Benedict Cumberbatch Never Thought He’d Be a Leading Man

With The Power of the Dog, the actor hopes to spark conversations around strength and masculinity.

It’s hard to imagine that the Oscar-nominated actor Benedict Cumberbatch never envisioned himself as a leading man. But this year, he takes awards season by storm with not one, but two major roles: the cranky, borderline abusive rancher Phil Burbank in Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, and the schizophrenic, feline-obsessed artist Louis Wain in Will Sharpe’s The Electrical Life of Louis Wain. The films couldn’t be more different from each other, but Cumberbatch’s electrifying performances in both are arresting and unforgettable. In W’s annual Best Performances issue, the actor talks about learning to pluck the banjo and hand-roll cigarettes in the New Zealand mountains, and explains why he never wants to work with cats again.

In Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, you play Phil Burbank, a rancher who has very intense feelings about his brother. But in real life, you are an only child. Did that inform your performance at all?

It's very weird, not having had a brother, to manifest that, but at the same time, the dynamic of their relationship is so specifically about two diametrically opposed human beings who are lumped together, and it's an odd-couple friendship relationship. The filial part of it was something that had to be filled in. Jane was brilliant. She had us do crazy exercises of proximity, like waltzing together so that we could hold each other, smell each other, be very close to each other's bodies as we would've done in a very visceral way as brothers for all of our lives. And these are two men who slept in the same room, until [Phil’s brother] George finds love and goes next door to the parents' bedroom with Rose. It's very Freudian. You'd want Jesse [Plemons] as a brother. Phil's a mean bitch to him; he's just vile.

What’s your favorite part of the film?

One of my favorite moments in the whole film is when George (Jesse Plemons) and Rose (Kirsten Dunst) are waltzing at a picnic spot that Rose chooses after their wedding. He breaks away to hide his emotions, because he's overwhelmed by the idea that he doesn't have to be alone anymore. Just saying it makes me well up; it's just so touching. It's part of the tragedy—Phil's looking for love, he's looking for companionship and understanding, and he doesn't get it anywhere, so he ends up hating everything. He's not allowed the love that he experienced early in his life. Societally, he can't fully express himself, and therefore he takes it out on the world. He's just twisted into a kind of pretzel of hate and fear and bitterness by that, so it's a shame.

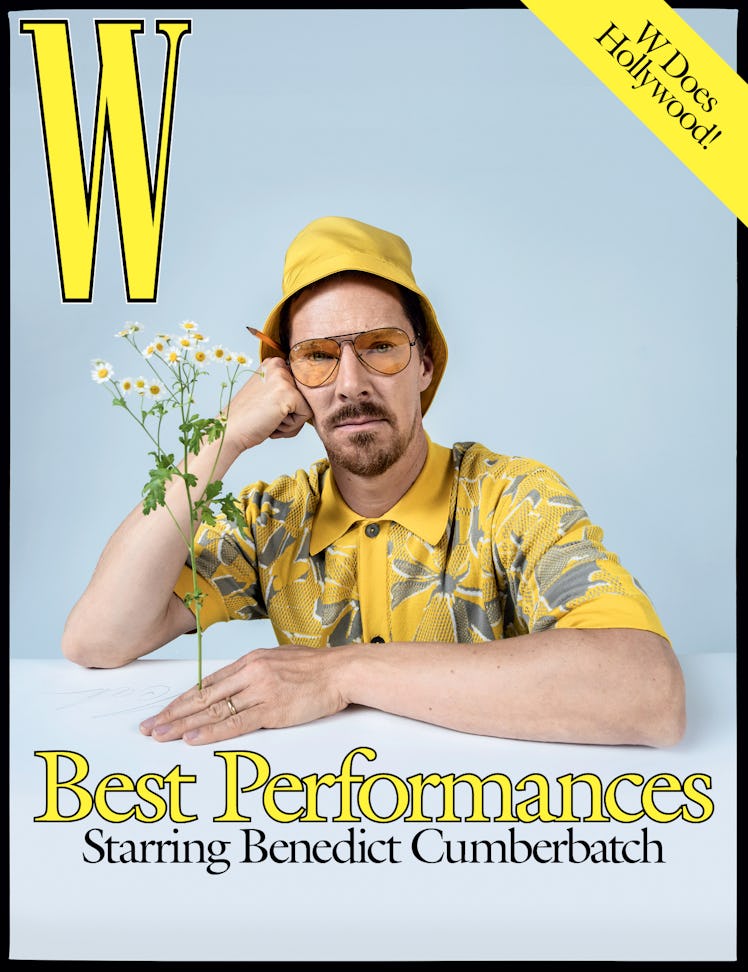

Benedict Cumberbatch wears an Hermès shirt; Ray-Ban sunglasses; stylist’s own hat.

