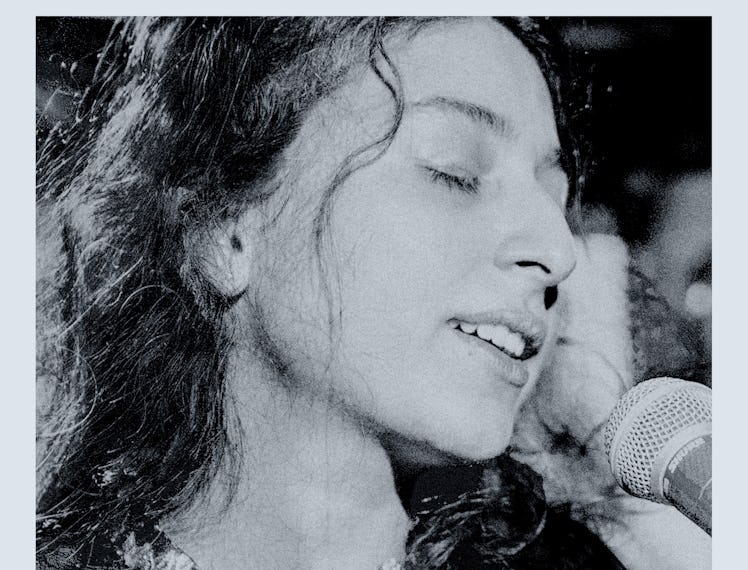

When Arooj Aftab was in high school, she taught herself to play guitar, recorded herself singing covers, and posted videos of her at-home performances on the Internet. From her bedroom in Lahore, Pakistan, Aftab sang Jeff Buckley’s ten-minute rendition of “Hallelujah” and local rock artist Aamir Zaki’s “Mera Pyar” (“My Love”), strumming her guitar and crooning in a soft, melodious voice. It was the late ‘90s, and YouTube didn’t yet exist—but the music scene in the Muslim-majority country flourished with the popularity of boy bands that synthesized traditional rhythms of the region with the alternative-cool of rock music. Aftab’s covers spread like wildfire online, rippling in e-mail threads and digital forums, and heralded the now-36-year-old Brooklyn-based artist’s calling as a singer and musician.

“This was a pre-social media era,” Aftab says over Zoom on a sunny winter afternoon from her home in Brooklyn. The singer’s video is turned off (“I’m the least fashionable right now,” she says), but her deep, tranquil voice radiates from the screen of my laptop, as sonorous when speaking as it is when singing. “There was no young woman singing freely [on the Internet]. It inspired a lot of people, and my role in all of it was to be a catalyst to the underground scene [in Pakistan], especially for women.”

The virality of Aftab’s covers sparked the ubiquity of bedroom pop in Pakistan, a DIY music movement in which young musicians who lack expensive recording equipment, a sophisticated studio set-up, and connections in the entertainment industry can record music from home and post it on Facebook, SoundCloud or YouTube. For women, who might face resistance from their families by openly performing music in a deeply conservative country, or who venture out less freely than men due to the dangers of sexual harassment and the unpredictability of local politics, the flexibility of social media has proven groundbreaking. Whether it’s Natasha Noorani’s strong pop vocals, Slowspin’s delicate lilting trill framed against atmospheric mixes, Hasan Raheem’s rich boy vibe, or even rap duo Young Stunners’ satirical reflections on city life, Arooj Aftab did it first—and those who came after her are still inspired by her approach to music.

The self-made success of Aftab's covers cemented her decision to pursue music not just as a career, but as the main purpose of her life. Aftab studied at Berklee College of Music in Boston, then moved to New York City in 2011, where she has been making music ever since, merging the sounds of jazz, electronica, and reggae with the folk tunes of her hometown—creating a unique, nearly peerless sound that is entirely her own. Her style is so one-of-a-kind, it’s caught the attention of former President Barack Obama (he included her song “Mohabbat” on his list of favorite tracks of 2021), and Caroline Polachek, for whom Aftab opened during a concert in New York City this year. Rock band The National even recommended her album on Bandcamp.

