Is There Anything Bad Bunny Can't Do?

The Puerto Rican superstar on bringing reggaeton to the world, winning a “gringo Grammy,” and his nascent wrestling career.

The day before the Grammys, Bad Bunny could be found playing dress-up in a Hollywood studio. The Puerto Rican megastar, who had turned 27 a few days earlier, emerged from a dressing room in a tailored Celine suit. The look was Men in Black sharpness—thin black tie, crisp white lapel, sleek lines—but with some key twists. His mop of tight curls was gathered on one side of his head, and where one might have expected to see a dress shoe, he was wearing imposing furry boots—not après-ski so much as full-on yeti. Bad Bunny has been known to incorporate mouse ears and other animal motifs into his aesthetic, but the yeti boots were taking the theme to a new place. He looked a bit as if he’d been cast as a woodland creature in a futuristic, high-fashion staging of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

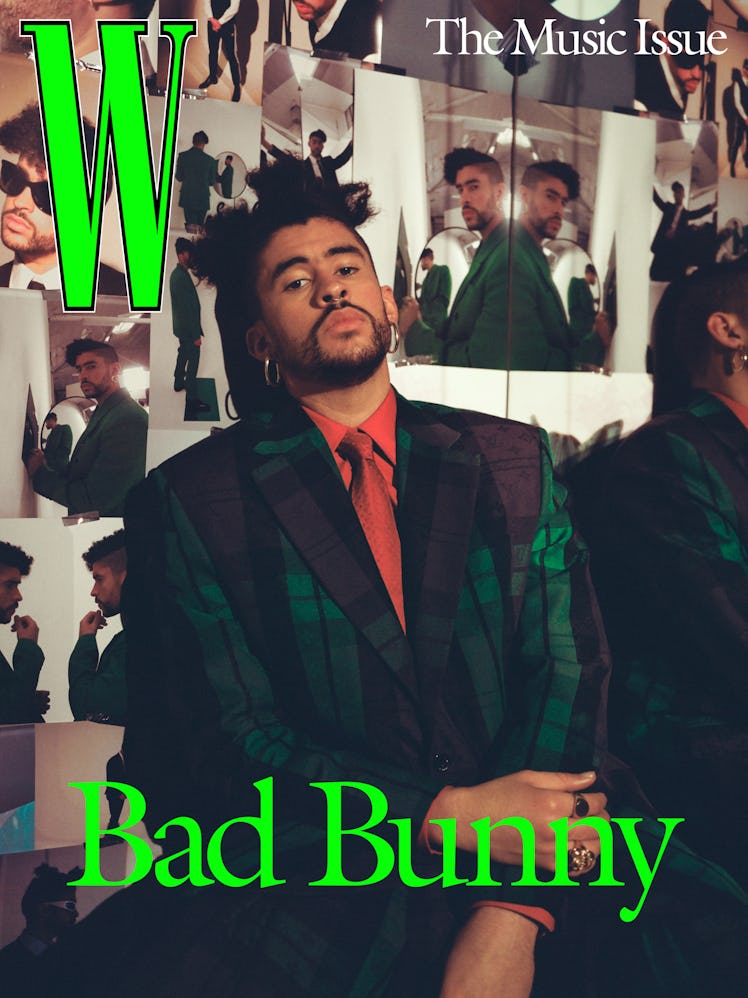

Bad Bunny’s style, like his music, is so hyper-eclectic that describing it often requires not just compound references but whole imaginary scenarios. At one point during the W photo shoot, he was wandering around in a pleated plaid skirt and matching blazer, a wide-brimmed hat, and cherry red cowboy boots—what might result if, say, a Catholic-school girl reworked her uniform into a gaucho silhouette. The artist and director Martine Syms was using a variety of cameras, both film and digital, from different eras to capture Bad Bunny as a kind of musical time-traveler. Members of her team were printing some of the images in real time and arranging them on a wall, which then became a backdrop for subsequent photos. The reflections and recursions were meant to give the portraits a “portal feeling,” Syms told me later. “I wanted to try to tap into some of the various archetypes that he taps into in his music.”

