social activist fighting for marginalized artists of all sorts. “The setup of the exhibition is very deliberate,” says Tricia Bloom. “Viewers are meant to see the different stages of his life both artistically and personally, as a story.”

Carlos Villa’s artistic career began in 1961, when he started to work as an abstract artist in New York City. At the time, he subsidized his paycheck with a bartending gig at New York City's Ninth Circle, a steakhouse in the West Village frequented by Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Charles Mingus, which closed in 2002. “He did art as a form of relaxation, actually,” co-curator Johnson, who was also close friends with Villa, tells W. “But his work shifted with the increasing civil rights movements for greater awareness of diversity, political engagement, and cultural engagement happening in the country." Villa rallied for fair Filipino immigration laws in 1965 and supported the Black Panthers of ’66, in addition to Native American activists occupying Alcatraz Island in ’69. “He moved back to San Francisco in 1969 because it was such a hotbed for these movements,” Johnson adds.

At that point, Villa began to fill in the blanks when it came to Filipino-American art history through his work. “Carlos looked for lineage and ancestry, even though no one came before him. How does one begin this process when there is no one that comes before you?,” Goldberg asks. Working as an ethnographer, Carlos sought inspiration from not just the Philippines, but other pacific regions like Hawaii and New Zealand. “If you take a look at his work, it drastically shifts. He decided to change his practice to what he called ‘Third World Liberation’ which essentially means to free his art from post-colonial perspectives,” Johnson adds. According to Johnson, contemporary art answered all the questions Villa had in life except for one: “Where is the Filipino?”

In today’s world, inclusion and diversity are key topics across cultures, industries, disciplines, and communities. In this way, Villa was ahead of his time. “His work has been overlooked and underrecognized because it didn’t look like his colleagues',” Goldberg says. “He broke the model of merging aesthetics, lineages, and histories, [which]hadn’t been present before. He could’ve had commercial success—in fact, in 1971, the Whitney Museum purchased a work made by him—but he chose to uplift communities and smaller institutions that aligned with his vision.”

A look inside Carlos Villa: Worlds in Collision at the Newark Museum of Art.

Now, his legacy forges on. To those viewing the exhibition in Newark, Carlos Villa’s work is a tale of forging a history that was arguably nonexistent before. Because of him, many Filipino-American artists will have a point of reference for history—and an artist to look to when considering their own identities in the art world.

Those who knew Villa personally recognize how impactful of an artist he was. “He spoke like a beat poet—often in abstraction,” Goldberg says. “You never interrupt a poet when they go off, so we were left conversing among ourselves to understand after.” As the Filipino-American artist is exhibited for the first time in a retrospective at a major museum, it's clear the phrase “There is no Filipino art history” no longer holds weight.

Carlos Villa: Worlds in Collision is on view at the Newark Museum until May 8th, 2022, and will then be transferred to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco from June 17th and the San Francisco Art Institute on September 21.