At the moment, Gen Z can’t seem to get enough of the aughts—just look at the overflow of TikTok videos dedicated to recreating Y2K fashion, or Vogue’s recent bold declaration that “the 2014 Tumblr girl is back” if you need examples. Look closer, though, and you’ll see that the prime of the “Tumblr girl” can actually be traced to 2013, and her muse was none other than Alexa Chung. (Twee, on the other hand, was embodied by Zooey Deschanel.) During that period, the English model was highly revered, with social media sites like Tumblr, specifically, hosting a voracious appetite for all things related to Chung, who served as a collective moodboard for a loyal cult following to obsess over her indie take on androgynous style.

From 2007 to 2017, Chung was admired for her polished wardrobe, envied by teenage girls everywhere for her former relationship with Arctic Monkeys frontman Alex Turner, and celebrated for hosting her very own MTV daytime talk show, It's On with Alexa Chung. (A credit to Chung’s tendency to remain ahead of the curve, the series was one of the first shows on TV to include tweets in the live program.) Though she appeared as an on-camera presenter in the early aughts, the MTV talk show was a pivotal moment, and soon, Chung was catapulted into the mainstream, where she would evolve into something so much bigger than your average television personality. In 2010, she inspired a Mulberry handbag while also putting brands like Madewell, AG Jeans, and Superga on the map. She had perfected the art of looking cool in every way, to the point where anyone and everyone thought they could also easily pull off wearing Barbour jackets with Hunter boots.

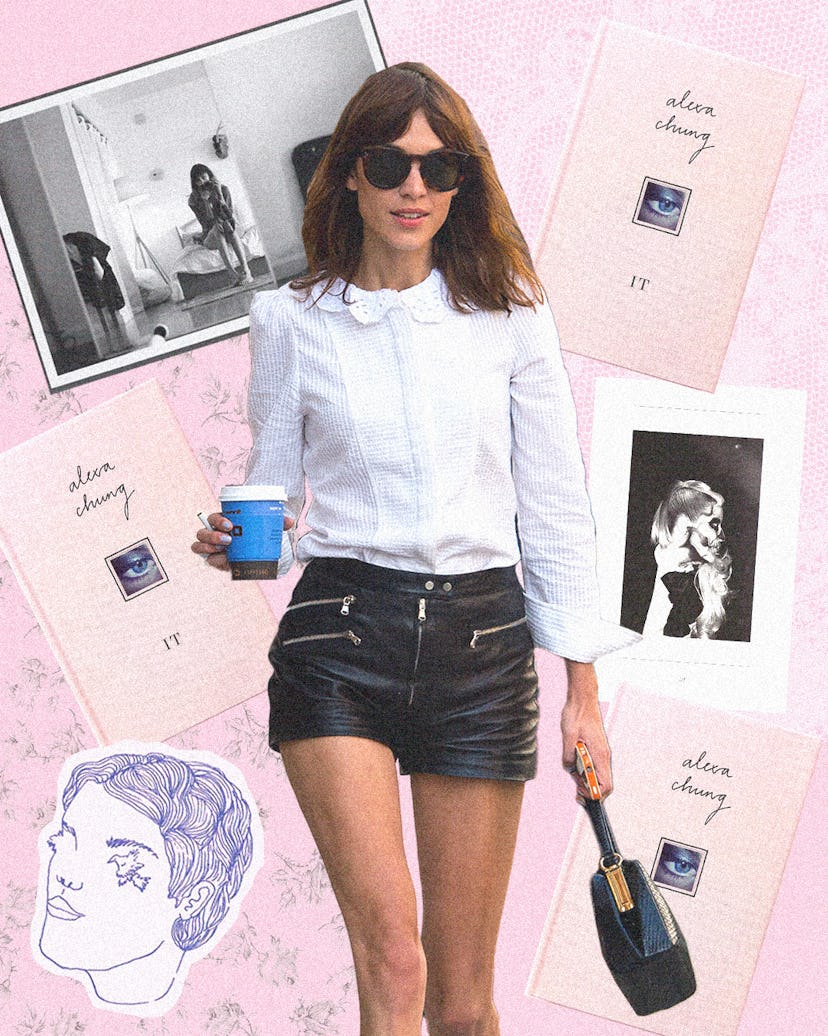

Chung was more than a global style icon, though: she was a proto-influencer, before we even had the terminology for this genre of celebrity. Her knack for making the most mundane things seem exclusive to her (like when she became a purveyor of “the boyfriend sweater”) is now a hallmark of influencer culture. Between the television hosting duties and editorial gigs for British Vogue, she was considered the ultimate It girl by many, but it was her debut book, It, that flung her to a new level of adoration, and became the status coffee table book of the era.