Celine Homme by Hedi Slimane jacket, shirt, pants, and tie; his own small hoop earrings and nose ring (throughout).

It was an ambitious goal. Even in our genre-bucking times, Bad Bunny is a lane-hopper of unparalleled range. He made his name as a revivalist of early reggaeton and Latin trap sounds, but did so with painted nails and feminist lyrics, upending many of the macho norms of the very genres he was referencing. In just a few short years, he’s become a global pop phenomenon and commercial force—and also a salt-of-the-earth protest singer who helped bring down a corrupt administration back home. Underneath it all, he remains a country boy from Puerto Rico’s northern coast, a laid-back beach kid who will roll into an industry party in board shorts and flip-flops. And yet, as of a few months ago, he is also a newly minted wrestling star, a smack-talking brawler who delights in smashing a guitar on the bulging lats of WWE star Mike “The Miz” Mizanin.

Celine Homme by Hedi Slimane jacket, shirt, pants, and tie; stylist’s own ring.

Bad Bunny was up for two awards at the Grammys. His collaboration with Dua Lipa, “Un Dia,” was nominated for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group, and his third album, YHLQMDLG—short for “Yo Hago Lo Que Me Da La Gana,” or “I Do Whatever I Want”—was in the running for Best Latin Pop or Urban Album. As we parted ways, I wished him luck, though I had the distinct feeling that he wouldn’t need it. The Grammys have been slow to recognize Latin music of every stripe, but Bad Bunny’s dominance had become undeniable. He was the most-streamed artist on Spotify in 2020. His latest album, El Último Tour del Mundo, released in November, is the first all-Spanish-language album to reach No. 1 on the Billboard 200 chart.

Celine Homme by Hedi Slimane jacket, shirt, pants, and tie; stylist’s own ring.

Since exploding onto North American radio and pop charts in 2018 with the smash hit “I Like It,” his boogaloo-meets-trap collaboration with Cardi B and J Balvin, Bad Bunny had taken home two Latin Grammys. Still, winning a “gringo Grammy,” as he has called it, would carry particular significance. When, as expected, Bad Bunny did win for YHLQMDLG the following night, he delivered part of his acceptance speech in Spanish. “It’s very special to be able to achieve my dreams simply by doing what I love,” he said. “That they give me an award for doing what I love—it’s like, okay, give it to me.”

A few weeks later, I spoke to Bad Bunny by phone. He was somewhere near Orlando, Florida, where he had been making weekly appearances on WWE’s Monday Night Raw. He was still basking in the glow of his Grammy win. “It was one of the more beautiful moments in my career,” he told me, “the recognition of an album that, for me, is very special, and which I consider one of the best albums in the latest era of reggaeton and the Latin genre.” When I asked if singing and speaking in Spanish was a political choice, however, he said no. “I’m simply being myself,” he said. “I think we’ve already proven that music is a universal language. You have people from all parts of the world singing songs in Spanish. We don’t have to sing in -English anymore to cross over.”

Bottega Veneta jacket, pants, and boots; Vince sweater; stylist’s own earrings and ring.

Bottega Veneta jacket, pants, and boots; Vince sweater; Marvin Douglas ring; stylist’s own earrings.

Bad Bunny was born Benito Antonio Martínez -Ocasio in Vega Baja, a rural beach town about 30 miles west of San Juan. His father was a truck driver; his mother a schoolteacher. (After Benito, they had two more boys, Bernie and Bysael.) Growing up, Benito sang in a children’s choir at church. He started freestyling in junior high, mostly to entertain his friends. From a young age, he was omnivorous in his musical interests.