How did you get involved in the film?

I heard that Jane Campion wanted to meet. I heard what the project was called. I read the book, I read the script, and then I met her. I was always going to say yes, no matter what the ask was, to be frank. I just think she's truly a living icon, an extraordinary filmmaker, and I was less concerned or aware that it was her first film in 11 years or her first male protagonist. That didn't matter to me. I just wanted to work with her.

What was it like being the first male protagonist in Jane Campion’s oeuvre?

I think it's so important that she's the one who tells this story. It started in that first conversation, the sensuality she wanted to crack open in this very macho, toxic masculine world. The layers of delicacy to this complex character that she wanted to reveal. How she wanted to do that, how she wanted to signify it as a very visually orientated, sensually oriented filmmaker, through her lens and her idea of that era and what subverts type and stereotype, and archetype most importantly, was fascinating. I thought, This is a very interesting take on that world, that genre, and queer in its perspective in every regard. I love that. I think I was drawn to the duplicity of the character: somebody who's completely drunk on his own masculinity, to the point that it blinds him to love or to the potential of kindness, because of how far he is from his one taste of that forbidden fruit. And the tragedy of a man who's living his life without being able to love or be loved really pulled me into Phil's world.

Did Jane make you watch any other Westerns? Are you a fan of that genre?

No, but they're great. From John Wayne and John Ford to the revisionist Westerns from Clint Eastwood. The Power of the Dog [as a Western] is closer to There Will Be Blood. It's about a period of transition. It's about a move from a more analog, animal, manpower-driven era into mechanization. There’s a man who can't let go of what was and wants to celebrate that, and a brother who's moving toward a love in an automobile that just separates exactly what was going on in that era. So that is against the backdrop of a Western, the whole thing of landscape being another character, whether it's alienating and terrifying, the house being somewhere that's almost haunted. For my character, Phil, the landscape is everything that gives him solace, purpose, control, as well as privacy and freedom to remember who he was and perhaps still is, although he doesn't allow himself to be it.

How did you train yourself to ride horses and wrangle cattle and make it look like you’ve been doing it your whole life?

I think it was integral to convince and authenticate how lived an experience it was for him to do that, to manage the animals, the men, the land, the weather, the braiding, the cigarette rolling, the whittling. I never quite mastered the one-hand cigarette rolling. It's harder than most people think. It's pretty damn hard to do it as it's described in the book; it's fine to roll a really big fat doobie that falls apart in your first take and gets in your mouth and burns a hole in your chaps. That's great, and I did that lots, for real. But he’s described as rolling rail thin, tight cigarettes. Everything about him is controlled and buttoned up, but also with great dexterity, as well as strength.

What about playing the banjo? Was that difficult to learn?

With the banjo, there's nothing like picking up an instrument for a few months and having to play it on set like you're a master of it, and just blowing any kind of moment of being focused on your authenticity or your absorption in a part. You just hear all the fakery coming back at you. I had it with Sherlock when I was playing the violin.

What’s the big takeaway from The Power of the Dog?

I think the big takeaway from this film is to understand that strength comes in very unexpected forms. We have to try and break down this very narrow definition of [strength] as the bully of the classroom having the keys to the kingdom, because that bully suffered something in order to be wanting to punch down, or be a misogynist, or belittle people, or point out flaws instead of encouraging people. It's impossible to just flick a switch, and I know it sounds a bit sappy, but we would live in a better place if we could question that behavior by understanding it and looking for it in dialogue with our children and educators and culture at large. Phil's set of circumstances are very particular to him, obviously, and looking under the bonnet of him doesn't solve toxic masculinity. He lacks love. I think that is a general truth of anyone who behaves in a way that needs brutality to control the situation—they've lacked love at some point in their life, for sure. That's when the insecurity comes out, and that's where the fear comes out, and that's where the need to dominate comes from.

In Will Sharpe’s The Electrical Life of Louis Wain, you play an artist with schizophrenia who is famous for his colorful drawings of cats. You’re having a big animal year.

Lots of animals. Cats are harder to herd than cattle, I'll tell you that much.

Louis Wain was not like Phil Burbank—he was very loving. What drew you to that film?

He's knocked around by the hardness of the world, this Victorian, stay-in-your-lane kind of status quo, this conservative society of prescribed behavior. He, now, would be a much-celebrated artist in the vein, I think, of someone like Grayson Perry. But in his day, he had to be an extraordinary hero, in a very quiet way. And that's what really drew me to him. He persisted and lasted a long time.

Can you draw?

Yeah, I was an art scholar at my school. I was quite good. I did it a lot and loved it. It's a muscle, and it's fallen out of my life drastically.