Today, Aftab has released three solo albums, won a student Academy Award for composing music in the short film Bittu, and received a Latin Grammy for providing backing vocals to Puerto Rican rapper Residente’s song “Antes Que El Mundo Se Acabe.” Aftab’s latest album, Vulture Prince, which released earlier this year, utilizes the ghazal, a form of devotional South Asian poetry set to music. On the record, she reinterprets the ecstatic arrangements of the mystical Sufi Muslims for a modern audience interested in a more intent and pared-down sound. Since then, Aftab has received two Grammy nominations in the wake of Vulture Prince’s meteoric rise, making history as the first Pakistani woman to be acknowledged by the Recording Academy.

“[I’m] really over the moon,” Aftab says of the nominations, one of which is in the Best New Artist category. “My collaborators and I, we worked really hard on Vulture Prince, and I’m proud of it as a body of work. It is an extreme surprise, but it’s also like, why the fuck not—it’s a great piece of music. It deserves accolades, it deserves a seat at the table, you know?”

The seven-track Vulture Prince represents the culmination of Aftab’s work, and draws inspiration from classical Urdu poetry, a language conceived in the royal courts of Indian Muslims in the 12th century, and which persists today as Pakistan’s national language. The majority of Aftab’s work is in Urdu, though she sometimes alternates between Urdu and English, as in the song “Last Night,” a composition of Persian poet Jalaluddin Rumi’s poem of the same name. “Last night, my beloved was like the moon/so beautiful,” she sings, as chords briskly start in the background, brilliantly contrasting the iridescent romance of Rumi’s poetry with the jazz and reggae ambience Aftab adopted in her musical practice while living in the American Northeast. “Urdu is such an emotive language, and in it, you can say so much by saying so little,” she says. “At some point, the music transcends, it goes past being from traditional roots and becomes a very personal thing. It’s what I experienced growing up in Pakistan, then in a very hardcore jazz curriculum in Boston, and then living in New York for years.”

“Last Night” is decidedly one of the more upbeat songs on the album. The rest of it is more somber, reflecting on unrequited love—as in the Grammy-nominated “Mohabbat” (“Love”), or the heartbreaking disappointments of life in “Inayat” (“Blessings”). The hushed pain that resonates through Vulture Prince is personal: Aftab lost her younger brother, Maher, and a close friend, Annie Ali Khan, in 2018 while she was recording the album. “Music is my mirror, it’s my river. Everything I’m experiencing, without a doubt, gets emotionally translated into the music I make,” Aftab says.

Aftab composed a poem Khan wrote for her in 2014 to record the track “Saans Lo” (“Breathe”). Khan had been a model, who starred in the music video of a song by famous Pakistani pop singer Shehzad Roy in the early 2000s, and then became a journalist, writing a book on female shrine worshipers that was posthumously published. She tragically took her own life at the age of 41 years old.

“One night, I was doing this thing which you really shouldn’t do: looking at old texts and e-mails and stuff. I found this poem she had written. And she was like, ‘You should compose this.’ I never did it [at the time]. And I was like, I’m going to put it in the record. That’s going to be my catharsis, my last goodbye,” Aftab says.

Much of Aftab’s music, after all, focuses on amplifying the voices of women who have been forgotten by history and otherwise sidelined and misunderstood by wider society. Her 2018 album Siren Islands used trance music to sonically convey the ethereal voices of the sirens of Greek legend—and an upcoming project promises to unearth the voice of Mah Laqa Bai Chanda, a courtesan and beautiful patron of the arts who lived in southern India in the eighteenth century, and served as a muse for iconic Urdu literature. Aftab wants to recreate her poems into songs.

“She has this whole diwan of poems, and no one has ever composed them,” Aftab says. “I think it’s worth it, because these icons, who are women, get written out of history all the time. And that doesn’t mean they’re not there. It’s up to us to find this shit and put it out.”