“My father would usually listen to tropical music,” he told me, “a lot of salsa. My mom liked merengue and balada a lot. At my grandfather’s house, I would listen to old man’s music, like bolero, bohemia. With my friends, I would listen to a lot of reggaeton. Some would listen to rock. I have musician family members, musician friends. And so I grew up around a lot of musical preferences. Obviously, I always identified more with reggaeton, because it was popular music in my country and from my childhood and my generation. That has always been the foundation. But it’s not like I am just there. I have a lot of rhythms in my head.”

Burberry dress, shirt, pants, hat, and boots; rings: (right hand) stylist’s own, (left hand, from top) Vitaly, Joolz by Martha Calvo.

After high school, he studied communications at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo, and moonlighted as a grocery-bagger at a local supermarket. Between classes and night shifts, he began uploading self-produced songs to SoundCloud as Bad Bunny. (The name was inspired by a childhood photo of Benito dressed in a bunny suit for school, right before Easter.) One of those songs, “Diles,” a trap anthem about making sure a woman is satisfied in bed, went viral in 2016. Soon he was collaborating with música urbana veterans like Arcángel and Daddy Yankee, and eventually with Cardi B and Drake. His debut album, X 100PRE, which was released on Christmas Eve in 2018, reached No. 1 on Billboard’s Latin albums chart.

Bad Bunny’s ascent coincided with an exceptionally turbulent period in Puerto Rico, and his willingness to meet the moment has made him a kind of folk hero back home. A year after Hurricane Maria ravaged the island, he released “Estamos Bien,” about resilience during the storm’s harrowing aftermath. When he performed the song on The Tonight Show, Bad Bunny criticized the White House from the stage. “More than 3,000 people died, and Trump’s still in denial,” he said. Then, in the summer of 2019, a texting scandal and political crisis enveloped Puerto Rico’s then governor, Ricardo Rosselló. Bad Bunny cut off a tour to join demonstrations in San Juan. He also produced a protest song with Residente and iLe, “Afilando los Cuchillos,” or “Sharpening the Knives.” Last year, in another Tonight Show appearance, he performed in a T-shirt that paid tribute to a homeless transgender woman, Alexa Negrón Luciano, who had been murdered in San Juan. “They killed Alexa, not a man in a skirt,” the shirt said.

Louis Vuitton Men’s jacket, shirt, skirt, and tie; rings: (from top) Vitaly, Jewels by Dunn, his own; stylist’s own earrings.

During the pandemic, Bad Bunny released three albums. First came YHLQMDLG, a valentine to early reggaeton that, like much of his music, deploys nostalgia in a way that doesn’t feel nostalgic. The opening track, “Si Veo a Tu Mamá,” about running into an ex’s mom during the purgatory-ish period following a breakup, lays 808 boom-bass beneath a vintage-sounding keyboard interpolation of “The Girl From Ipanema.” The result is an earworm that evokes both an Atari game soundtrack and grocery store Muzak. Another hit from the album, “Safaera,” incorporates a tumbi sample from Missy Elliott’s “Get Ur Freak On” and the bass line from Bob Marley’s “Could You Be Loved.” His second album of 2020, Las Que No Iban a Salir, a compilation of outtakes released last May, is similarly layered. When it comes to sheer groundbreaking breadth, however, neither quite touches the third.

El Último Tour del Mundo has a few straightforward reggaeton tracks, including “La Noche de Anoche,” Bad Bunny’s steamy duet with Rosalía. (What was it like working with the Spanish singer? “Beautiful,” he said. “That was one of the songs that gave me more life in a collaboration. Like, we felt it. I loved the experience of working on a video with her. So, for real, it was very nice.”) The rest of the album blends so many genres that it almost comes across as a dare: Just try to categorize this. Its biggest single, “Dákiti,” is equal parts reggaeton and synth-y house. Other tracks fuse ’90s alt-rock elements with trap beats, or New Wave with rock-en-español. The album closes with “Cantares de Navidad,” a Christmas song recorded in the 1950s by Trio Vegabajeño, a group from Bad Bunny’s hometown. Another track samples the legendary Puerto Rican astrologer Walter Mercado. “I liked Walter’s intention to always give hope and messages of optimism,” Bad Bunny explained. “He was born on March 9, and I was born on March 10. We’re Pisces: emotional, sentimental, and sometimes difficult to understand.”