Last November, the writer Megan Hein named It as a piece of “ancient history” in a tweet. When she was a 14-year-old living in Ellicott City, Maryland, this was so much more than any regular coffee table book—It was like a bible. “There weren’t too many people that I could relate to in real life or look to for inspiration,” Hein recalls. “Getting that book and understanding more about [Chung] and the way she wrote it sounded like talking to a friend.” Hein didn’t expect her tweet to go viral, but the sentiment was obviously shared, earning her many features on TikTok.

“I was looking for haircut inspiration so I was flipping through [the book] trying to look for pictures of [Chung] specifically, but then I got to reading and I was like, ‘Wait, this is kind of amazing,’” she says. “I was so nostalgic! I used to bring this book everywhere with me.”

In 2013, It was seemingly everywhere—you couldn’t walk into an Urban Outfitters without seeing the hardcover strategically stacked on the front display table. Alayna Giovannitti, associate social media director at Urban Outfitters, remembers how excited the team was about the opportunity to interview Chung for a feature on the now-defunct blog about the book release. “I'm not kidding, in every UGC photo, [the book] was spotted somewhere in the background,” she says. “People would put their gold jewelry on something and take a picture of it for social media, I just wonder how many people [read] it or if they were just using ‘It’ as a prop... I forgot that it was even [Alexa Chung’s] book after a certain point because it was everywhere.”

Savannah Sicurella, a writer based in Atlanta, Georgia, fondly remembers begging her parents to buy her a signed copy of It for her 14th birthday. From Sicurella’s point of view, Chung had this effortless elusiveness, or what she describes as “that very high pinnacle of unattainable coolness.”

“She was like the perfect cocktail of everything that the public wanted,” Sicurella explains. “It's crazy to think of her ascending to that cult style-icon status pre-Instagram, pre-Twitter, only fueled by style bloggers, Teen Vogue streetwear pages, and Tumblr blogs. Is that even possible anymore?”

Critics, on the other hand, were not all fawning over It. The Guardian’s 2013 review described the book as a “stoned fashion student's end-of-term mood board,” writing it off as a “missed opportunity” for Chung to clap back at being praised as a symbol of “thinspiration” and address “the omnipresent negative facet of her success.” The writer even went so far as to label her as “an It girl for the kind of haters who like to pose as righteous.”

But the intention of It was to provide an “inside look at her fascinating world” through a collection of personal writings, drawings, and photographs. It was only meant to be a snapshot that reflected a fun moment in Chung’s life as a 29-year-old—the deepest it gets is an essay about heartbreak. “Honestly, it was as dumb as I wanted to have said that I've written a book before I was 30 so that was kind of the deadline in my mind. I was like ‘By hook or by crook, this will happen,’” Chung explains on a Zoom call from her home in London. “I wasn't like ‘I really feel it's my duty to educate the younger generation on how to wear a leather jacket.’ Everything was a lot more frivolous and silly because it was a more innocent time, but I think it speaks to that era that it was a fairly apolitical, sort of nonsense thing.”

While she didn’t pay much attention to the reviews at the time, Chung tells me she felt “intimidated” for being “analyzed as a writer.” She vividly remembers experiencing her first panic attack during the book launch while waiting at Liberty, her favorite shop in London. As she peeped out the window at a queue of girls wrapped around the block, the author began to feel extremely overwhelmed. “I hadn't imagined that there would actually be an audience for this, that they would actually queue up, and that people might want me to sign it,” she says.