Cumberbatch wears a Levi’s Vintage Clothing jacket; Emporio Armani shirt; Stetson hat.

Had you ever drawn cats?

No, never Louis Wain cats. But he's very helpful; he leaves instructions for us. There is a way of doing it that he describes: Always start with the ears to get the ratios right. But I think, rather like signing a signature, that kind of body integration, that hand-eye coordination, that thing of connecting with what the movement of thought process was behind creating something, even though it's mimicry, is really useful for tapping into the ghostly connection with someone who's lived and done that for real. That was very important to me, so I worked at it, for that sensation, for that communion with him. It’s a meditation.

In The Power of the Dog, Phil refuses to wash up before dinner after a day of wrangling cattle, and it causes all sorts of problems with his family.

It's the least of humanity’s problems. It might be one of [the problems], frankly, that we use so much water on a daily basis, but that's another thing. I'm not advocating doing it or not doing it, just be clear about that. But it was very interesting to experiment in the 21st century with not doing it, way before this whole celebrity conversation apparently started up about washing or not washing.

Do you think Louis Wain bathed less than we do now?

I think he went through a phase of depression in the less manic stages of his mental health issues, where he was living pretty much in squalor, with his cats and everything that they can leave behind. He had a hell of a lot of cats at one point.

Do you have cats?

No, I've had my grandmother's and friend's, but never my own. I was an only child who went to boarding school.

No fish? No pets of any kind?

It's time to start playing the smallest violin in the world for me right now. I was very lucky because I had other people's pets. I was like an uncle or godparent. You get all the benefits without any of the trauma. We had animals at school that we tended to, I don't know how they survived. I didn't go through the trauma of seeing them as babies and then going through their life cycle with them and the inevitable end. I love, love, love, love, love dogs. Cats, on the other hand... Don't ever do a film with them. They just wander around looking really unimpressed with everything. I love them, but working with them is really tough.

Both of your parents are actors. Did they ever discourage you from this profession?

They discouraged it, of course they did. They were old enough when they'd had me to know that it was a ridiculous choice of occupation.

So when did you tell them that this is what you wanted to do?

Well, there was a moment in a car park, I must have been in my early twenties; I was at university. I played Antonio Salieri in Amadeus, and I came out and said goodnight to them, and Dad got ahold of me by the shoulder and went, "Look, you are better at this now than I ever was or ever will be." Half of the reason I'm doing it is just to go, "It's going to be all right. I'm really enjoying this, and here's my work." I'm thrilled to show it to them and share it with them.

When did you know acting is what you wanted to do?

I got bitten very early when I saw my mum perform. I wasn't a child actor, I'm happy about that. Nothing against people like my good cast members who have been, but I'm happy I had the experience I had. I sometimes in my twenties thought, Damn, I wish I could have started earlier, because I was never going to be playing a leading man. I look the way I look. Maybe I'm growing into my looks now. I went from playing women to men in an all-boys boarding school within the space of a year. I think I was Rosalind one year, and then a year and a half later I played Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman.

Do you ever get starstruck?

All the time. I was starstruck by Gary Oldman when I first met him, and he sort of looked at me like a photographer. Nigel Godrich came to watch me in Hamlet, and I was a bit starstruck by him. Thom Yorke came one night, and I was terrible. It was like a high school prom, where I couldn't pluck up the courage to give him a kiss.

Hair by Ali Pirzadeh for Dyson Hair at CLM; makeup by Daniel Sallstrom for Chanel at MA+ Group; manicure by Michelle Saunders for Nailtopia. Set Design by Gary Card at Streeters. Produced by Wes Olson and Hannah Murphy at Connect the Dots; production manager: Zack Higginbottom at Connect the Dots; photo assistants: Antonio Perricone, Jeff Gros, Morgan Pierre; digital technician: Michael Preman; lighting technician: Keith Coleman; key grip: Scott Froschauer; retouching: Graeme Bulcraig at Touch Digital; senior style editor: Allia Alliata di Montereale; senior fashion market editor: Jenna Wojciechowski; fashion assistants: Julia McClatchy, Antonio Soto, Nycole Sariol, Sage McKee, Josephine Chumley, Rosa Schorr; production assistants: Tchad Cousins, Juan Diego Calvo, Gina York, Brandon Fried, Nico Robledo, Kein Milledge; hair assistants: Tommy Stanton, Sol Rodriquez, Andi Ojeda; makeup assistants: Tami Elsombati, Bridgett O’Donnell; manicure assistant: Pilar Lafargue; set coordinator: Sarah Hein; set assistants: Olivia Giles, Seth Powsner, King Owusu; tailors: Suzi Bezik, Cardi Mooshool Alvaji; tailor assistant: Elma Click