The Row sweater vest; Charvet shirt and socks; Adidas pants; Balenciaga sunglasses; Hermès tie; rings: (left hand) Marvin Douglas, (right hand) stylist’s own; Prada shoes.

Bad Bunny will be taking all this new music on the road in 2022. He recently announced a North American tour, his biggest to date. In the meantime, he has been keeping busy. His rivalry with the Miz culminated in a showdown at WrestleMania in mid-April. This was the realization of a childhood dream. (He used to watch wrestling with his dad, and one of his earliest music videos featured the WWE legend Ric Flair.) But the rigorous training schedule also turned out to be an excellent way of coping with pandemic anxieties. “It has been a good way to relieve stress,” he told me. “Focusing on something else, working more with my body, the mind, and doing something different. It couldn’t have been a better time.”

He has been dabbling in acting, too. He recently wrapped Bullet Train, an action film starring Brad Pitt. He can’t disclose many details about his role, except that the character is very different from him: “It’s about a boy who lost his family at a very young age. He dedicated his life to the streets, to be a murderer. So, an aggressive guy who has suffered a lot.” Working with Pitt was “very, very cool,” he added. “I was back there on the set, and I’d say, This can’t be true.” He will soon guest-star in Narcos: Mexico, playing Arturo “Kitty” Paez, a gang member with a sense of humor (“He likes to make jokes. He likes to have a little fun”). Later this year, he will have a role in American Sole, a comedy produced by Kevin Hart whose cast includes Pete Davidson and Offset. In addition to all this, he wrote a song for the Fast and the Furious franchise—“I have it ready,” he said. “We are just waiting for the moment to release it”—and designed a series of sneakers for Adidas. (Much like the glow-in-the-dark Crocs he lent his name and iconography to, they sold out immediately.)

Louis Vuitton Men’s jacket, shirt, skirt, hat, tie, and boots; rings: (right hand, from top) Vitaly, Jewels by Dunn, his own, (left hand, from left) stylist’s own, stylist’s own, Jewels by Dunn; stylist’s own earrings.

In the weeks before our interview, he’d been writing yet more music. “I have, like, a mechanical process that I call mecánico, and it’s the one that I like the least,” Bad Bunny explained. “And then there is the real process, the one with the muse, with the creativity, that comes on suddenly, when you weren’t expecting it. Your subconscious is talking to you about what you are feeling without you knowing, and it comes out, a lot of times, when I’m alone at night.” He continued: “I write sad songs at night. Happy songs I write during the day, after working out, after a fun day. And so I can adapt a lot when it’s time to write, but that’s the process I like the most—the one where, when I feel it, it comes out naturally in the moment, without even knowing where the lyrics are coming from. But they come.”

Louis Vuitton Men’s sweatshirt, shirt, skirt, and tie; Gentle Monster x Marine Serre sunglasses.

Grooming by Carola Gonzalez at Forward Artists; set design by Spencer Vrooman.

Produced by Alicia Zumback at Camp Productions; production manager: Chris Null; photographer’s producer: Rocket Caleshu; photo assistants: Lydon Frank Lettuce, Jake Nadrich; lighting assistant: Tyler Adams; retouching: Studio Private; fashion assistant: Lucy Gaston; set design assistant: Andrew Bond; production assistant: Rus Laich; tailor: Irina Tshartaryan at Susie’s Custom Design, Inc.; Covid compliance officer: Luke Lovell.

This story appears in W: Volume 3 2021, The Music Issue. Get the latest issue of W here.

This article was originally published on