Chung hasn’t looked at It since she published the book almost a decade ago. Make no mistake, she’s proud of the work and very fond of that period in her life, but there’s a certain level of embarrassment that comes from revisiting a past version of yourself. (Much to her English nature, she still finds it difficult to cheerlead her own accomplishments.) “I was trying to think about why I haven't been able to open it,” she says. “Because of the time when I wrote it and the emotional state I was in, I'm really worried that it feels to me like showing someone your knicker draw and being like, ‘Please come and look at my dirty laundry!’”

Now at the age of 38, Chung identifies as an “ancient grandma.” She recalls how the original pitch for It was a photography book, but she got talked into writing personal essays and vignettes to go alongside the images. If it wasn’t obvious, the title was a cheeky joke where she got the last laugh. Writing gigs served as critical opportunities for Chung to establish herself as a real authoritative figure with substance.

“I was always thrilled to do anything where I could have a voice because I started as a model which is obviously a mute role,” she explains. “Models today can be personalities, it's very much encouraged. Even people embracing diversity… When I started, they took [my surname] off the card and were like ‘Oh, we need you to be racially ambiguous so then anyone can hire you.’ I was never known as Alexa Chung, I always had to just be Alexa C.”

When It was released, projecting ideas onto celebrities and holding them to impossibly high standards was normal, but the expectation that celebrities be spokespeople for sociopolitical causes wasn’t as prevalent across social media as it is today. Chung’s rise coincides with the emergence of the Girlboss, but as Sicurella remembers it, “Alexa Chung never really rode that wave–she was never corny in the way that all of these [other] female empowerment leaders were.”

Giovannitti agrees, noting that Chung “represented a certain amount of humanity” before we realized how “toxic the Girlboss thing would become” as it evolved into such a huge part of personalities with the massive shift toward rise and grind culture. Upon further examination, one could say that Chung’s long reign of It girl-dom served as a precursor to the Girlboss era, marked by the 2014 publication of Sophia Amoruso’s GIRLBOSS. Popular at the same time, It and GIRLBOSS represented different approaches to “influencing” in the 2010s. But as Giovannitti points out, both pink books were, “a weird social media status symbol [on the Internet] that became ubiquitous.”

Now that the Girlboss has been banished to oblivion, what's next? The social media landscape is oversaturated with people that want to be famous, and being an influencer doesn't have the same amount of impact anymore. Even though she had a multi-faceted career, Hein argues that it was Chung’s lifestyle that was the most influential aspect of her online presence. “Nowadays, people want to be seen,” she says. “[Chung] just happened to be seen.”

The pivot toward social media, for Chung, felt like coming-of-age in a moment where it seemed like people with a presence could write their own rules if they were savvy enough. “It was a much more unguarded time because we weren't really sure how long our social media footprint would live,” Chung says. She remembers the awkwardness that came from answering interview questions about identifying as a feminist and how risky it felt to do an AG Jeans collection that featured a graphic T-shirt with a print of her wearing a shirt with the term back in 2015.

Now, she’s blown away by how openly women can talk about their menstrual cycles in public, a move that inspired her to use her own platform to raise awareness about endometriosis, a diagnosis that she formally revealed in 2019. But in conversation, Chung is adamant about the fact that she is not an authority on everything, observing how so many people conflate fame with being the right person to speak on social politics and the pressure that comes with it. “I'm really glad that there are leaders that have stepped up and feel comfortable being a mouthpiece,” she says, “But at the same time, I don't think everyone needs to.”

Since 2020, Martha Fearnley and Kaitlin Eleanor Gleason have been dissecting the “cultural, psychological, and political contributions” of it girls throughout history on their podcast IT GIRL THEORY. The only reason that they haven’t dedicated an episode to Chung is because there’s nothing to prove—everyone is already in agreement that she qualifies. “She's been called an It girl the most number of times in history; everyone is obsessed with referring to her as an It girl,” says Gleason. “We really did project a lot onto her in terms of [her being] the archetype of the interesting woman of Tumblr.”

Chung’s awareness of how to package her image set her apart from other contemporaries of that period, like Cory Kennedy, Lindsay Lohan, and Paris Hilton; while they were often spotted at the same parties, they occupied different ends of the spectrum. As one of the last It girls of the millennial generation, Chung smoothly transitioned us into a more digital existence. Gleason argues that Chung seemed to have a tighter grip on the ability to regulate their media narrative than most. “I think, fundamentally, people want to see women be broken by fame and then rehabilitation,” she explains. “Alexa Chung didn’t let us see any sort of fall from grace… She seemed to always be in control.”

Fearnley isn’t sure how else to describe the appeal other than an aspirational aura, but commends how Chung “made it a job to be a muse for the masses.” In contrast to the male gaze, Fearnley argues that she was a “celebrity designed for women.” Sometimes, she wonders if Chung is responsible for the “millennial corporate casual” trend before it got co-opted by the Girlboss movement. Fearnley adds, “She made herself into capital and that's powerful.”

Bound in a shade that is now recognized as millennial pink—but really just matched the sofa from her New York apartment at the time—and printed with a photograph of Chung’s sparkling eye in a peep hole (she liked the idea that she was “finally staring back at everyone else”), It served as a vehicle to further promote Chung’s monoculture of influences through an assortment of references. “I thought it was funny to do this more magazine style tone that had very short, elongated captions because I wanted it to be as much a visual diary as it was a written experience,” recalls Chung. “We wanted to kind of wink at the thing that I seemed to represent in that moment.”

Both Fearnley and Gleason agree that It is a perfect time capsule for what it was like to be actively online in 2013. As part of the MySpace generation, Chung was trying to emulate the experience with an “understanding that attention spans have shrunk down and that anything was possible,” she says. Flipping through the book now almost feels like scrolling through a Tumblr dashboard, which, as Hein points out, is very meta given the fact that there were also so many pictures of It on Tumblr.

If you ask Chung what she thinks about society today, she would say that it is post-cool, or “naff”—English slang for “not very cool.” The recent conflation of indie sleaze and twee in the “Tumblr sandwich” is a good example of how style, according to Chung, is now “so easy to research that people have co-opted the look” without fully understanding the references. “That kind of pillaging and borrowing has meant that you can put the costume on, but you don’t have to have done your homework,” she says.

In a 2016 interview with W, Chung claimed that she had “grown to appreciate” the It girl title. She now confesses that she gets a bit cagey when people mistakenly call her an influencer, claiming that she “didn't choose to be famous, which is different.” The comparison also reminds her of being called an It girl, and how no one could comprehend what her job was because she was doing so many things at once. Chung recalls how the U.K. press was hyper focused on this, constantly leveling her with the nagging question, “What does she even do?”

As the years have passed, Chung has more openly aired some of her grievances with the It girl label which previously caused some distress due to flawed projections based on her public persona. “I was so defensive and I hated it so much because I felt like it was reductive when all I ever did was work pretty hard at things that I felt I was really professional about,” she tells me from the comfort of her living room. “The connotation of It girl, to me at the time in its older iteration, was ‘a socialite who'd inherited money and did nothing for a living.’ I had not come from money, I made my own way in the world, and I found it a bummer.”

Chung laughs while talking about the ridiculousness of a photoshoot she had in December and how she compartmentalizes the many hats that she wears in real time. “They still don't really want all of it,” she grins. “Different people want different bits, you can't have all the things.” Longtime fans can rest assured that Chung isn’t plotting a TikTok takeover anytime soon, but she does admire how today’s content creators can be “masterful within something that's seen as common.” (She especially likes the idea of “taking something that's meant to be a flippant medium and try to make it look really high class,” like her YouTube channel.)

She also points out how the It girl has a shelf life and while she’s not sure when exactly one ages out of it, she firmly believes that she has. “I'm definitely at an age where I've begun to start reflecting on what's happened to me and acknowledging that actually starting full adult work at 15 is a really fucked thing to do,” Chung says. “I’m just trying to be a bit nicer to myself.”

These days, Chung is mostly preoccupied with outfitting her new townhouse in London with vintage furnishings, indulging in fantasies of “a more quiet offline reality,” and designing timeless collections for ALEXACHUNG, the label she started in 2017. She is open to the idea of writing a memoir of sorts someday, but don’t hold her to it. As she so bluntly states, “I've still got like over half my life left to live and we're already reminiscing about the first version of it.”